From the Chicago Reader (March 9, 2007). — J.R.

BAMAKO ****

DIRECTED AND WRITTEN BY ABDERRAHMANE SISSAKO | WITH AISSA MAIGA, TIECOURA TRAORE, HELENE DIARRA, ROLAND RAPPAPORT, AMINATA DRAMANE TRAORE, DANNY GLOVER, AND ELIA SULEIMAN

Before the main title of Abderrahmane Sissako’s startling new feature appears, an elderly farmer arrives at a hearing that’s being held in a shared backyard in a poor section of Bamako, the capital of Mali. He’s there to testify, but when he steps up to the microphone he’s told politely to remove his hat and wait his turn.

What’s on trial in this backyard court is globalization, particularly the high-interest loans of such organizations as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and the pressure they put on governments to cut costs by privatizing or ending social services and firing workers. Unlike the seemingly random everyday details that surround the mock trial — small talk, the performances of a pop singer in a club, the illness of the singer’s daughter, a wedding, clothes being dyed or hung out to dry — this public reckoning is obviously staged. A year before he began filming, Sissako hired the judge, prosecutors, and defense attorneys, real lawyers who wrote their own dialogue, mainly in French (we’re often reminded that Mali is a former colony of France). Read more

From the April 6, 2007 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

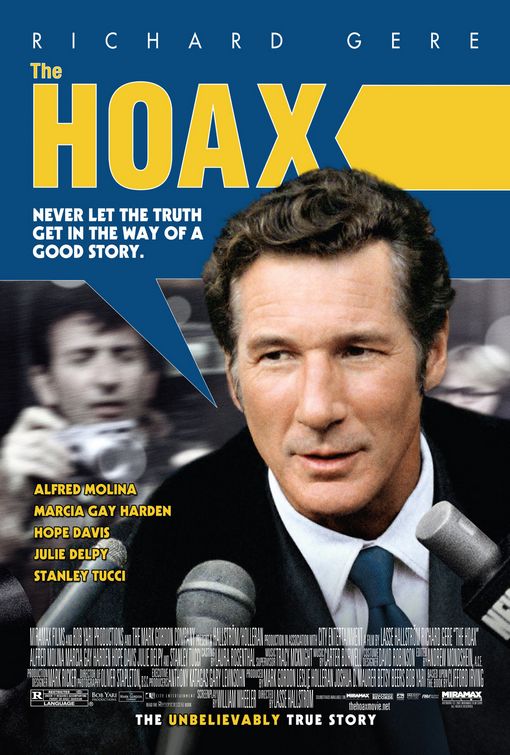

THE HOAX * DIRECTED BY LASSE HALLSTROM

WRITTEN BY WILLIAM WHEELER, FROM A BOOK BY CLIFFORD IRVING WITH RICHARD GERE, ALFRED MOLINA, HOPE DAVIS, MARCIA GAY HARDEN, STANLEY TUCCI, AND JULIE DELPY

