From Film Comment (January-February 1975). An expanded version of an entry for Richard Roud’s 1980, two-volume Cinema: A Critical Dictionary. (“Dream Masters I,” incidentally, which appeared in the same issue of Film Comment, is devoted to Walt Disney — a much longer essay that can be accessed here.) I was delighted to receive a handwritten letter of thanks from Avery himself sometime after this was published which I still have in one of my scrapbooks. And, for the record, despite my gripes here about the unlikeliness of a Paul Fejos Festival, I did actually attend a Paul Fejos retrospective at the Viennale in 2004, almost 30 years after this was written. — J.R.

Paris, late January, my deadline a week away (later postponed). Tuesday morning, a cable arrives: YES TO DISNEY AND AVERY ARTICLE. Tuesday afternoon, rummaging through pages of frantic notes scribbled while watching eleven Avery cartoons on French TV (a little like reading a book while riding a bicycle), and last December, while seeing a program of eleven more at a local theater (notes in the dark are even less legible). Tuesday night, a return to the second program, inferior to the first but still accessible, more scribbling, giggling, crazies coming out of my eyes and ears. Wednesday, a fresh “mini-festival” of six Droopys comes to town. Willy nilly – or should I say Chilly Willy? – I find myself living inside a Tex Avery cartoon.

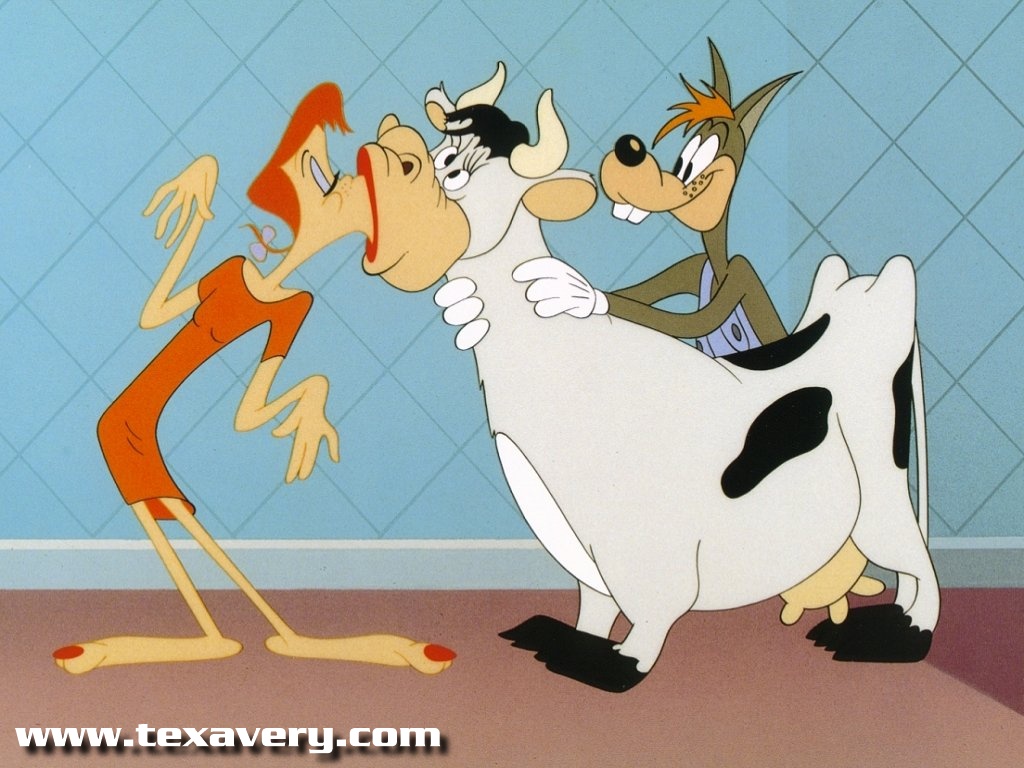

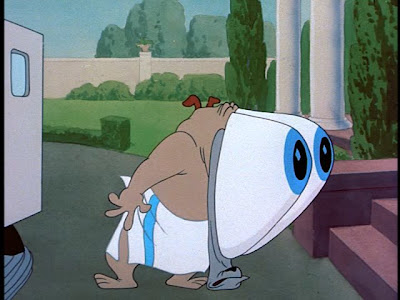

It’s not a bit like Disneyland. If the world of Disney is literally reducible to a funhouse, the very notion of Averyland suggests something much closer to a madhouse — a madhouse where a wise-ass dog named George can strip the skin off a chicken with an axe, revealing black bra and panties underneath (HENPECKED HOBOES, 1946); another dog’s eyes can turn into an American roadmap (COCK-A-DOODLE DOG, 1951); disembodied shoes can perform a layer-peeling striptease à la Buñuel to an enthusiastic burlesque crowd (THE PEACHY COBBLER, 1950); a dog with an Irish accent named Spike can go daffy before your eyes, drop his jaw on the ground like a slab of concrete, rattle his retinas, scream, have his eyes bulge out of his sockets at least a foot or two, and all but slaver at the mouth as he’s finally herded into an ambulance by two men in white coats (DROOPY’S DOUBLE TROUBLE, 1951, an ode to sadomasochistic schizophrenia); cartoon cowboys in a cartoon saloon can watch a real Western on TV (DRAGALONG DROOPY, 1954); a clown in a flea circus can sing “My Darling Clementine” in Droopy’s voice (THE FLEA CIRCUS, 1954); a deranged squirrel can comment on his own cartoon (“Y’know, I like this ending – it’s silly: HAPPY-GO-NUTTY, 1944); a