From Sight and Sound (October 1992). –- J.R.

Most of the American press has been all too happy to declare the new version of Orson Welles’ Othello as “expertly restored”, as Vincent Canby put it in the New York Times. But restored from what and to what? Even rudimentary information about the film’s original form is not easy to come by in the U.S., where 0thello brought in only $40,000 on its belated first release in 1955 and has been screened only sporadically since. Mutatis mutandis, the acclaim that has greeted the restoration recalls the unqualified press endorsements of Francis Coppola’s presentation of Abel Gance’s ‘complete’ Napoléon at Radio City Music Hall in 1981, in a version that eliminated an entire subplot so that the print wouldn’t run past midnight and jack up the theatre’s operating costs.

To make matters more complicated, two different versions of the ‘restored’ Othello have been presented to the public so far, although only the second of these is currently in circulation. The first, worked on in Chicago by a team headed by Michael Dawson and Arnie Saks, premiered at New York’s Lincoln Center late last year; I saw it several weeks afterwards at a private screening in Chicago. Read more

From the November 1, 1992 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

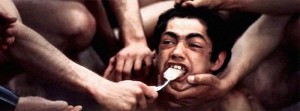

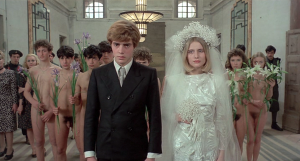

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last feature (1975) is a shockingly literal and historically questionable transposition of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom to the last days of Italian fascism. Most of the film consists of long shots of torture, though some viewers have been more upset by the bibliography that appears in the credits. Roland Barthes noted that in spite of all its objectionable elements (he pointed out that any film that renders Sade real and fascism unreal is doubly wrong), this film should be defended because it refuses to allow us to redeem ourselves. It’s certainly the film in which Pasolini’s protest against the modern world finds its most extreme and anguished expression. Very hard to take, but in its own way an essential work. In Italian with subtitles. 117 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 6, 1994). I haven’t reseen The Second Heimat since then, and it would be interesting to discover how it holds up today. — J.R.

**** THE SECOND HEIMAT

(Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Edgar Reitz

With Henry Arnold, Salome Kammer, Daniel Smith, Noemi Steuer, Armin Fuchs, Martin Maria Blau, Laszlo I. Kish, Frank Roth, Anke Sevenich, Franziska Traub, Michael Schonborn, Hannelore Hoger, Susanne Lothar, Alexander May, and Peter Weiss.

Why is it so hard to be happy? — Clarissa in the seventh episode of The Second Heimat

The 60s and early 70s reveled in long, ambitious works — movies and music alike — epic, multilayered statements that through their unwieldy lengths alone challenged and disrupted the flow of everyday life. In jazz there were Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz and John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, in rock Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, We’re Only in It for the Money, and Tommy, and when rock and movies came together in Woodstock (1970) the running time was three hours — about as long as a marijuana high.

An interesting paradox: to go to a long concert or long movie during that period was to be “somewhere else,” but that didn’t necessarily mean to escape. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 22, 1991). — J.R.

GUILTY BY SUSPICION

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Irwin Winkler

With Robert De Niro, Annette Bening, George Wendt, Patricia Wettig, Sam Wanamaker, Barry Primus, Gailard Sartain, Chris Cooper, Ben Piazza, and Martin Scorsese.

There are plenty of bones one can pick with Guilty by Suspicion, the first Hollywood feature devoted in its entirety to the film-industry blacklist (The Front dealt with TV). Of course there are plenty of bones one can pick with just about any movie, if one is so inclined. But critics, at least, seem more inclined to be so inclined with movies that deal with political subjects. This is not to say that most critics reprove such movies on political grounds; on the contrary, they usually harp on other aspects. But one still winds up feeling that it’s frequently the politics that gets their hackles up.

Having seen this movie more than a week later than most of my colleagues, due to some interesting circumstances that I’ll discuss later, I’ve had ample opportunity to read and (more often) hear some of their carping, most of it hyperbolic invective about the acting and directing. Some of them have expressed so much antipathy for the picture that I went to the first screening at Webster Place last weekend expecting the worst. Read more

From the August 17, 2001 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Apocalypse Now Redux

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Written by John Milius and Coppola

With Martin Sheen, Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms, Laurence Fishburne, Dennis Hopper, G.D. Spradlin, Harrison Ford, Colleen Camp, Cynthia Wood, Christian Marquand, and Aurore Clement.

