From Chicago Reader (August 1, 1998). — J.R.

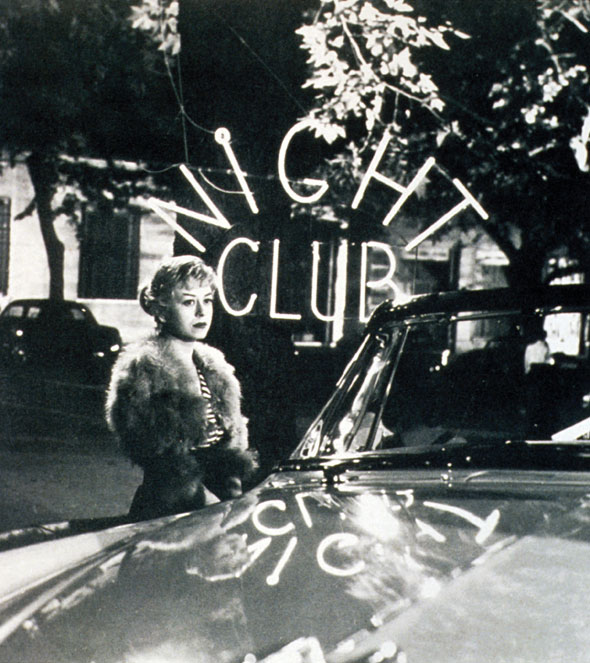

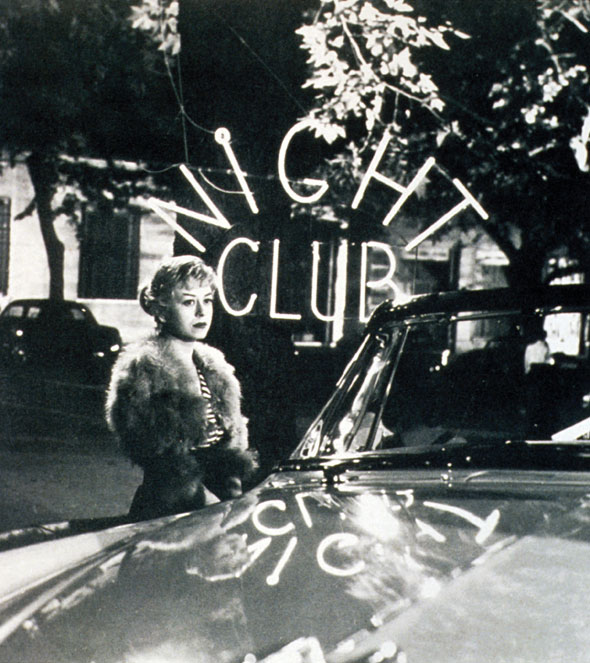

Federico Fellini’s restored 1957 masterpiece, starring his wife, Giulietta Masina. Though the additional scene — an incident involving a man who distributes food and clothing to the homeless — may have little consequence in terms of the overall plot, it changes one’s thematic and spiritual sense of the whole film. The story basically consists of five lengthy episodes in the life and career of a prostitute who repeatedly becomes disillusioned but keeps finding the resources to believe in romantic love just the same. Masina’s exaggerated grimaces and clownlike features, which hark back to the tradition of silent comics, are undoubtedly mannerist, but part of Fellini’s mastery is to make them necessary correlatives to his own vision of innocence. Too melodramatic and fanciful in turn to qualify as neorealism in the usual sense, despite the gritty Roman street slang contributed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, this gains immeasurably, like many other Fellini films, from Nino Rota’s wistful music. In Italian with subtitles. 117 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

East Side Story, a recent documentary about communist musicals, assumes that communist-bloc directors were just itching to make Hollywood extravaganzas and invariably wound up looking strained, square, and ill equipped. But Red Psalm (1971), Miklos Jancso’s dazzling, open-air revolutionary pageant, is a highly sensual communist musical that employs occasional nudity as lyrically as the singing, dancing, and nature; within its own idioms it swings as well as wails. Set near the end of the 19th century, when a group of peasants have demanded basic rights from a landowner and soldiers arrive on horseback, it’s composed of less than 30 shots, each one an intricate choreography of panning camera, landscape, and clustered bodies. Jancso’s awesome fusion of form with content and politics with poetry equals the exciting innovations of the French New Wave in the 60s and early 70s. The music, ranging from revolutionary folk songs to {Charlie Is My Darlin’,} will keep playing in your head for days, and the colors are ravishing. The picture won Jancso a best director prize at Cannes, and it may well be the greatest Hungarian film of the 60s and 70s, summing up an entire strain in his work that lamentably has been forgotten here. Read more