From the Chicago Reader (June 30, 2000). — J.R.

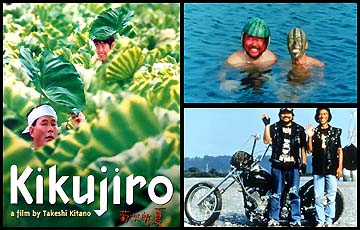

Kikujiro

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Takeshi Kitano

With Beat Takeshi (Kitano), Yusuke Sekiguchi, Kayoko Kishimoto, Yuko Daike, and Kazuko Yoshiyuiki.

I’m finally starting to understand Takeshi Kitano’s movies, though given that his specialty seems to be a mixture of violence, slapstick, and sentimentality, I’m not sure I’ll ever be a convert. Still, I found Kikujiro (1999) — his eighth feature, showing this week at the Music Box — much more affecting than the other three features I’ve seen.

One of the fascinating things about Kikujiro, which has virtually no violence, is that it seems both more mainstream and more experimental in form than the other Kitano movies I’ve seen. It changes style so often that it all but eliminates narrative. It’s divided into sections like a photo album, with photos and captions doubling as chapter headings. It has intricately choreographed expressionist dream sequences, extended gags in extreme long shot that all but convert the main characters into balls ricocheting through pinball machines, and absurd physical gags in medium shot (e.g., the hero tries to swim) that take the form of frozen tableaux and provoke blank stares from other characters. It’s full of strange flights of fancy that come out of nowhere and go nowhere. And along with the laughs, it creates a sense of loss so strong and grievous that this feeling may stick with you for days. Yes, it’s sentimental, but it’s also highly atypical and downright weird. And it’s been haunting me ever since I saw it a year ago at the Locarno film festival.

A statement by the writer-director-editor-star suggests that it’s supposed to be and do all of the above: “After Fireworks, I couldn’t help feeling that my films were being stereotyped: ‘gangster, violence, life and death.’ It became difficult for me to identify with them. So I decided to try and make a film no one would expect from me. To tell the truth, the story of this film belongs to a genre which is outside my specialty. But I decided to make this film because it would be a challenge for me to cope with this ordinary story and try to make it my very own through my direction, and I tried a lot of experiments with imagery. I think it ended up being a very strange film with my trademark all over it. I hope to continue upsetting people’s expectations in a positive way.”

Generic expectations aside, Kitano’s reputation in Japan is based on far more than what he’s done as a film director. As a comic performer, he’s been around for a quarter of a century, having started out as half of a comic duo known as the Two Beats (playing Beat Takeshi — a stage name he still uses as an actor — alongside Beat Kiyoshi). He evolved into a TV personality in the early 80s and in recent years has been appearing weekly on no less than eight or nine programs, which range from sitcoms to game shows. He didn’t begin directing until 1989. (When I was in Tokyo last December, it took only a bit of channel surfing to find him.) Somewhat abrasive and even abusive in manner, he probably shares as many traits with Groucho Marx as he does with Buster Keaton, and poker-faced impassivity has also long been part of his style and persona — something that’s only emphasized by the paralysis in portions of his face, a consequence of a traffic accident several years ago.

I rarely find Kitano as funny as I think I’m supposed to, which makes me wonder if this is because of cultural differences in how we relate to tragedy and comedy. At Locarno last summer, I saw two recent documentary features about him. One of them, Makoto Shinozaki’s Jam Session — a standard “making of” promo about Kikujiro, created by Kitano’s production company — was little more than advertising. The other, Jean-Pierre Limosin’s Takeshi Kitano the Unforeseeable (made for French TV), was helped immeasurably by a sensitive interview conducted by film critic (and now president of Tokyo University) Shigehiko Hasumi, who implicitly treats Kitano as a tragic figure.

French filmmaker Chris Marker recently observed that it rains equally often in the films of Andrei Tarkovsky and Akira Kurosawa. Are Eastern cultures and Russia more comfortable with gloom and tragedy? After all, in Japan suicide is still sometimes seen as a noble and satisfying way of concluding things — a kind of credible Dostoyevskian solution. Hasumi’s approach to Kitano implies that viewing him as some sort of over-the-hill wreck may be a prerequisite for finding him funny. A sense of human wreckage is certainly apparent in Kikujiro, whether or not one laughs at the gags, nearly all of which are suffused with melancholy; I found myself laughing at only about half of them.

