From Sight and Sound (October 1992). –- J.R.

Most of the American press has been all too happy to declare the new version of Orson Welles’ Othello as “expertly restored”, as Vincent Canby put it in the New York Times. But restored from what and to what? Even rudimentary information about the film’s original form is not easy to come by in the U.S., where 0thello brought in only $40,000 on its belated first release in 1955 and has been screened only sporadically since. Mutatis mutandis, the acclaim that has greeted the restoration recalls the unqualified press endorsements of Francis Coppola’s presentation of Abel Gance’s ‘complete’ Napoléon at Radio City Music Hall in 1981, in a version that eliminated an entire subplot so that the print wouldn’t run past midnight and jack up the theatre’s operating costs.

To make matters more complicated, two different versions of the ‘restored’ Othello have been presented to the public so far, although only the second of these is currently in circulation. The first, worked on in Chicago by a team headed by Michael Dawson and Arnie Saks, premiered at New York’s Lincoln Center late last year; I saw it several weeks afterwards at a private screening in Chicago. Read more

From the November 1, 1992 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last feature (1975) is a shockingly literal and historically questionable transposition of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom to the last days of Italian fascism. Most of the film consists of long shots of torture, though some viewers have been more upset by the bibliography that appears in the credits. Roland Barthes noted that in spite of all its objectionable elements (he pointed out that any film that renders Sade real and fascism unreal is doubly wrong), this film should be defended because it refuses to allow us to redeem ourselves. It’s certainly the film in which Pasolini’s protest against the modern world finds its most extreme and anguished expression. Very hard to take, but in its own way an essential work. In Italian with subtitles. 117 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

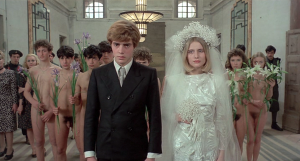

From the Chicago Reader (May 6, 1994). I haven’t reseen The Second Heimat since then, and it would be interesting to discover how it holds up today. — J.R.

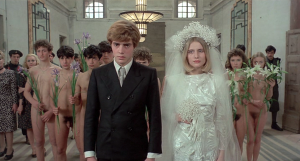

**** THE SECOND HEIMAT

(Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Edgar Reitz

With Henry Arnold, Salome Kammer, Daniel Smith, Noemi Steuer, Armin Fuchs, Martin Maria Blau, Laszlo I. Kish, Frank Roth, Anke Sevenich, Franziska Traub, Michael Schonborn, Hannelore Hoger, Susanne Lothar, Alexander May, and Peter Weiss.

Why is it so hard to be happy? — Clarissa in the seventh episode of The Second Heimat

The 60s and early 70s reveled in long, ambitious works — movies and music alike — epic, multilayered statements that through their unwieldy lengths alone challenged and disrupted the flow of everyday life. In jazz there were Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz and John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, in rock Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, We’re Only in It for the Money, and Tommy, and when rock and movies came together in Woodstock (1970) the running time was three hours — about as long as a marijuana high.

An interesting paradox: to go to a long concert or long movie during that period was to be “somewhere else,” but that didn’t necessarily mean to escape. Read more