[2017 Preface: I’m reposting this article less than a month after its last posting on this site because Powerhouse Films in the U.K. has just sent me, at my request, its impressive “Limited Dual Format Edition” of this remarkable movie, and so far, the only complaint I have relevant to its riches is that they didn’t access this 1978 article about it any sooner. If they had, some of the uncertainties and/or wrong guesses made by Glenn Kenny and Nick Pinkerton in their often informative audiocommentary probably wouldn’t be there. For the record then–to cite only a couple of matters not covered in the article below that conflict with their suppositions (apart from the mispronounciation of La Jolla)–in 1953, at age ten, I already knew who Dr. Seuss was because many of his books were already widely available but, even as a devoted radio listener, I didn’t know who Peter Lind Hayes and Mary Healy were.]

The principal source of this article — written for American Film, and published in their October 1978 issue — was a fairly lengthy phone conversation I once had with Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-1991), better known as Dr. Seuss, when I was living in San Diego. Read more

Written for the July-August 2017 Film Comment. This is the unedited version of my review. — J.R.

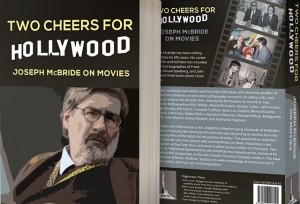

Two Cheers for Hollywood: Joseph McBride on Movies

By Joseph McBride, Hightower Press, $38.50.

Anyone who’s read his astute critical biographies of Capra, Ford, Spielberg, and Welles knows that Joseph McBride is one of our most invaluable film historians. No less ambitious but more personal are his three most recent books, all brought out expertly under his own imprint and available from Amazon: his hefty Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit (2013), his very moving and painfully candid The Broken Places: A Memoir (2015), and now an even heftier volume collecting half a century’s worth of his film journalism and criticism, encompassing 56 separate items and almost 700 large-format pages. It’s the sort of old-fashioned bedside compendium and browser’s paradise that we seldom get nowadays from academic publishers—with a few rare exceptions, such as Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors’ delightful 2009 New Literary History of America (which included one of the better McBride essays reprinted here, “The Screenplay as Genre,” about Citizen Kane). McBride prefaces each piece with a contextualizing introduction, and part of what makes this volume fun is the informal history it offers of McBride’s own taste and career. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 12, 1990). — J.R.

The 26th Chicago International Film Festival includes, at the latest count, 110 features and ten additional programs, spaced out over 15 days in two locations –a somewhat more modest menu than last year’s. Apart from this streamlining, it would be a pleasure to report some major improvements in the overall selection, but I’m afraid wanting isn’t having, and from the looks of things, this year’s lineup is not very inspiring.

About six weeks ago, when the festival issued a list of about 100 “confirmed and invited” films, I was hopeful. Based on what I’d already seen or heard about, the list was, barring some omissions, a fair summary of what was going on in world cinema, which is more than one could say for previous Chicago festival lineups. I pointed this out to a colleague, who replied, “Yeah, but let’s see how many of these actually turn up,” and I’m sorry to say his skepticism was warranted. Gradually, irrevocably, over half of the hottest titles were dropped from the list, including Kira Muratova’s remarkable The Asthenic Syndrome, Jean-Luc Godard’s La nouvelle vague, Nanni Moretti’s Palombella Rosa, Pavel Lounguine’s Taxi Blues, Charles Burnett’s soon-to-open To Sleep With Anger, Aki Kaurismaki’s The Match Factory Girl, Bertrand Tavernier’s Daddy Nostalgy, Otar Iosseliani’s Et la lumiere fut, and Patrice Leconte’s The Hairdresser’s Husband. Read more