From Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983). Due to the length of this, I’ll be posting it in four installments. — J.R.

Tenants of the house,

Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

T.S. Eliot, Gerontion

Preface: When I was approached last year about inaugurating a series of volumes surveying recent avant-garde film, I immediately started to wonder about how this could be done. Having lived nearly eight years in Paris and London and about as long in New York, I’ve had several opportunities to note the relative degree of information flow between these and other centers of avant-garde film activity, and the growing isolation of New York from these other centers made my own fixed vantage point less than ideal in some ways. When a colleague told me that Jonas Mekas had recently said that it was no longer possible to know what was happening in experimental film as a whole, a bell of recognition rang in my head, and I knew at once that Mekas was the only available oracle l could turn to. The Lithuanian patron saint of the American avant-garde film, now 60, has been an American filmmaker for at least half of his life, and a chronicler of the avant-garde film in New York — mainly in The Village Voice and (more briefly) Soho News — for at least 15 years. If he no longer knew with confidence where we were, a consideration of the nature of the very problem of our ignorance was clearly in order.

Out of this need and curiosity, the two following conversations took shape, with Mekas’s kind consent, at the temporary headquarters of Anthology Film Archives on Broadway in lower Manhattan, in late July and early November 1982. Robert Haller, executive director of Anthology, was present at both discussions, and some of his remarks are also included.

The second dialogue, longer and somewhat more polemical than the first, occurred during a two-week season at the Public Theater devoted to Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet and filmmakers they admire (about two dozen films in all) that l was involved in curating at the time, and which became a logical reference point for part of our discussion. The results have been edited by Mekas as well as myself.

I.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: If someone were writing a survey of recent avant-garde film 10 or 20 years ago, he’d have a much easier task. Things were much more centralized then. If someone came to New York from, say, Kansas with an avant-garde film and he or she wanted it to be shown, that person would have gone to see you, probably.

JONAS MEKAS: Yes, between about 1960 and 1970. Before that, between 1950 and 1960, they went to see Amos Vogel or the Museum of Modern Art. In a few other big cities, like San Francisco, you could count on one place where you could go.

JR: But if someone came from Kansas with an avant-garde film today, he or she would be likelier to search out an institution, not an individual. And the person in charge at the institution might think, ”Do I like this?” But he or she would be just as likely to think, “Would the audience for the Collective for Living Cinema go for this?“ “Would the audience for Film Forum like this?”

JM: Today, New York is split into a dozen showcases. Why did these different showcases develop? Because, beginning with the Seventies, there were no longer 20 or 30 filmmakers to deal with, but literally thousands, making thousands of films. No one showcase could deal with that; so different showcases developed with preferences for different filmmakers. Actually, some of the showcases were started by filmmakers who felt excluded from other showcases. And, of course, filmgoing people as well as filmmakers became familiar with the preferences of the different showcases. Like somebody who is making abstract, personal films wouldn’t necessarily go to see Karen Cooper at Film Forum — unless they were cutely animated.

The field is too big now; no one can cover it all. Amos Vogel could cover all the varieties of avant-garde, experimental, and documentary. In the Sixties, the Filmmakers’ Cinematheque was already neglecting a lot of documentaries. Today, it’s impossible for any single showcase to show everything–unless you had three or four different programs every day. It’s not only that you have to catch up so constantly; you also have to give some background and show what went before, which is harder and harder. That’s why the Museum of Modern Art introduced their series “What’s Happening?”, to show the documentaries that no one was showing. And of course the feminist groups also have a purpose — to cover a certain area more in depth than any other. At Anthology the direction became more academically avant-garde because we felt that that part was neglected. We felt that once a film is shown at any of the showcases — no matter how good the film was, it had no chance of being reseen. Until just a few years ago it was mainly just new work that the showcases were interested in.

There are certain historical necessities that determine these developments: the volume of the production, the number of different directions in cinema, the size of audiences. Before, the audiences could all fit into one theater; now, if you put all the audiences together, they make big numbers, even for the independent films.

JR: What I find disturbing about this is how everything has become consumer-oriented and service-oriented. Consequently, there isn’t much of a sense of mystery about the avant-garde anymore: people aren’t curious about what they can’t see the way that they used to be.

JM: I wouldn’t say consumer-oriented. Millennium, for example, in the first place serves its own members, then serves all the others, so that it’s a semi-closed group. What do you mean by consumer-oriented–that it brings money? Millennium programs don’t make money.

