DARKNESS VISIBLE: A MEMOIR OF MADNESS by William Styron (New York: Vintage Books), 1990, 84 pp.

HAVANAS IN CAMELOT: PERSONAL ESSAYS by William Styron (New York: Random House), 2008, 162 pp.

Two late autobiographical books by a writer I’ve always liked —- the first somewhat disappointing, perhaps because I came to it with the wrong expectations, the second a pleasurable surprise.

I guess what I was hoping to encounter in DARKNESS VISIBLE, Styron’s brief and somewhat sketchy account of his own excruciating bouts with depression in the 1980s, was some clarification or extension of what I found so powerful about his treatment of bipolar behavior in SOPHIE’S CHOICE (1979) -– specifically the depiction of Nathan, which seemed to derive from some deep personal understanding of this condition. But Styron points out early on that his own malady was “unipolar,” not the same thing at all. Still, I admire the scrupulous way he avoids leaping to too many conclusions about a condition that he’s still far from fully understanding.

The late essays collected in HAVANAS IN CAMELOT deal with such topics as a few amicable encounters with John F. Kennedy (the title essay), an apparent contraction of syphilis during his youth (as a fledgling Marine at a naval hospital in South Carolina), his friendships with fellow novelists (Truman Capote, James Baldwin, and Terry Southern), some late prostate trouble, and walks with his dog in his early 80s. Read more

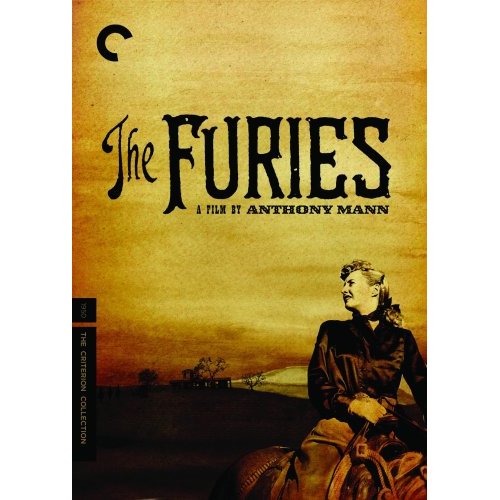

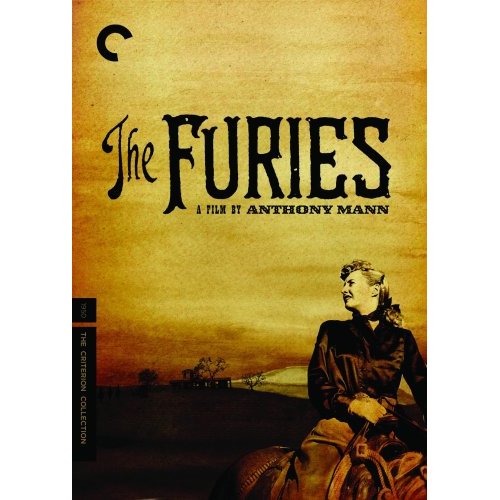

THE FURIES, directed by Anthony Mann (1950, 109 min.), in a Criterion box set.

Last night, I saw this grand, exciting, unruly failure, Mann’s first western, for the first time, thanks to the timely arrival of the DVD from Criterion, handsomely boxed with the Niven Busch novel that Charles Schnee (and Mann, uncredited) adapted it from. I haven’t yet sampled the Jim Kitses commentary, but there’s also an excellent new essay by Robin Wood that’s very attentive to both the strengths and weaknesses of the film, cross-referencing KING LEAR in all the right ways. And on the same disc, a Paul Mayersburg interview with Mann shortly before his death that was recorded for British television–the first I’ve ever seen–as well as a no less revealing interview with Mann’s daughter Nina, which introduces me to certain relevant aspects of Mann’s childhood: specifically, growing up mainly without parents in a Theosophical Institute in San Diego where there was an outdoor amphitheater that produced Greek tragedies, among other things.

My only complaint, really, is that there’s no allusion in the booklet to Arthur Hunnicutt’s uncredited appearance in the film––the same year he appeared as Chloroform Wiggins in Jacques Tourneur’s STARS IN MY CROWN. Read more

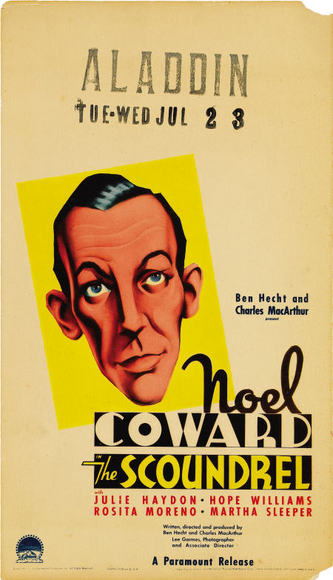

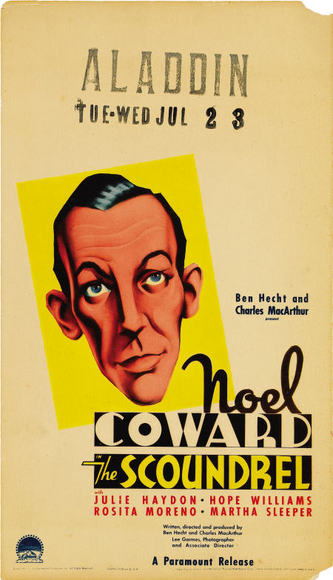

THE SCOUNDREL, written and directed by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, with Noel Coward (1935, 76 min.)

Interesting to discover from Alfred Kazin’s AN AMERICAN PROCESSION -– specifically, from the beginning of his chapter about AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY and THE SOUND AND THE FURY -– that Horace Liveright, the onetime publisher of Dreiser, was “the model for Ben Hecht’s maliciously engaging film THE SCOUNDREL“. Having recently reseen and again hugely enjoyed the second feature codirected as well as cowritten by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, starring Noel Coward in the title role as Anthony Mallare (apparently his first film part, unless one counts his uncredited cameo in Griffith’s 1918 HEARTS OF THE WORLD), I’d been wondering how much of this memorable antihero was attributable to the imaginations of the writer-directors and how much came from life.

Hecht directed or codirected seven features in all, starting with the equally mannerist CRIME WITHOUT PASSION (with its deliriously campy avant-garde prologue) in 1934 and concluding with the rather awful ACTORS AND SIN (codirected by Lee Garmes) in 1952. All of them are difficult to find nowadays, though I’ve managed to track down a few from various Mom and Pop operations on the Internet. Read more