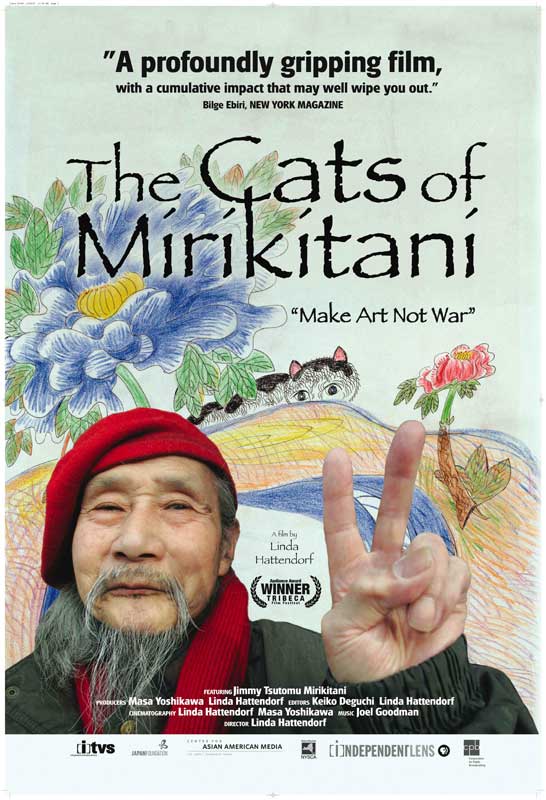

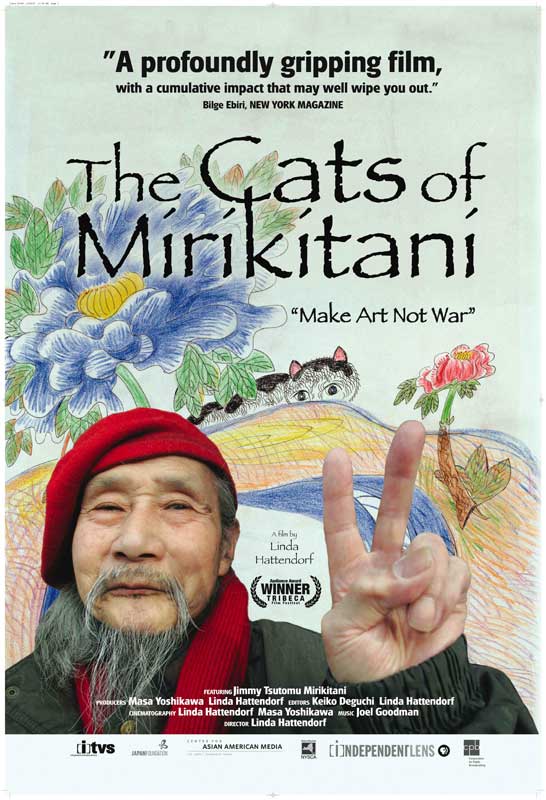

THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI*** DIRECTED BY LINDA HATTENDORF

There are ways both official and unofficial to describe “the movies.” There’s the new releases the industry decides to push in the malls, and then there’s everything else, which we’re obliged to root out for ourselves. A schoolteacher I know in the wilds of Argentina selects and projects DVDs on a regular basis, and some of the stuff he shows — old experimental shorts, recent features by Abbas Kiarostami, Alexander Sokurov, and Gus Van Sant — is pretty specialized. But he must know his audience at least as well as any studio, because his screenings draw about 800 people a week.

I’d like to think that kind of niche viewing is the wave of the future, something that will put a lot of mall fare to shame. And applying this notion to a couple of features opening this week, I’d like to think that a quietly precious piece of artfully arranged storytelling like The Cats of Mirikitani and a brassy piece of bluster like The Hoax represent respectively the future and present of movies. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 31, 2007). — J.R.