JR: I mean much more the kind of money and attitudes that come from outside funding. I’m thinking that the success of certain points of view become institutionalized, that certain categories of films now pre-exist in people’s minds.

I’m also thinking of the differences between film magazines now and then. In Film Culture in the Sixties — compared to what you’d find in Millennium Film Journal or October now — there was an amazing range of people coexisting, a real pluralism. In one issue — Winter 1962/63 — it’s actually possible to see Sarris, Farber, Kael, Markopoulos, Weinberg, Smith, and Stern, all cheek by jowl.

JM: Yes, that was a classical period.

JR: What seems so depressing is how relatively little opportunity there is now for exchange and cross-fertilization and people listening to other ideas.

JM: No, each one is interested only in their own thing and there isn’t much variety, no.

JR: So if this same filmmaker from Kansas had to go to a film magazine today, he or she might have to choose one at the exclusion of another. It’s all feudal strongholds now; one can no longer introduce a film into a single community.

JM: The only thing is, I don’t know whether this is a negative or positive thing. What has developed is the phenomenon of the regional art centers. There are one or two hundred of these. And they very often try to show examples of all the varieties of film — some very new and “emerging” filmmakers, some classical avant-garde, some old Hollywood and some new European work. Some of them import films directly from Germany, or France, and other countries. You can see European and South American films in Houston at the Fine Arts Museum today that you can’t see in New York, for instance. Without these regional art centers, we would miss a lot of the European avant-garde. They come only because they have engagements at six or eight places and travel from one to the other. So while the New York and San Francisco showcases may be restricted to single directions, across the country that is not true–unless some center is run by some kind of fanatic of one kind of film.

JR: Well, you would certainly have a better notion than me of how much Americans are exposed on a national level to European avant-garde. But it seems to me that in a New York context, the situation of the European avant-garde is vastly inferior to what it once was.

JM: For the last five or six years there’s been a drop, that is true. Not that the European avant-garde is necessarily all that active. The Italian avant-garde died out. The British and German avant-gardes slowed down, relaxed. Only the French avant-garde is still active. But we don’t see any of it.

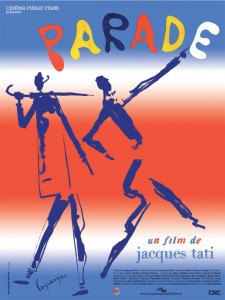

IR: One thing I want to do in my book is include certain films that, in one sense, are avant-garde precisely because they’re overlooked and ignored. For instance, I know of very few Americans who know about even the existence of Jacques Tati’s last feature, Parade, a circus film made in video.

JM: l didn’t know he made a film in video! But not knowing that a certain film exists doesn’t necessarily make that film avant-garde.

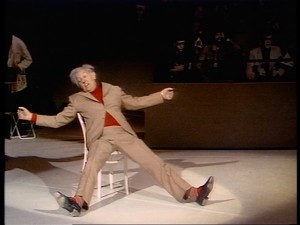

JR: True enough. Although sometimes it’s tempting to give preference to actual films over categories, regardless of the academic havoc this might create–there are so many homeless films of interest floating around, and so many standard avant-garde films of no interest whatsoever. I’ve seen Parade in both Paris and London; Tati made it in 1973. It was shot in video and transferred to 35mm film–an earlier version of the technique used on the Richard Pryor concert films. It’s an experimental film not only in that respect, but also in its attitude towards the spectator. A lot of the film consists of a circus show that includes many of Tati’s famous mime routines from his music hall days, but the audience consists of both real and artificial (i.e., flat and painted) spectators, and the camera is often positioned in such a way that this audience becomes just as prominent as the performers. Then there’s an epilogue when a little girl steps down onto the stage after all the performers have left and plays with all the props that are left behind. Jean-Marie Straub has said that what’s exciting about the film is that it’s about all the degrees of “nervous flux — beginning with the child which cannot yet make a gesture, who cannot yet coordinate her hand with her brain, and going up to the most accomplished acrobats”.

Parade, of course, represents only one example of an important work that is almost totally unknown in this country. Even when certain things get shown here, they often remain unknown. For instance, I just spoke to a graduate student who’s taking a summer course in Rivette, Rohmer, and Chabrol and asked his teacher about Rivette’s 1980 feature Merry-Go-Round — which he’d seen at the Museum of Modern Art in February 1980–only to discover that his teacher knew nothing about the film’s existence!