It’s hard to think of many movies where the great, the not so great, and the simply awful coexist quite as brazenly as they do in Apocalypse Now. This was true in 1979, when the movie clocked in at 150 minutes, and it’s true 22 years later, when the new version, Apocalypse Now Redux, runs a third longer.

If anything, the longer version — not so much a rethinking of the material as an expansion, with a minimum of reshuffling, by the adept Walter Murch, who also worked on the original — is better and worse, emphasizing both the ambitious scope and the fatal flaws of Francis Ford Coppola’s achievement. Among the more substantial additions are a ghostly sequence set on a French plantation (featuring Aurore Clement and the late Christian Marquand) that tries, with mixed results, to poeticize the futility of outsiders, French or American, getting involved in the Vietnam war and a silly and rather inconclusive sequence involving a couple of Playboy Playmates (Cynthia Wood and Colleen Camp) that adds nothing. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 15, 1991). — J.R.

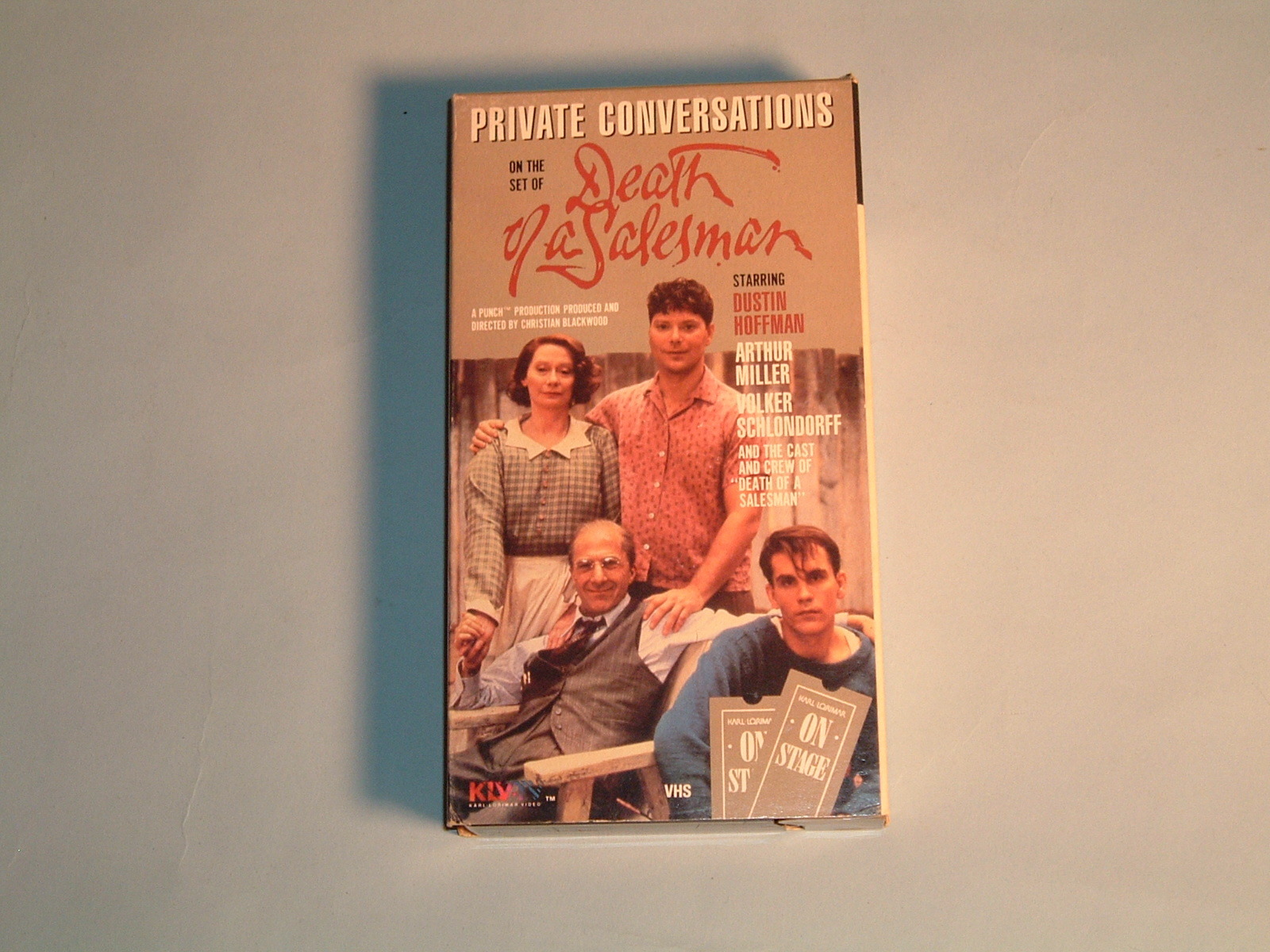

PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS: ON THE SET OF DEATH OF A SALESMAN

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Christian Blackwood.

