From the Chicago Reader (October 23, 1992). — J.R.

Apart from his final feature, Salo, this is probably Pier Paolo Pasolini’s most controversial film, and to my mind one of his very best, though it has the sort of audacity and extremeness that sends some American audiences into gales of derisive, self-protective laughter. The title is Italian for “theorem,” in this case a mythological figure: an attractive young man (Terence Stamp) who visits the home of a Milanese industrialist and proceeds to seduce every member of the household — father (Massimo Girotti), mother (Silvana Mangano), daughter (Anne Wiazemsky), son (Andés José Cruz Soublette), and maid (Laura Betti). Then he leaves, and everyone in the household undergoes cataclysmic changes. Pasolini wrote a parallel novel of the same title, part of it in verse, while making this film; neither work is, strictly speaking, an adaptation of the other, but a recasting of the same elements, and the stark poetry of both is like a triple-distilled version of Pasolini’s view of the world–a view in which Marxism, Christianity, and homosexuality are forced into mutual and scandalous confrontations. Like Pasolini at his best, this is an “impossible” work: tragic, lyrical, outrageous, indigestible, deeply felt, and wholly sincere (1968). Read more

According to Wikipedia, this English-America MGM release about an American teenager (Elizabeth Taylor at 17 playing someone a year older) falling in love with and marrying a 40ish British officer (Robert Taylor) whom she belatedly discovers is a Communist spy — effectively directed by Victor Saville, and recently shown on TCM — lost the studio over $800,000, but it doesn’t say or suggest why. I would guess that this was because, intentionally or not, the film manages to persuade us to identify with the tormented middle-aged spy more than with the tormented patriotic heroine. This isn’t a matter of ideology but a function of how the story gets told. The screenplay by Sally Benson (whose stories provided the basis for MGM’s Meet Me in St. Louis) focuses more on the inner conflicts and secret meetings of the spy than those of the callow girl that he falls for and marries, and the fact that the movie literally ends with her agreeing to lie to everyone about her husband’s suicide to support her own country makes his own deceits seem less reprehensible. It’s a funny paradox that a rabid right-winger like Robert Taylor should make us care so much for a Communist spy, but he does. Read more

From the August 28, 1992 Chicago Reader; reprinted in my collection Placing Movies. — J.R.

THE PANAMA DECEPTION

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Barbara Trent

Written by David Kasper

Narrated by Elizabeth Montgomery.

DEEP COVER

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Bill Duke

Written by Henry Bean and Michael Tolkin

With Larry Fishburne, Jeff Goldblum, Victoria Dillard, Charles Martin Smith, Sydney Lassick, Clarence Williams III, Gregory Sierra, and Roger Guenveur Smith.

I wonder how many people under 35 know that one of the most frequent taunts hurled at President Lyndon Baines Johnson during antiwar demonstrations at the height of the Vietnam war was, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” Johnson did considerably more than any other U.S. president of this century to turn the civil rights movement into law — even going so far as to appropriate the movement’s theme song, “We Shall Overcome,” for a speech to Congress. But because of his behavior regarding nonwhites overseas, especially in Southeast Asia, a considerable part of the youth of the late 60s regarded him as a mass murderer, and told him so on every possible occasion. It seems plausible that Johnson’s decision not to seek reelection in 1968, announced only four days before Martin Luther King was assassinated, had more than a little to do with the repeated sting of that relentless chant. Read more

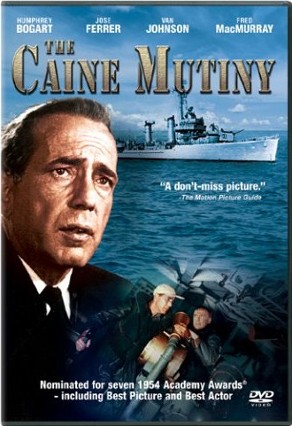

In “Being Orson Welles,” Melena Ryzik’s January 15 interview with Christian McKay in “The Carpetbaggers” (“The Awards Season Blog at the New York Times”), she has McKay say the following: “I love the fact that he was as labyrinthine as one of his greatest creations, Caine, but I think he had a much warmer heart.”

Elsewhere she wonders why McKay hasn’t received more award nominations for his performance in Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles. But if even his interviewer can’t tell the difference between Caine and Kane, maybe she shouldn’t be so surprised. (If she’s thinking of The Caine Mutiny, the most “labyrinthine” character is probably Lieutenant Commander Philip Francis Queeg, played by Humphrey Bogart in the film; Caine is the name of his ship, and Welles doesn’t appear in that movie at all.) [1/16/10] 1/17 postscript: this finally got corrected two days later.

Read more

Read more