From the Chicago Reader (September 4, 1998). — J.R.

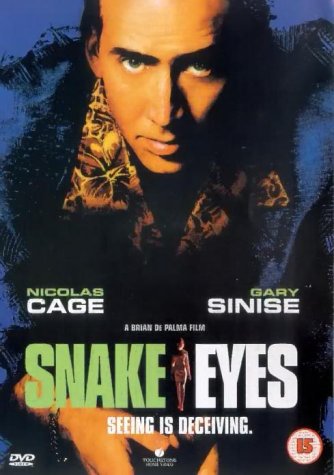

Snake Eyes

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Brian De Palma

Written by David Koepp and De Palma

With Nicolas Cage, Gary Sinise, John Heard, Carla Gugino, Stan Shaw, Kevin Dunn, Michael Rispoli, Joel Fabiani, and Luis Guzman.

For me, part of the fun of Snake Eyes is the genuine satisfaction of seeing Brian De Palma finally arriving at his own level. Whatever the merits of his imitations and appropriations — of 50s Hitchcock in Dressed to Kill, Obsession, and Body Double, 60s Antonioni in Blow Out, and 30s Hawks in Scarface — and his inflations of TV standbys (The Untouchables, Mission: Impossible), they’ve always suggested he was riding into town on somebody else’s horse. Now, however, he seems more apt to make the 90s equivalents of B movies: such films as Raising Cain, Carlito’s Way, and Snake Eyes are generic stylistic exercises that reveal he’s digested his sources rather than simply devoured and regurgitated them. Though he remains too much of a mannerist to approximate the modest craft of Roy Ward Baker in Don’t Bother to Knock or Richard Fleischer in The Narrow Margin –– thrillers of 1952 that in their adept use of real time and limited settings suggest parallels withSnake Eyes — De Palma’s technique seems more focused for a change. He finally seems to be making his own kind of movie, not a trashy reduction or glitzy expansion of someone else’s.

Several reviewers have argued that the extended Steadicam shot that opens Snake Eyes is the only reason for seeing the picture, but I disagree: formally and thematically it sets up the four flashbacks covering the same patch of time. And you can’t fully appreciate the Steadicam shot without the complementary addenda, which progressively solve the puzzle of what actually happened. In that shot, a corrupt cop named Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) enters an Atlantic City casino-hotel complex to attend a heavyweight boxing match, accepting bribes and placing bets en route to the arena while responding to calls on his cell phone from his mistress and his wife. At the arena he meets an old friend, navy commander Kevin Dunne (Gary Sinise), now working for the Defense Department and accompanying the defense secretary — who’s assassinated at the end of the shot. Before that, Dunne follows a suspicious redhead out of the arena, and a mysterious blond (Carla Gugino) takes his seat, in between Santoro and the defense secretary. When the bullets start flying, the blond — Julia Costello — gets hit in the shoulder, then loses her glasses and wig before disappearing into the panicky mob of fleeing spectators.

The sequence is every bit as show-offy as it’s designed to be — an obvious sequel to the five-minute showpiece in The Bonfire of the Vanities, which was itself intended to top a Steadicam sequence in Scorsese’s GoodFellas. But what I mainly like about it is what it strategically omits — including the fight itself — which the four flashbacks provide. Santoro, a glib crook and obnoxious glad-hander, is at the center of this opening shot, designed to establish an entire moral universe; because the picture never strays from the Atlantic City complex (except for a brief TV news report toward the end), we never even glimpse his wife or mistress. The only problem is that what constitutes an entire universe in any De Palma film is closer to a floor plan than a moral vision — that’s how his style works and that’s why it can become limited.

Putting together the puzzle of what happened during the opening sequence from four later accounts — those of the heavyweight champ, Dunne, Costello, and Santoro’s own revised version — is the main course in Snake Eyes. Everything else — including the establishment of character and plot — is a kind of side dish. Although De Palma doesn’t always stick rigorously to each separate viewpoint, there’s an undeniable finesse in the way he parcels out the exposition in increments, showing a little more each time of what we failed to grasp in previous versions — a triumph of both engineering and encoding that’s also partly a matter of dramaturgy. Indeed, Cage’s abrasively goony performance, a self-conscious tour de force, represents a strategic distraction from the events of the opening sequence. “Appearances are deceptive” is an axiom of De Palma’s cinema — not so much because it’s his vision of life, one suspects, but because it’s an obsessive formula or pretext for making his kind of movie.