I’ve never seen Volker Schlondorff’s 150-minute made-for-TV film of Death of a Salesman (1985), which Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies awards high marks: “Stunning though stylistic remounting of [Dustin] Hoffman’s Broadway revival of the classic Arthur Miller play with most of the cast from that 1984 production. A landmark of its type. Executive-produced by Hoffman and Miller. Hoffman and [John] Malkovich both won acting Emmys. Above average.” But a friend who has seen it, and who loves the play, tells me that she disliked the film: all the actors seemed to be off on their own tangents, she said, and there was little interplay between them.

Whether the Schlondorff film is good or bad, Private Conversations: On the Set of Death of a Salesman, the 82-minute documentary that Christian Blackwood made about the making of it, is endlessly fascinating, for reasons largely irrelevant to the worth of the Miller play or this particular production of it. Part of the open-endedness of Blackwood’s film comes from the fact that if Schlondorff’s film works the reasons are here, and if it doesn’t work the reasons are here — perhaps in the same circumstances. Read more

This appeared in the August 26, 1994 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

*** DIVERTIMENTO

(A must-see)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Pascal Bonitzer, Christine Laurent, and Rivette

With Michel Piccoli, Jane Birkin, Emmanuelle Béart, David Bursztein, Gilles Arbona, Marianne Denicourt, and the hand of Bernard Dufour.

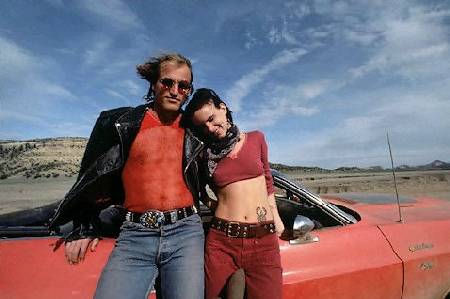

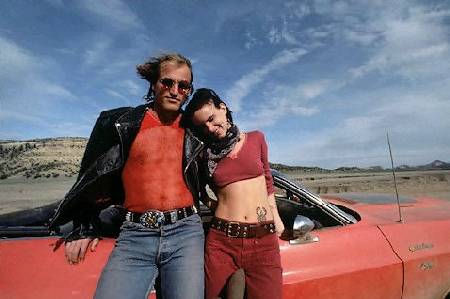

NATURAL BORN KILLERS

(No stars–Worthless)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by David Veloz, Richard Rutowski, Stone, and Quentin Tarantino

With Woody Harrelson, Juliette Lewis, Robert Downey Jr., Tommy Lee Jones, Tom Sizemore, Rodney Dangerfield, Edie McClurg, Sean Stone, and Russell Means.

One of the more deceitful explanations for the compulsive repetition that informs most contemporary movies is that Hollywood is simply giving the public what they want. The idea that they even know what they want is pretty dubious to begin with — especially if one factors out all the publicity and hype that supposedly speaks for them. And the argument that moviemakers have any better sense of what the public wants is usually self-serving propaganda.

A more likely explanation for all the recycling is that it serves business interests — and contrary to what you read in Variety and Premiere, that is not necessarily the same thing as serving the public. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1991). — J.R.