streetcar can make an apparently scheduled stop inside a treetrunk (SCREWBALL SQUIRREL, 1944); Fairy Godmothers can drink martinis, hop on motor scooters, and pursue Don Ameche-type wolves in pretzel-shaped zoot suits (SWINGSHIFT CINDERELLA, 1945); a cat, canary, mouse, and dog can grow larger than skyscrapers (KING SIZE CANARY, 1947); the culprit in a lunatic whodunit can ultimately turn out to be the live-action announcer who introduced you to the cartoon (WHO KILLED WHO?, 1943); or a piano, tractor, tree, and bus can all fall from the sky (BAD LUCK BLACKIE, 1949). (1)

Indeed, Disney and Avery are complementary and contrasting figures in many important respects. If the former has been prodigiously over-exposed, the latter, in recent years, has been just as prodigiously neglected and under-exposed. (Notwithstanding the recent — and very exceptional — Avery programs in Paris and one or two in New York, the very notion of a comprehensive Avery retrospective in this day and age is probably as rarefied and unlikely as a Paul Fejos Festival.)

According to Manny Farber’s useful categories, Disney is white elephant art in all its star-spangled trappings, while Avery, essentially concerned with proving nothing and without an honest pretension to his name, is an important figure in the termite range. Disney’s exclusive focus on the experience of children is neatly balanced by Avery’s preoccupation with peculiarly adult problems and concerns (mainly sex, status, and procuring food)—the voices given to his animals are nearly always grown-up ones.

And if the aim towards “timelessness” in Disney features effectively means that most contemporary references are either accidental or non-consequential (excepting his propaganda films, the Depression uplift offered by THE THREE LITTLE PIGS, and occasional vulgarities in the rest, such as the reference to television at the end of THE SWORD IN THE STONE), the usual tendency of an Avery cartoon, on the contrary, is to be as contemporaneous as possible, so that one finds allusions to — or echoes of — Mae West (as an Indian named Minnie Hot-cha in DUMB HOUNDED (1943), THE LOST WEEKEND (rebaptized THE LOST SQUEAKEND) in KING SIZE CANARY, and even President Truman at the end of DROOPY’S GOOD DEED (1951), appearing offscreen as a not very talented pianist. Inspiration often seems to come from non-cartoon sources: HENPECKED HOBOES (1946), which gives us a smart little dog and a large dumb one who keeps saying things like, “Yeah, George, I’m gonna do goodthis time, George,” harks back to and parodies OF MICE AND MEN, while THE FLEA CIRCUS pays glancing tribute to Busby Berkeley and DROOPY’S DOUBLE TROUBLE reflects P.G. Wodehouse by offering a butler named Jeeves.