So the narrative pleasures of Snake Eyes are essentially those of solving a puzzle. The hero’s moral regeneration — accomplished in less than two hours — is supposed to lend weight to the proceedings, but given De Palma’s floor-plan approach, the moral issues never seem very real. The skeletal plot revolves around the fact that Julia, a Defense Department employee, has discovered that the reports on a particular missile test have been doctored, and she’s arranged to meet the defense secretary incognito (hence the wig) at the boxing match to report her findings.

The implausibility of such a meeting is glaring. But rather than attempt to rationalize it, De Palma apparently hopes we won’t notice — and it’s pretty clear that, if we’re on his giddy stylistic wavelength, we won’t care. (Paying only rudimentary attention to such matters is commonplace these days anyway, not only in Hollywood but in mainstream news. Reports on Clinton’s retaliation against the East African terrorist bombings, for example, routinely assumed the public wouldn’t be even remotely curious about what motivated the bombings in the first place.) Somewhere over the course of Santoro’s investigation, he’s supposed to be so moved by Julia’s selfless quest for justice, or by the size of her breasts, or by some combination thereof, that he risks getting beaten to death to save her life. But Julia’s sincerity is awkwardly and perfunctorily sketched in — we’re mainly asked to focus on her breasts, which De Palma is much more comfortable depicting: an extended overhead pan across several adjacent hotel rooms, one of his best grandstanding moves, climaxes with an aerial view of those protuberances as she’s cleaning off blood at a bathroom sink.

De Palma subordinates various questions of plot — what motivates a Pentagon conspiracy, a Palestinian assassin, a heavyweight champ who takes a dive, a newscaster who bribes Santoro, an idealistic Defense Department worker, and a crooked cop who goes straight — to the body of a curvy actress. Consequently, it doesn’t appear to be her fault that her performance seems phoned in. By the same token, whenever De Palma wants to remind us of Santoro’s moral corruption, he reinserts a blood-soaked $100 bill; thanks to the example already provided by Bill Duke’s Deep Cover, he can trot out that emblem as a kind of shorthand rather than worry about character development.

Central to De Palma’s modus operandi is a jokey remoteness from his characters and their humanity. (He even draws some of his characters’ names from his cast and crew: “Kevin Dunn” is the name of the actor who plays the newscaster, and I spotted at least a couple of Santoros among the crew members.) Some critics, following Pauline Kael’s lead, have tried to valorize this stance, saying that De Palma’s exaltation of the trash aesthetic approaches the transcendental.

Similarly, De Palma tends to spread music on like heavy paint, trying to cover up the emotional gaps in his stylistic exercises. The result is that the music generally registers as facetious and unearned — a kind of hypocritical sop to the audience. In the case of Obsession, my favorite of De Palma’s early thrillers, Bernard Herrmann’s score was so pervasive and so affecting that in some respects it superseded Paul Schrader’s script and De Palma’s mise en scène. In fact the music literally superseded the script in the sense that Herrmann agreed to score the film only if De Palma deleted Schrader’s entire third act: in effect the music took over the roles of story and mise en scène, which merely accompanied the score. But De Palma’s music more often operates, as it does in Snake Eyes, as a cue to the audience that events seen remotely and voyeuristically are to be given metaphysical and moral weight. Here Ryuichi Sakamoto — the gifted composer of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence and The Last Emperor — supplies the music, which strikes me as phony and inappropriate throughout, as if De Palma were trying to import a sense of gravity through the back door.

Sooner or later, practically every De Palma movie turns into a Punch-and-Judy show. Santoro is a grotesque from the beginning, but when he gets brutally beaten toward the end of the film, his features swell to bloated Punch-like proportions, as if to literalize his resemblance to a puppet. In every scene Dunne has bags under his eyes that look like they were drawn by Chester Gould or Milton Caniff, and Julia, as I’ve already suggested, is framed more like a sex toy than a human being: she enters the movie ass first, and her breasts are invariably shot from various angles like cantilevered balconies. Especially characteristic of De Palma is the courtly decision to turn her into a would-be hooker, as she approaches a creepy hotel guest hoping to find a safe haven; if she’s not quite as pliant as a Playboy bunny, it isn’t for lack of intention on De Palma’s part.

It’s easier for me to accept caricatural distortions of this kind in the work of Sergei Eisenstein or Stanley Kubrick because, whatever their cruelty, at least there’s a master intelligence behind it commensurate with the mockery. De Palma’s sensibility is wormier: his less heroic cartoonish instincts make his films seem the revenge of the nerds. But this is the register where he seems most at home, plotting his camera moves like a lonely boy in a basement. I find a closer fit between De Palma’s aspirations and his achievements in Snake Eyes than I do in the soul-searching, grandiose Casualties of War — which suggests that the filmmaker’s cynicism, his mannerist cartooning, and even his formal brilliance are far more debilitating when he makes an actual investment in the real world.