From the Chicago Reader in July 2000. — J.R.

With the possible exceptions of Killer’s Kiss and A Clockwork Orange all of Stanley Kubrick’s features look better now than when they were first released, and Barry Lyndon, which fared poorly at the box office in 1975, remains his most underrated (though Eyes Wide Shut is already running a close second). This personal, idiosyncratic, and melancholy three-hour adaptation of the Thackeray novel may not be an unqualified artistic success, but it’s still a good deal more substantial and provocative than most critics were willing to admit. Exquisitely shot in natural light (or, in night scenes, candlelight) by John Alcott, it makes frequent use of slow backward zooms that distance us, both historically and emotionally, from its rambling picaresque narrative about an 18th-century Irish upstart (Ryan O’Neal). Despite its ponderous pacing and funereal moods, the film is highly accomplished as a piece of storytelling, and it builds to one of the most suspenseful duels ever staged. It also repays close attention as a complex and fascinating historical meditation, as enigmatic in its way as 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Music Box’s weeklong Kubrick retrospective includes a new print of this and several other films, and it offers an excellent opportunity to reevaluate a filmmaker whose work continues to deepen after his death. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 13, 2001). — J.R.

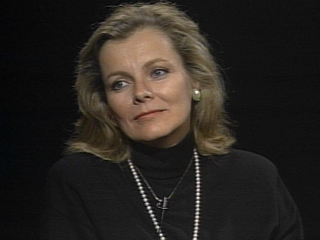

John Cassavetes’s galvanic 1968 drama about one long night in the lives of an estranged well-to-do married couple (John Marley and Lynn Carlin) and their temporary lovers (Gena Rowlands and Seymour Cassel) was the first of his independent features to become a hit, and it’s not hard to see why. It remains one of the only American films to take the middle class seriously, depicting the compulsive, embarrassed laughter of people facing their own sexual longing and some of the emotional devastation brought about by the so-called sexual revolution. (Interestingly, Cassavetes set out to make a trenchant critique of the middle class, but his characteristic empathy for all of his characters makes this a far cry from simple satire.) Shot in 16-millimeter black and white with a good many close-ups, this often takes an unsparing yet compassionate “documentary” look at emotions most movies prefer to gloss over or cover up. Adroitly written and directed, and superbly acted — the leads and Val Avery are all uncommonly good (the astonishing Lynn Carlin was a nonprofessional discovered by Cassavetes, working at the time as Robert Altman’s secretary) — this is one of the most powerful and influential American films of the 60s. Read more

The most gratifying aspect of Peggy Noonan’s eloquent article last Friday in the Wall Street Journal isn’t merely the belated sign that sane and grown-up conservative thought is finally being heard on the subject of the Middle East, in contrast to the obtuse bellicosity and stupid posturing of John McCain and others. Even more, it’s a sign that some Americans are finally beginning to learn something from American mistakes — above all, from the peculiar conviction that American self-aborption is the only thing urgently needed in the world outside the U.S., and that any sign of tact, calm, and/or reticence automatically translates into weakness. (I hasten to add that Noonan’s voice hasn’t been the only sensible one recently coming from the right; I’m emphasizing it only because it seems the loudest and clearest of these voices.)

I would love to see this dawning wisdom take one crucial further step — the recognition that the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 weren’t simply, exclusively, and unproblematically “attacks on America”, whatever that means. They were attacks on people, many of whom weren’t American. Assuming otherwise, as so many chest-beaters did and still do, means playing into the hands of the fanatics who committed these murders and perversely honoring their supposed wisdom and one-dimensional view of the world for the sake of throwing out every other possible reading of what happened. Read more