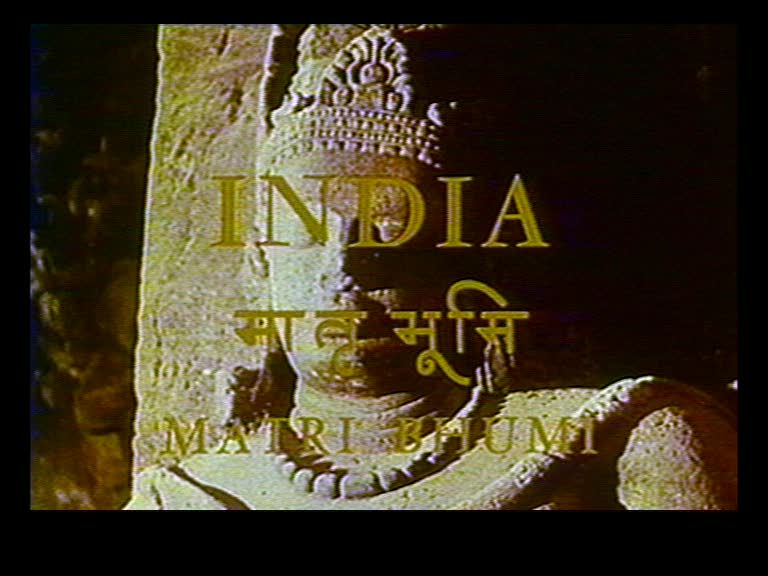

INDIA MATRI BHUMI ****

DIRECTED BY ROBERTO ROSSELLINI

WRITTEN BY ROSSELLINI, SONALI SENROY DAS GUPTA, FEREYDOUN HOVEYDA, AND JEAN L’HOTE

WITH A NONPROFESSIONAL, UNCREDITED CAST

From the beginning film has owed part of its fascination to its ambiguous marriage of documentary and fiction. Just after the war Roberto Rossellini came to prominence as a filmmaker through combinations of this kind. His best-known early works, Open City (1945) and Paisan (1946), are associated with the style popularly known as Italian neorealism, but through the 50s Rossellini experimented with increasingly adventurous mixes of reality and invention, culminating in 1959 with India Matri Bhumi, whose title means “India, Mother Earth.” It’s a sublime symbiosis of fable and nonfiction that poetically inter-relates humans and animals, city and village, society and nature.

At war’s end Rossellini was primarily concerned with the human devastation in Italy and Germany. But once he began working with Ingrid Bergman, with whom he was living after their affair busted up both their marriages, domestic issues started coming to the fore, particularly in such features as Europa 51, Voyage to Italy, and Fear. The Bergman films flopped both critically and commercially, though for the young critics of Cahiers du Cinema they were models of personal independent filmmaking that would help spark the French New Wave. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 29, 2007). — J.R.

In this propagandistic but well-paced cold-war adventure (1954), a mercenary submarine captain (Richard Widmark) helps foil a Red Chinese plot to drop an atomic bomb on Korea from a U.S. plane. Fox hired director Samuel Fuller to shoot this in a few days, partly to prove that CinemaScope could work in tight spaces and on a limited budget, and he did a pretty good job with it. He even got to rewrite the script, defiantly giving Widmark a variant of the salty, unpatriotic line that J. Edgar Hoover had already tried and failed to get Fuller to delete from Pickup on South Street: “Are you waving the flag at me?” With Cameron Mitchell, David Wayne, Fuller regular Gene Evans, and Bella Darvi, the mistress of studio chief Darryl Zanuck. 103 min. (JR)

Read more

Last night, the final session of “Cinema of Tomorrow,” a symposium held over the last three days at the Mar del Plata International Film Festival, was my own, derived from an article that just appeared in the Spring issue of Film Quarterly: “Film Writing on the Web: Some Personal Reflections.” But as I interjected at one point, a more accurate title might have been, “Film Writing in English on the Web.”

The symposium was effectively organized by my friend Quintin (see photo, second from left) so that the six presentations over three days had a logical flow and development: two rather pessimistic analyses of the way film festivals operate, including Mar del Plata, by Peter van Bueren from Amsterdam and Mark Peranson from Vancouver (whose papers I briefly summarized in former posts); two looks at contemporary trends in films by Emmanuel Burdeau from Paris (who emphasized themes of globalization in films by Abbas Kiarostami, Hou Hsiao-hsien, and Jia Zhangke, among others) and Cristina Nord from Berlin (who offered fascinating comparisons between new Argentinean cinema and new German cinema, both strengthened as well as hampered by the task of coping with a dark political past); and on the final day, two rather optimistic analyses of contemporary cinephilia by Alvaro Arroba from Madrid and myself.

Read more

I miss the relative funkiness of Raul Ruiz’s low-budget films, but this internationally produced feature (2006) is probably the best of his more opulent work since Time Regained (1999). A series of speculative riffs on the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, it stars John Malkovich in the title role. Unfortunately the Film Center has been able to book only the producer’s cut of the film, which is half an hour shorter than the version shown in France but feels half an hour longer. It’s been cut as if it were a biopic and sometimes registers as a failed one. But it’s still an eyeful. 97 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 26, 2007). — J.R.

