From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 2000). — J.R.

Requiem for a Dream

**

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Hubert Selby Jr. and Aronofsky

With Ellen Burstyn, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, Marlon Wayans, Christopher McDonald, and Louise Lasser.

Darren Aronofsky’s first feature, Pi (1998), had more style than substance — or perhaps it’s just that the only thing I now remember with much clarity is its razzle-dazzle style. The black-and-white cinematography and the jazzy editing were pretty attractive in a disposable sort of way, though critic Bill Boisvert had a point when he suggested in these pages that the attitude of this metaphysical thriller was “profoundly anti-intellectual,” rightly adding that this was “true of most indie genius films.” (He may have been more right than he realized. His second example was the 1997 Good Will Hunting, directed by Gus Van Sant, who’s been offering us nothing but anti-intellectual holiday releases about geniuses ever since — with Alfred Hitchcock rather than Norman Bates as the prodigy in the 1998 Psycho remake and Robert Brown taking the equivalent role in Finding Forrester, which opens on Christmas day.)

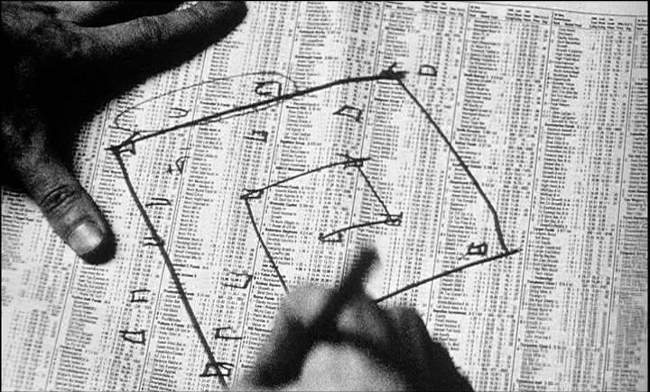

When I belatedly caught up with Aronofsky’s second feature, Requiem for a Dream, it was with the hope of seeing something more than just fancy style. And for the first half of the movie I wasn’t disappointed, because the conceit underlying this film’s show-offy style is more provocative and less conventionally reassuring. Most of the movie draws parallels between Sara Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn) — a Coney Island widow and TV junkie excited by the prospect of appearing on a game show, gobbling amphetamines of various colors four times daily in an attempt to lose enough weight to fit into her favorite red dress — and her son Harry (Jared Leto), a heroin addict with similarly addled dreams about striking it rich as a drug dealer while his arm turns into a relief map of an increasingly deep purple. Some of these parallels are suggested through lightning-sharp juxtapositions (executed by Jim Jarmusch’s editor, Jay Rabinowitz), and others are explored through split-screen effects — Aronofsky always seems happiest when he’s juggling at least a couple of things at once.

In addition to the simple stylistic contrasts between Sara’s uppers and Harry’s downers, the movie reveals contrasts between Sara’s neighbors and Harry’s two main companions, a new girlfriend named Marion (Jennifer Connelly) and Tyrone (Marlon Wayans), his business partner and best friend. And there’s a warm and touching relationship between mother and son, who display different versions of the same charm and have comparable reserves of protective concern for each another. Better yet is the poetic notion that these two characters suffer from two forms of the same malady — a point expressed directly by a recurring montage pattern of coffee chugging, coke snorting, joint rolling and toking, pill popping, and vein opening, all underlined by aggressive sound editing that harks back to the compulsive repetitive passage of crisply cut daily rituals in Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz. Both characters, one gradually comes to believe, are driven by the same national mythology about what success means in an aimlessly drifting existence; both their dreams quickly turn into horrific nightmares, which represent only the flip side of the desperate optimism that infects their lives.

As a metaphysical construction, this evokes the mood of some voters before and after the recent presidential election — euphoria turning into nightmare once it became clear that the whole game was fixed or illusory or at the very least highly precarious. Yet it’s hard not to view the postelection progress toward enlightenment as a worst-case scenario momentarily evolving into a best-case scenario — if you can resist the partisan and adolescent name-calling that’s overtaken both parties and can see that the process is only confirming how few meaningful choices any of us had in the first place. Of course the ideologically addicted persist in watching the developments as if they were part of a sports event in which the terms winners and losers remain meaningful (overlooking that the winner may turn out to be as hated, as mistrusted, and as ineffectual as the loser) — just as Sara goes on dreaming of her mythical TV appearance and Harry continues banking on his ultimate score.

Sara’s speed-induced fantasies that she’s being barked at by her refrigerator, which threatens to eat her alive, and that she’s being serenaded by the rhythmic chants of a menacing TV studio audience are rather inspired inventions. Harry’s soporific fantasies, unlike his grotesquely deteriorating arm, tend to be less memorable, perhaps because Aronofsky’s style tends less toward lyrical drift and more toward sped-up motion, even when cataloging the listless activities of a junkie. The greater effectiveness of Sara’s fantasies may also be a tribute to Burstyn’s gifts in tailoring much of her performance to expressionist designs, at least until the script literalizes this process by virtually turning her into stone.

Unfortunately, once Requiem for a Dream accumulates all this elaborate and suggestive paraphernalia, it plummets in an inexorable, almost mechanical spiral. I’m guessing that this is a consequence of the limitations of Hubert Selby Jr.’s source novel, which I haven’t had the heart to read. I did read one section of his Last Exit to Brooklyn, the notorious “Tralala” chapter, not long after it was published in the 60s; it’s an account of a cruel and sadistic teenage hooker that culminates in her being gang-raped, tortured, mutilated, and then possibly killed, all in a single sentence that extends over about four pages. I haven’t wanted to read anything else by Selby since, and now that I’ve seen this adaptation, which he cowrote, of his 1978 novel, I’m inclined to wonder if he might be a one-trick pony — though I don’t have enough morbid curiosity to check it out.

In any event, the final stretches of this story reveal the same pile-driver strategy as “Tralala,” in which heaps of abuse and injury are shoveled onto the characters, destroying our capacity to respond in any way except flinching. Oddly enough, this strategy functions much as the formalism of Pi did — we’re plainly meant to be impressed, though it’s not clear about what or why. In both cases, character development — indeed, narrative development of any kind beyond the most obvious — is obliterated for the sake of stylistic flourishes. Whether these flourishes belong more to Selby or Aronofsky doesn’t really matter — they can split the difference for all I care. I’d rather be back in the first half of this movie, where the flourishes of both artists still mean something.