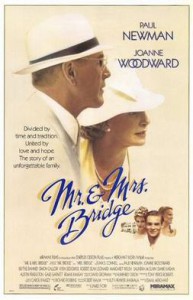

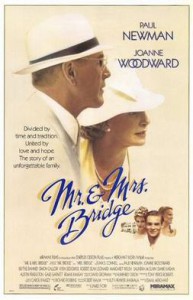

I’m not much of a James Ivory fan, but this 1990 adaptation of Evan S. Connell’s novels Mrs. Bridge (1959) and Mr. Bridge (1969) deserves to be seen and cherished for at least a couple of reasons: first for Joanne Woodward’s exquisitely multilayered and nuanced performance as India Bridge, a frustrated, well-to-do WASP Kansas City housewife and mother during the 30s and 40s; and second for screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s retention of much of the episodic, short-chapter form of the books. It’s true that she and Ivory have toned down many of the darker aspects, but as critic Georgia Brown has suggested, Woodward’s humanization of her character actually improves on the original. Connell’s imagination and compassion regarding this character have their limits, and Woodward triumphantly exceeds them. There are other fine performances as well from Paul Newman (as uptight Mr. Bridge), Blythe Danner (as India’s troubled best friend), Simon Callow, and Austin Pendleton. If the Bridges’ three children are realized less acutely than their parents, the period portraiture nonetheless shows a great deal of taste and intelligence. With Kyra Sedgwick and Robert Sean Leonard. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1991). — J.R.

An engaging, exciting noir thriller (1952) set almost entirely on a train going from Chicago to Los Angeles, with a gruff cop (Charles McGraw) guarding a saucy prosecution witness (the underrated Marie Windsor). Richard Fleischer directed this nearly perfect B picture with no fuss and lots of grit and polish from a script by Earl Fenton; the capable cinematography belongs to George E. Diskant. 70 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

For the Chicago Reader (August 23, 1991). Fortunately, I’ve been to Austin quite a few times since I wrote this review. — J.R.

Richard Linklater’s delightfully different and immensely enjoyable first feature takes us on a 24-hour tour of the flaky dropout culture of Austin, Texas; it doesn’t have a continuous plot, but it’s brimming with weird characters and wonderful talk (all of it scripted by Linklater, though it often seems improvised). The structure of dovetailing dialogues calls to mind an extremely laid-back variation on The Phantom of Liberty or Playtime. “Every thought you have fractions off and becomes its own reality,” remarks Linklater himself to a poker faced cabdriver in the first (and in some ways funniest) scene, and the remainder of the movie amply illustrates this notion with its diverse paranoid conspiracy and assassination theorists, serial-killer buffs, musicians, cultists, college students, pontificators, petty criminals, street people, and layabouts (around 90 in all). Even if the movie goes nowhere in terms of narrative and winds up with a somewhat arch conclusion, the highly evocative scenes give an often hilarious sense of the surviving dregs of 60s culture and a superbly localized sense of community. I’ve never been to Austin, but this movie certainly makes me want to pay a visit (1990). Read more

From the February 22, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Try to imagine Siskel and Ebert not as Chicago film critics but as a heterosexual couple in Baltimore, both of them general interest reporters whose combative instincts and political and temperamental differences become the focus of a TV show, and you more or less have the premise of this romantic comedy. Kevin Bacon and Elizabeth Perkins play the leads, and a real-life couple (Ken Kwapis and Marisa Silver) direct the separate versions of their story (both scripted by Brian Hohlfeld). The attempt to tell the same story twice from separate viewpoints a la Rashomon or Les Girls doesn’t always yield as much ambiguity or complexity as one might wish. But on the whole, this is an honorable attempt to revive the feeling and ambience of a Hoilywood comedy of the 50s, complete with sumptuous romantic music (score by Miles Goodman), ‘Scope framing, and a magical last-minute resolution, and, as such, it’s pretty pleasurable to watch. With Sharon Stone. (Esquire, Norridge, Old Orchard, Webster Place, Ford City, Lincoln Village)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1996). — J.R.

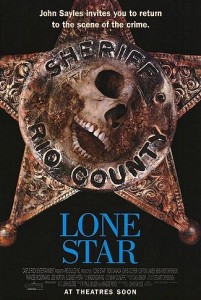

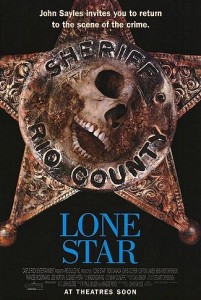

A well-constructed but rather unthrilling mystery thriller (1996) by John Sayles, filmed on location in a Texas border town, with a likable lead performance by Chris Cooper as a laid-back sheriff. The plot is intricate and ambitious, with nine other major characters (played by Elizabeth Peña, Kris Kristofferson, Miriam Colon, Frances McDormand, Joe Morton, Matthew McConaughey, Ron Canada, Eddie Robinson, and Clifton James), various flashbacks, and an exploration of history, corruption, racial persecution, and multiculturalism. The whole thing’s so worthy that I wish I liked it more. It makes time pass agreeably, but Square John still seems about as innocent of fresh ideas (aesthetically and otherwise) as most of his characters, and for this kind of leftist multiplot I found his City of Hope (1991) more engaging. Anecdotal aside: all the black extras in this movie had to be bused in for the filming. 134 min.