David Lynch’s first digital video is his best and most experimental feature since Eraserhead (1978). Shot piecemeal over at least a year and without a script, this 179-minute meditation builds on Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001) as a sinister and critical portrait of Hollywood. But it resists any narrative paraphrase, with several overlapping premises rather than a single consecutive plot. Laura Dern plays an actress who’s been cast in a new feature, as well as a battered housewife and a hooker; there are also Polish characters and a sitcom with giant rabbits in human clothes. The visual qualities include impressionistic soft-focus colors, expressionistic lighting, and disquietingly huge close-ups. With Justin Theroux, Jeremy Irons, Karolina Gruszka, Harry Dean Stanton, and Grace Zabriskie. In English and subtitled Polish. R. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This essay, reprinted in my 2010 book Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, appeared in French translation in Le Mythe du Director’s cut (Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2008), a collection coedited by Michel Marie and François Thomas and adapted from a lecture I gave at a conference about “directors’ cuts” that was held at the Toulouse Cinémathèque in early 2007. I should add that this was written prior to the release of Blade Runner: The Final Cut, which I subsequently reviewed in the November 1, 2007 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Perhaps the biggest source of confusion regarding the term “director’s cut” is the fact that it can serve both as a legal concept and as an advertising slogan, and both as an aesthetic theory and as an actual aesthetic praxis. In some instances, it can serve all of these functions, but I would argue that most of these instances occur in France —-the only country, to my knowledge, where the legal concept is backed up by an actual law pertaining to les droits d’auteur. And even here, I’ve been told that this law is not always and invariably a guarantee of artistic freedom. A few years ago, while he was working on Le temps retrouvé, Raúl Ruiz told me in effect that in some cases it could function as a law that took on the characteristics of a deceitful advertising slogan—-which is to say, that it doesn’t always function as an enforceable law, especially when larger sums of money are involved and various kinds of coercion are available to producers who want to impose their will on certain creative decisions made by filmmakers. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 22, 2007). — J.R.

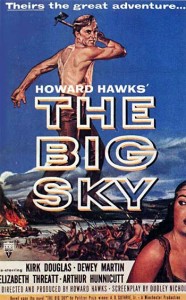

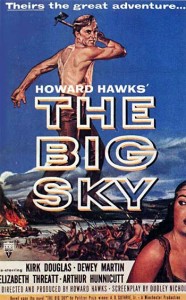

Though this sublime 1952 black-and-white masterpiece by Howard Hawks is usually accorded a low place in the Hawks canon, it’s a particular favorite of mine — mysterious, beautiful, and even utopian in some of its sexual and cultural aspects. Adapted (apparently rather loosely) by Dudley Nichols from part of A.B. Guthrie’s novel, this adventure stars Kirk Douglas and Dewey Martin as Kentucky drifters who join an epic trek up the Missouri River, along with the latter’s uncle (Arthur Hunnicutt), an Indian princess (Elizabeth Threatt), and a good many Frenchmen. The poetic feeling for the wilderness is matched by the camaraderie, yet there’s also a tragic undertone to this odyssey that seems quintessentially Hawksian — a sense of a small human oasis in the center of a vast metaphysical void. 140 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

The final intertitle of Nina Davenport’s 2007 documentary — “I had hoped for a happy ending . . . now I’m just looking for an exit strategy” — aptly suggests the parallel between the endless string of misjudgments that created the so-called Iraqi war and the ones that created this film about it. Spotting on MTV a 25-year-old Iraqi film student, Muthana Mohmed, whose school in Baghdad had been leveled by American bombs, Hollywood actor Liv Schreiber got the lousy idea of hiring him as a gofer on his lousy first feature as a director, Everything Is Illuminated, which was shot in Prague. Assigned to film Mohmed’s experiences, Davenport (who also had a crew filming his friends and family back home) soon found herself stuck with someone she didn’t like whose need to live his own life was incompatible with hers to finish her film. Nobody comes off well in this tragicomedy, about mutual exploitation by people who don’t know what they’re doing. But the eventual rude awakenings, among them Davenport’s, are thoughtful and enlightening — well worth the wait. 95 min. (JR) Read more

Inspired by Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, this beautiful documentary by John Gianvito (The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein) documents not only graves and memorials across the U.S. for people (both famous and unknown) who died in political struggles, but also the surrounding landscapes that nestle and sometimes hide these largely unremarked sites. The casual way Gianvito introduces us to these settings via sound and image, the varying cinematic means employed (including stretches of animation), and the powerful maximal effects he achieves from his supposedly minimalist agenda are all essential facets of the film’s haunting poetry. This was named best experimental film of 2007 by the National Society of Film Critics, but it also displays a strong passion for history–including film history, from Griffith, Stroheim, and Dovzhenko to Straub-Huillet. 58 min. a Gene Siskel Film Center. —Jonathan Rosenbaum Read more