Kitano has accumulated all sorts of associations from being on Japanese TV, which obviously makes his films harder for Western viewers to read. The films are also full of personal references. For instance, his former partner Beat Kiyoshi makes a guest appearance in Kikujiro as a security guard at a rural bus shelter whom Kitano gratuitously berates and harasses, but I have no idea whether this scene alludes to some of their old routines. It also can’t be coincidence that this movie opens and closes in the Asakusa district of Tokyo, home to the two leading characters — a nine-year-old boy named Masao (Yusuke Sekiguchi) who lives with his grandmother and Kikujiro (Kitano), the husband of a friend and neighbor of the grandmother — and the place where Kitano spent his own childhood. He has even said that his father — a housepainter and maker of lacquered objects who had many financial ups and downs because he gambled — was the inspiration for the film’s title character.

As suggested earlier, the plot of Kikujiro is so minimal and ambiguous it verges on nonexistent. Masao, a lonely kid, has no father and has never met his mother, who works far away to support him. After he stumbles upon her picture and address, the grandmother’s friend gets Kikujiro to take the boy to see his mother. Instead Kikujiro takes him to the bicycle races and gambles away all the boy’s travel money, but saves him just before he’s molested by a pervert. Then they hitch rides to where Masao’s mother lives, meeting various people en route. Kikujiro spots the mother with another boy and reports back to Masao that she isn’t there; later he hitches a ride to a nearby town and glimpses his own mother in a nursing home without approaching her. Eventually he and Masao return to Asakusa and part company.

Kikujiro is the only developed character, though his background is a bit cloudy. We know nothing about his current or past profession, though some viewers may assume he used to be a yakuza. Masao is more a figure than a character, and we find out even less about his mother. Moreover, the various friends Masao and Kikujiro make on their trip — a writer, a woman juggler, and two bikers — seem to exist only for the purpose of amusing Masao.

The Japanese title of this movie is Kikujiro no natsu, which means “The Summer of Kikujiro,” and central to its singular handling of time is that it has a sort of aimless summerlike drift. Part of what I find so strange and affecting about it is that it goes beyond feeling like “a summer movie” and seems suspended in time, so that the picaresque events could be taking place over three or four days or just as many weeks or months — maybe even years. Kikujiro and Masao have virtually no luggage with them, but that doesn’t prevent them from periodically appearing in different clothes. Furthermore, though most or all of their destinations can be found on maps of Japan and aren’t that far from one another, their cross-country journey feels so mythical that they could be crossing a vast continent.

Indeed, the film feels like an epic, roughly akin to Don Quixote or The Searchers — one that’s infused with a sense of futility and delusion combined with wistful yearning and persistence. The sensation of being caught in an endless loop is reinforced by the main musical theme, by Kitano regular Joe Hisaishi, a piece of treacle featuring piano and orchestra that’s repeated so many times it drills its way into your skull, like one of the elevator-music themes of a comedy by Jacques Tati (or, perhaps closer to the mark, Ryuichi Sakamoto’s main theme for Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, which featured Kitano’s first film performance).

As for the sense of tragedy, I’m hesitant to rely too much on national typecasting. But there are passages about mothers and sons, “passive dependence,” and arrested male development in Ian Buruma’s provocative 1984 book about contemporary Japan, Behind the Mask, that have more to say about the emotions of mother loss in Kikujiro than anything I could add. One fairly sarcastic and brutal paragraph catches Buruma’s overall drift: “The treatment of young children is in a way similar to that of drunks and foreigners. They are not held socially responsible for anything they do or say, for they know no shame. They must be pampered not punished. This wonderful state of grace is one good reason for foreigners to live in Japan and Japanese males to spend much of their non-working hours in a state of inebriation or even, if necessary, to fake it.”

That the movie periodically grinds to a halt so that the juggler, writer, bikers, and title hero can devote their time exclusively to amusing Masao may seem like self-indulgence, but ultimately it points to a traumatic sense of mother loss that no amount of amusement can placate. An experimental feature that keeps shooting off its ideas like an endless row of skyrockets, Kikujiro ultimately conveys this grief with such sustained intensity that it can only leave a scorched path of devastation in its aftermath.