Read more

Read more

From the December 6, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

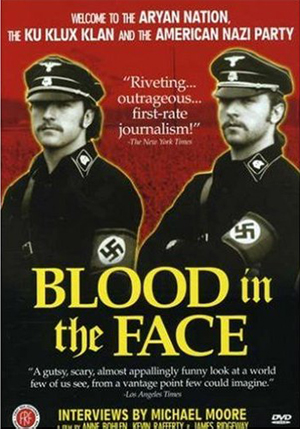

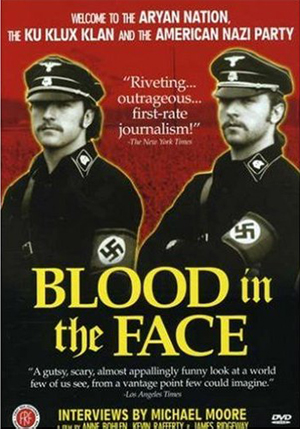

BLOOD IN THE FACE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Anne Bohlen, Kevin Rafferty, and James Ridgeway

If memory serves, it was around my junior year in college, during the mid-60s, when a conservative classmate took my brother and me to a John Birch Society meeting in Hyde Park, New York, held inside a trailer in a trailer camp. The friend advised us to conceal our identities as liberal Jews (he was half Jewish himself) and try to blend in with the surroundings, which we did.

It was a sparsely attended meeting. Before that we made small talk with the handful of other people present — including the couple who owned the trailer and a young man who identified himself as the son of communists and who cheerfully explained that the society had deliberately adopted the structure of the Communist Party, complete with cell meetings like this one and vows of secrecy. He and everyone else in the room seemed friendly, normal everyday folks, until the film projector blew a fuse just as they began to screen a movie.

Then the paranoid speculations began: they made extensive flashlight searches of the yard around the trailer, looking for spies and saboteurs. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Winter 1990/91). -– J.R.

It’s no secret that serious film criticism in print has become an increasingly scarce commodity, while ‘entertainment news’, bite-size reviewing and other forms of promotion in the media have been steadily expanding. (I’m not including academic film criticism, a burgeoning if relatively sealed-off field which has developed a rhetoric and tradition of its own-the principal focus of David Bordwell’s fascinating recent book, Making Meaning) But the existence of serious film commentary on film, while seldom discussed as an autonomous entity, has been steadily growing, and in some cases supplanting the sort of work which used to appear only in print.

I am not thinking of the countless talking-head ‘documentaries’ about current features — actually extended promos financed by the studios or production companies — which include even such a relatively distinguished example as Chris Marker’s AK (1985), about the making of Kurosawa’s Ran. The problem with these efforts is that they further blur the distinction between advertising and criticism, and thus make it even harder for ordinary viewers to determine whether they are being informed about something or simply being sold a bill of goods. What I have in mind are films about films and film-makers which seriously analyse or document their subjects. Read more

This appeared in the Chicago Reader (September 16, 1994). — J.R.

**** THE BLUE KITE

(Masterpiece)

Directed by Tian Zhuangzhuang

Written by Xiao Mao

With Zhang Wenyao, Chen Xiaoman, Lu Liping, Pu Quanxin, Li Xuejian, Guo Baochang, Zhong Ping, and Chu Quanzhong.

Covering 15 years of modern Chinese history, from 1953 to 1968, The Blue Kite is powerful less for what it says about continuity in history than for what it implies about history disrupting people’s lives. The two things that matter most to Tietou, the fictional hero, apart from his mother, are the courtyard just off the Dry Well Lane apartment where his parents move in the opening scene and the title toy — actually a series of toys — he’s given to play with by his father. Each blue kite we see over the course of the film winds up getting stuck in one of the courtyard’s trees and needs to be replaced; more or less the same thing happens with the Tietou’s father (eventually supplanted by two stepfathers) and Tietou’s sense of home, not to mention his sense of identity. All that he retains, and only after a struggle, is a certain sense of morality bequeathed by his mother and a certain sense of place bequeathed by the courtyard. Read more