From The Guardian (15 June 2002). — J.R.

I recently found myself arguing with an Australian friend about Tsai Ming-liang’s film What Time Is It There? — a disagreement pointing to contradictory notions about how the world seems to be changing. According to Adrian Martin, with whom I am editing a book on global cinephilia, the film “is all about ‘uncommunicating vessels’: Paris and Taipei, a man and a woman, the living and the dead, unsynchronised time zones, incompatible languages, unreciprocal desires”.

“There is a moment,” he said, “when we need cruel reminders of the realities that disturb any premature fantasies of oneness.”

For me, the film is a triumph of communication and even a kind of togetherness. “It is a Taiwanese-French co-production,” I pointed out, “and Tsai does reveal a certain connectedness, congruence, unity, even hope — not so much on the screen but inside each viewer’s consciousness, where it really counts. There’s even what I’d call a happy ending.”

Actually, we’re both right. From one point of view — mine in this exchange — nationality is already on its way to becoming irrelevant, except as a way for multinational companies to define parts of the global market. For me a major part of the significance of September 11 was its suggestion that the US could be as unsafe as anywhere else — and that even New Yorkers could get a taste of what it has been like to live in Baghdad. Isn’t this related in some way to the Taiwanese hero of Tsai’s film wanting a taste of France after he sells his watch to a young woman who is about to go there, inspiring him to buy a pirated video of François Truffaut’s film The 400 Blows?

Yet part of the fallout of September 11 has been a denial of such common experience — represented most clearly by Bush’s “axis of evil” speech. A comparable kind of denial can be seen in the picture of an American flag affixed to the front door of the building in Chicago where I live, with the caption “September 11 – We Will Not Forget”.

When I mentioned to the neighbour who put up that picture that plenty of non-Americans died in the World Trade Centre apart from terrorists — non-Americans that his poster was inviting us to forget — he refused to discuss the matter. But maybe this is just a symptom of the frightened backlash that usually accompanies any profound change in the world, including the way we think about it. Losing one’s sense of nationality can be frightening to those who depend on such standbys for a sense of their identity.

Though Americans tend to be more culturally landlocked than most of their European counterparts — a handicap that I suspect is shared by other big countries, such as China and Russia — it’s sometimes difficult to distinguish the public’s naivety from that of the pollsters. Consider some of the poll results published in Time magazine last September 24:

Should the US declare war as a result of the attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon?

Yes: 62%

If Congress were to declare war, whom do you think it should declare war against?

Not sure: 61%

Afghanistan/Taliban: 15%

Osama bin Laden: 10%

Terrorists in general: 8%

Palestinians: 4%

Iraq: 4%

Saddam Hussein: 2%

No one – just declare war: 2%

As with movie test marketing, the questions asked play a role in determining the responses, and people are obliged to come up with snap judgments. So it’s telling that the pollsters collapsed Afghanistan and Taliban into the same category, already implying that if the US couldn’t declare war on one of those entities, the other would do just fine.

Having recently collaborated with a Chicago-based Iranian woman on a book about Abbas Kiarostami — and managed to publish an extract simultaneously in a website based in Melbourne and a magazine in Farsi produced in Tehran — I have reasons to believe that some of the “axis of evil” folks and I would have plenty to talk about if our governments allowed us to. Unfortunately, the increasing difficulties imposed on Iranians visiting the US recently prompted Kiarostami to cancel a visit there. But couldn’t these difficulties be traced back to the fact that Iran doesn’t yet figure as a significant market for American products? Maybe I’m just being optimistic, but I suspect that the day that Coke machines are installed in Tehran, Iranian visitors to the US will no longer have to be routinely fingerprinted, as they are now.

Ironically, the movies that are seen by most Iranians these days are pirated, unsubtitled videos of brand new American features, whereas the last thing I heard, neither of Kiarostami’s last two features had even opened in Iran, because of their poor commercial prospects.

I see a profound kinship between the vision of Tsai and that of the late Jacques Tati — a film-maker Tsai has admitted to admiring, and another internationalist whose dreams of social unity are inflected with a strong sense of loneliness. American tourists, German salesmen and French workers may eventually come together in festive accord during the climactic restaurant sequence of Tati’s 1967 film Playtime, but only after a long day of missed connections, bitter misunderstandings and painful isolation, and more accidentally than through any sense of purpose. The hasty way the restaurant was put together in order to open on time leads to various technical disasters, and it’s the shared sense of those comic disasters that leads to the characters finding or discovering one another.

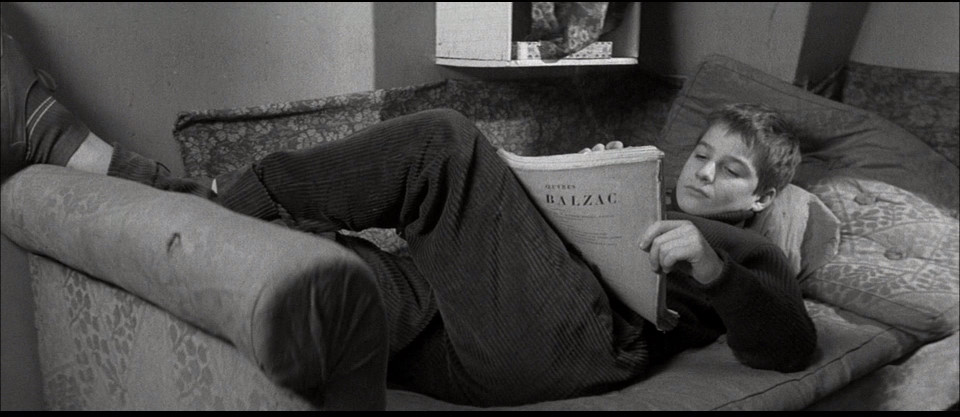

No one really comes together in What Time Is It There? — literally or figuratively, festively or otherwise — yet the whole film is composed of congruences and similarities, visual rhymes and thematic echoes that we are privileged to see, even if the characters remain unaware of them. Thus the heroine who buys the watch from the hero winds up sitting on a bench in a Paris cemetery next to Jean-Pierre Léaud, who 40 or so years earlier was the star of The 400 Blows. Both Tsai and Tati, in other words, seem to be saying that we’d have a lot to say to one another about what we see, feel, and share, if only we knew how to speak.