One even finds an allusion to Disney in THE PEACHY COBBLER, a side-splitting and fairly devastating parody of some of the Master’s sentimental excesses. We open with an unctuous narrator introducing us to the story proper, his condescending voice drowning in bathos while the camera takes us on a tour of a kitsch Disney cottage: “One cold winter’s night—long, long ago—there lived a poor old shoe cobbler and his wife…” Stifled sob. “All they had to eat was one crust of bread…whole wheat!” Outside, a flock of pathetic little birds are shivering, and when the cobbler gives them a crust out of the Goodness of His Heart, they promptly turn into “happy little shoemaker elves” — slightly demonic versions of characteristic Disney imps.

Avery had reason to be disrespectful: while Disney in his features was generally issuing his benign pronouncements from some imaginary Mount Olympus, Avery and his team of animators and writers (usually Rich Hogan and Heck Allen) were commingling intimately with their casual audience on a strictly meat-and-potatoes level, seven or eight minutes at a time.

Not much worried about good taste or more than a modicum of wholesome family standards, an Avery cartoon could get cheerful laughs out of a hillbilly farmer with a speech impediment “H’llo thar Billy boy boy boy boy boy,” in BILLY BOY, 1954), jokes about Texans reflecting Avery’s background (he was born in Dallas), Cinderella in a boiler suit going to work on the night shift at a wartime munitions factory (SWINGSHIFT CINDERELLA), some arabesques describing sexual desire that defy belief, and many racial and ethnic jokes, each one as transparent and as good-natured as the last. (One glaring exception, in BLITZ WOLF, 1942: apart from Adolf Wolf and “Der Fewer (der better)” scrawled on a truck, one encounters a “No Dogs Allowed” sign with “Dogs” crossed out and replaced by “Japs”.)

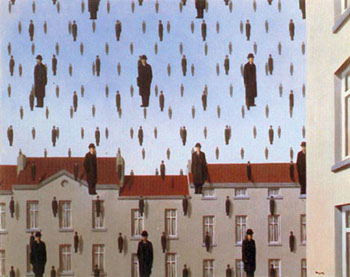

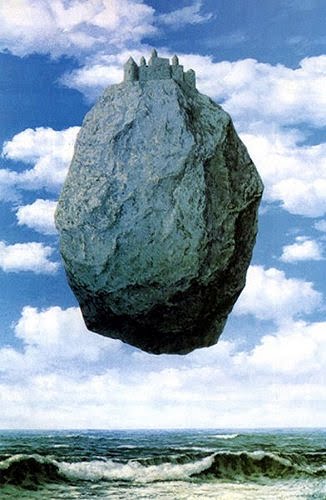

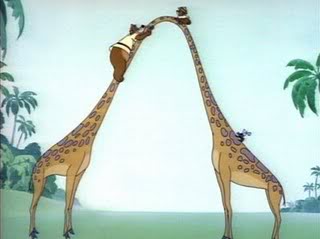

At the same time, his unusually free imagination and taste for surrealist juxtapositions occasionally recapitulate or anticipate a concept—or even an image—from an Ernst or a Magritte: an explosive shower of “defense bonds” in BLITZ WOLF and a Rock of Gibraltar gag in DUMBHOUNDED are striking approximations avant la lettre of Magritte’s Golconde (1953) and The Castle of the Pyrenees (1959), respectively. (John Boorman, by the way, makes a playful allusion to the latter painting in ZARDOZ.) If the Disney factory learned something concrete from Avery, this may have been how to use objects and animals surrealistically. The two headless giraffes connected by their necks and the alligator with a handle in HALF-PINT PIGMY (1947) and the use of objects as creatures in THE CAT THAT HATED PEOPLE (1948) might well have influenced some of the forest beasties in ALICE IN WONDERLAND (1951).

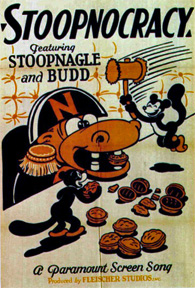

To be sure, if you see as few as half a dozen Averys at a stretch, you’re likely to notice repetitions of gags and certain recurring obsessions (size, insomnia induced by rackets, all kinds of inside references to the cartoon you’re watching), and as many as a dozen together is an experience promoting migraines and nervous exhaustion. Even so, the frantic pace isn’t always sustained by consistent looniness (some of the best of Max Fleischer’s cartoons of the late Twenties and early Thirties — notably KOKO’S EARTH CONTROL and the extraordinarily demented “sing-along” STOOPNOCRACY — are even crazier); the blackout gags in the Droopys of the early Fifties, often isolated like beads on a string, aren’t half as funny as the intricate developments and variations in the earlier ones. But in his prime efforts, Avery can rattle off a complex narrative situation so quickly and efficiently that it’s all one can do to keep abreast of it, and Scott Bradley’s carefully synchronized musical scores — with their generous helpings of Rossini and other classic touchstones — are often remarkable merely by virtue of the fact that they don’t stray behind the action.

