From the October 6, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Seven

*** (A must-see)

Directed by David Fincher

Written by Andrew Kevin Walker

With Morgan Freeman, Brad Pitt, Gwyneth Paltrow, Richard Roundtree, R. Lee Ermey, John McGinley, Julie Araskog, Mark Boone Junior, and Kevin Spacey.

Since when have designer vomit, mannerist rot, and other chic signifiers of gloom, doom, and decline become such comforting mainstays of movies? I’m thinking not only about Hollywood but about Western cinema generally. What brings on all the driving, dirty rain in Satantango (Bela Tarr’s seven-hour Hungarian black comedy, which showed at last year’s Chicago International Film Festival) as well as in Seven, a stylish and affecting (albeit gory) metaphysical serial-killer movie? The facile solution would be to trace the gloom back to Blade Runner, film noir, maybe even to Prague school surrealism, though this would omit the Calvinist/expressionist vision of urban filth and the post-Vietnam psychopathology of Taxi Driver. In point of fact, it’s much more important to figure out the reasons for the strange allure of this grim sensibility than to worry pedantically about where it came from.

I’d ascribe at least part of this taste to the current inability to believe in or try to effect political change — a form of paralysis that in America is related to an incapacity to accept that we’re no longer number one. (It’s a pity we can’t learn from the experience of the British, who had to cope with a similar problem some time ago; acceptance of our limitations might actually liberate us.) Within this context of denial, trash, decay, and apocalypse become very attractive — a kind of spiritual heroin. If everything is so terminally and beautifully hopeless — if evil is omnipresent and triumphant (as Seven so potently maintains) and mankind is incapable of climbing out of the primordial slime — then we’re let off the hook: we don’t need to assess who and where we are, what we should do, who’s running the show and why. The very capacity to observe violence and torture without flinching is often made to seem an index of world-weary sophistication and maturity — revealing a hip understanding of how rotten our world is and why we’re right to do as little as possible to change it.

Such films legitimize our passivity as consumers and as citizens, and we can soak in our pessimism as if it were a warm bath, fondle our sour apathy as if it were a form of higher wisdom. To call our current state the decline of civilization sounds a lot grander than to see it as the erosion of a few Western power bases (whose erosion might actually benefit the world at large) or as the result of a decline in government services. And we’re still so sunk in cold war terminology that we can’t see that the collapse of communism — or what was erroneously called communism by both sides of the cold war — doesn’t necessarily mean that Marx was wrong or that we were right. (To many smaller countries, the similarities between Russia and the United States during and after the cold war are more striking than the differences.) The long-term absence of new thinking in commercial filmmaking — unless one calls new strategies for recycling movies and TV “new thinking” — above all reflects a rigid business policy to exploit existing markets to the limit rather than develop any new ones, which would require risk and creativity. One of those overworked genres sees urban blight as the occasion for a detached euphoria linked to metaphysical fatalism. The trick is to make it feel like a fresh idea, a trick that Seven pulls off remarkably well.

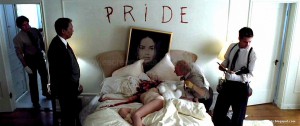

Some reviewers have been calling the film hackneyed and implausible. I suppose they’re right about the plot, but their observations ignore what makes the movie a noteworthy achievement, which is almost entirely a matter of stylistic freshness and conviction, the special look and feel of certain actors and sets. (Morgan Freeman as a weary moral witness, for example, a burned-out police detective on the verge of retirement who suffers from insomnia. Or the cavernous gutted urban apartment with hundreds of air fresheners hanging from the high ceiling and a tortured, still-breathing human skeleton under a bedcover.) Such criticism doesn’t take into account the excitement of the opening credits sequence — a jerky, grainy, scratchy bit of experimental film that looks like prime Stan Brakhage, one of the most exhilarating stretches I’ve seen in a Hollywood picture all year. Certainly the press book didn’t lead me to expect anything special. Director David Fincher is best known for music videos (for Madonna and the Rolling Stones), TV commercials, and Alien3 (where a taste for sordid surroundings and religious fanaticism is also apparent). And the first-time screenwriter, Andrew Kevin Walker, wrote the script while working as either a floor manager or a cashier (depending on which page of the press book you’re reading) at Tower Records in New York.

Seven begins with Detective Somerset (Freeman) methodically dressing in his drab bachelor flat in some nameless, generic, wasted city and going off to examine the scene of a bloody multiple homicide unrelated in terms of plot to anything else in the movie. We see him getting chewed out for wondering whether the dead child on the scene actually witnessed a parent’s death before he was killed himself: a callous, irritable colleague tartly tells him it’s irrelevant to the investigation. Then Somerset meets Detective Mills (Brad Pitt), a rookie who’s asked to be trained as his replacement, a fact Somerset is rather testy about. Then come the credits, which introduce us to some of the belongings and activities of the not-yet-introduced serial killer — or are they the materials and activities of the police who are investigating the killer much later in the picture? Our uncertainty about this seems pivotal rather than incidental: the links between art making, murder, and murder investigation are what matter. We glimpse photographs, notebooks containing obsessively small and neat writing (recalling the notebooks of Charles Crumb in Crumb), film being spliced, something being sewed. Then the first of seven days — “Monday” — appears at the bottom of screen left while Somerset and Mills are examining the site of what proves to be one in a series of exceptionally gory, savage killings of innocents based on the seven deadly sins.

The seven-day, seven-sin construction is only part of this movie’s high-concept packaging, which also entails similar production designs at many of the sites investigated by the detectives — dank, clammy apartments belonging to either the victims or the killer himself. (Irrationally, most of these are investigated by flashlight even though it’s daytime — no one ever bothers to flick on a light.) As in Blade Runner, where the heavy rainfall is equally continuous, a sense of endless night pervades even daylight hours; rotting interiors and peeling walls seem part and parcel of the evil activities and are tied (as in Taxi Driver) to Calvinist outrage about the foulness of contemporary city life.

Part of the movie’s high-concept statement about the modern world — which ultimately may be just an excuse for its high mannerist style — is a detailed generational comparison between Somerset and Mills in terms of morality, maturity, temperament, family ties, even education (Mills bones up on Dante, Chaucer, and Milton by using college outlines while Somerset prefers the originals). There are also many implied comparisons between this movie and The Silence of the Lambs, underlined by an exemplary contrast: Seven refuses to exploit its psycho killer for cheap laughs or blind hero worship. Less happily, it does harp, as Silence of the Lambs did, on its villain’s superhuman dedication and efficiency, clearly aiming for a sense of spooky hyperbole comparable to the virtual halo manufactured for Hannibal Lecter. (The killer in Seven has accumulated no less than 2,000 250-page notebooks filled with his writing, he spends an entire year torturing one victim without killing him, he even causes the same victim to chew off his own tongue — recalling Lecter’s supernatural capacity to induce a prisoner in an adjacent cell to swallow his tongue.)

Apocalyptic jive is substituted for real-life horrors, which are felt to be both insufficient and irrelevant to the full-fledged hell incarnate Seven wants to convey. Social awareness gives way to metaphysics, and the movie’s touching, old-fashioned faith in the power of good to reassert itself (”I’ll be around,” says Somerset) runs neck and neck with the fashionable premise that martyred serial killers remain our truest holy men. In other words, for all its power, Seven remains first and last a stylistic exercise, and its message, like most messages nowadays, is to remain exactly where we are.