Two hypnotic and haunting 2007 features by Spanish experimental filmmaker Jose Luis Guerin, about the same romantic obsession. (The reference points are W.G. Sebald’s novel Vertigo and Alfred Hitchcock’s film of the same title.) The silent Some Photos in the City of Sylvia (65 min.) uses black-and-white stills with English intertitles to recount an unseen artist’s return to Strasbourg to search for a young woman he met briefly 22 years earlier while making a Goethe-related literary pilgrimage. The far more elliptical In the City of Sylvia (84 min.) tells the same story with color, carefully articulated sound, and minimal, subtitled French dialogue; in this film the artist returns only six years after his pilgrimage. Both works are mysterious, beautiful, and primal. It’s a pity the first, an intimate study and scenario for the second, is being shown after only one screening of its more languid successor. (JR)

Read more

Now that it’s winter, it shouldn’t be surprising that a large part of the American populace seems locked into some sort of hibernation mode–a state of mind that suggests that virtually all of the country’s problems can be blamed on George W. Bush and virtually none of them can be blamed on the people who voted for George W. Bush. But a more immediate problem is one that involves adjusting to the fact that the very long and recently concluded presidential campaign is no longer in operation. Milk addresses a mindset I would associate with campaign agitprop mode, a mindset that forsakes nuanced and complex analysis for the sake of immediate uplift; The Order of Myths addresses us in a more analytical mode. Of course, given the outlawing of same-sex marriage in California in the last election, an election-mode form of agitprop may be more functional at the moment, at least where homophobia is concerned, but this doesn’t necessarily entail more thoughtful filmmaking.

As nearly as I can remember, Mobile is the only city in Alabama of any significant size that I never visited during the first 16 years of my life, when I was growing up in that state—nor have I ever made it to Mobile since. Read more

Ahmad Jamal Complete Live at the Spotlite Club 1958 (2-CD set, Gambit Records 69265).

You may have to be an Ahmad Jamal completist like myself to take notice of this 2007 expanded edition, which adds three 1958 Chicago studio cuts, totaling about eight minutes, to the 25 live ones that have already been available. The latter tracks appeared on two well-known Jamal LPs, Ahmad Jamal and the two-disc Portfolio of Ahmad Jamal, both recorded in September 1958 at Washington, D.C.’s Spotline Club in September 5 and 6, 1958.

If memory serves, the first of these was the first Jamal record I ever bought, when I was 15 or 16, and it’s never gone stale for me —- despite the scorn heaped on Jamal by sophisticated jazz critics such as Martin Williams in Downbeat. There’s always been a curious split between the Jamal idolatry of Miles Davis –- who joined forces with Gil Evans on their first joint album to virtually steal (rather than simply play homage to) two tracks from Jamal’s 1955 Chamber Music of the New Jazz, “New Rumba” and “I Don’t Wanna Be Kissed,” and based his Quintet’s arrangement of “All of You” in ‘Round Midnight on Jamal’s on the same LP —- and the disdain of most jazz critics, who seemed to regard Jamal’s popularity with seething resentment, much as they resented Dave Brubeck during the same period. Read more

Last month, roughly thirty-five years after its publication, the small, Denver-based publisher Arden Press finally declared my book Film: The Front Line 1983 out of print, with 192 copies remaining in stock. A commissioned work designed to launch an annual series surveying independent and experimental filmmaking, it yielded only one other volume after my own, David Ehrenstein’s equally useful Film: The Front Line 1984— which, like my book, can still be readily found at bargain prices at Amazon and elsewhere.

I have somewhat mixed feelings about some of the disgruntled patches of score-settling and related polemics in my book, although there are other patches that I still like. A few chapters have already been posted on this site, and I expect that others will follow.

To the best of my recollection, I found copies of this book on the shelves of only two bookstores: the long-gone Coliseum Books (1974-2007) just below Columbus Circle in New York, the same year (1983) it was published, and the first bookstore I ever walked into, quite at random, in Melbourne–still recovering from jetlag, and not quite believing my eyes–on the first of my three visits to Australia, in 1996. I’m sorry that I no longer remember the name of that store, because it certainly made my day. Read more