Sexual hysteria is a frequent occasion for the speed and frenzy, and LITTLE RURAL RIDING HOOD (1949) is possibly the high point in Avery’s manic sex cycle. Commenting at length on this frightening series, Joe Adamson offers an elegant description of a characteristic sequence in THE SHOOTING OF DAN MCGOO (1945) — a sequence, incidentally, that recalls some of the finer excesses in L’AGE D’OR:

“The ‘lady that’s known as Lou’ gets introduced as the stripper sensation of the joint, and she does one rousing chorus of ‘Put Your Arms Around Me, Wolfie, Hold Me Tight,’ which rouses the wolf no end. His eyes burn straight through the menu in front of him, he smashes his head with a mallet and turns it into a Jack-in-the-Box, he kicks himself behind the ear as part of some perverse notion of a donkey imitation, he slams his head against a nearby post and in the excitement chomps away at the post as if it were a giant carrot, he beats his chair against the table, he picks the table up and beats it against the floor.” (2)

On the other side of the coin is Avery’s flair for ridiculous understatement. The typical utterances of his basset-hound Droopy are usually in this category, but my favorite example comes from his arch-rival in DRAGALONG DROOPY. While Droopy’s herd of sheep move like a battalion of lawn mowers across the wilderness, devouring every spot of green in their path, the camera pans past them to a sign reading

CATTLE COUNTRY

KEEP OUT

THIS MEANS EWE;

then, while Scott Bradley supplies “Home on the Range,” continues past an endless stretch of cows smothering the terrain, a crowded assembly of animals so vast that it makes the last shot of Hitchcock’s THE BIRDS pale by comparison; finally arriving at the rancher sitting lazily on the front porch, surrounded by acres of beef, who turns to us casually and remarks, “Y’know — I raise cattle.”

If the bulk of Avery’s perpetual-motion machines tend to hold up well, this may be because, like the classics of Sennett and Keaton and Chaplin, they are usually irreverent about everything except motion, and because their hysteria is often beautifully formalized (i.e., “orchestrated,” syncopated, balanced, articulated as cleanly and clearly as notes in a scale). According to this latter criterion, I tend to prefer the cartoons that thematically and plastically take off in all directions — SCREWBALL SQUIRREL, LITTLE RURAL RIDING HOOD — to the ones that move relentlessly and predictably towards reductio ad absurdum conclusions, liek KING- SIZE CANARY and HALF-PINT PIGMY. A good example of relatively intricate but unpredictable plotting is the hilarious ROCK-A-BYE BEAR (1952), even though it devotes its entire middle section — successfully — to variations of a single gag.

For anyone suffering from an overdose of Disney piety, one Avery cartoon a day is guaranteed to deliver immediate and lasting relief. Next to the usual sadomasochistic rituals of Tom and Jerry and the increasingly formularized progressions of a Road Runner, the best Avery efforts are explosions of maximal energy and ingenuity within a very confined space — familiar voices leading us, like the descriptions and dialogue in a Kafka tale, through impossible landscapes.

End Notes

1. In all, I’ve seen two dozen Avery cartoons recently (after deducting overlaps), all of them made between 1942 and 1954 at MGM. Consequently I can’t hope to be anything but incomplete here, and Avery’s periods at Warners and Universal – which include his creations and/or developments of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Chilly Willy – have to be omitted. For a full account of Avery’s career, one eagerly awaits Joe Adamson’s Tex Avery, King of Cartoons, scheduled for publication in the near future. In the meantime, check out Adamson’s interview with Avery in Take One, vol. 2, no. 9.

2. “Tex Avery and the Pleasures of the Flesh,” Funnyworld No. 15, Fall 1973.