From the April 28, 2000 issue of the Chicago Reader.

Fun and infuriating in roughly equal proportions, Mike Figgis’s Timecode is an unusually bold experiment for a major studio. Its plot is outlandish and its characters the most overblown parodies this side of Robert Altman. In some respects, it’s even more cockamamy than James Toback’s Black and White and its sensationalist riffs. So you can’t laugh at much of it without feeling either self-satisfied or stupid.

The silliness and the daring of Timecode are often made to seem like opposite sides of the same coin — a kind of cagey self-protection that cheerfully self-destructs to ensure that the movie poses little threat to anyone. Back in the 60s, critic Noël Burch tartly observed that there would always be an 8½ to provide a refuge from the implications of a Last Year at Marienbad. Timecode suggests an unlikely synthesis: a flamboyantly obvious and carnivalesque satire of Tinsel Town and its excesses tied to an open-ended, highly interactive, and somewhat abstract form. It isn’t nearly as good as either predecessor. But it’s an irrefutable triumph of engineering, and it entertained and intrigued me through two separate viewings — though as a view of the human condition it’s astonishingly and depressingly meager.

If memory serves, literary critic James Wood once described Figgis’s Leaving Las Vegas as “total degradation swaddled in fall colors,” and that’s as good an explanation as any of why a filmmaker as likable as Figgis keeps letting me down. As encouraging as it is to see him spinning so many risky projects out of that single hit, none that I’ve seen has measured up to its promise — and none of them has promised more than Timecode.

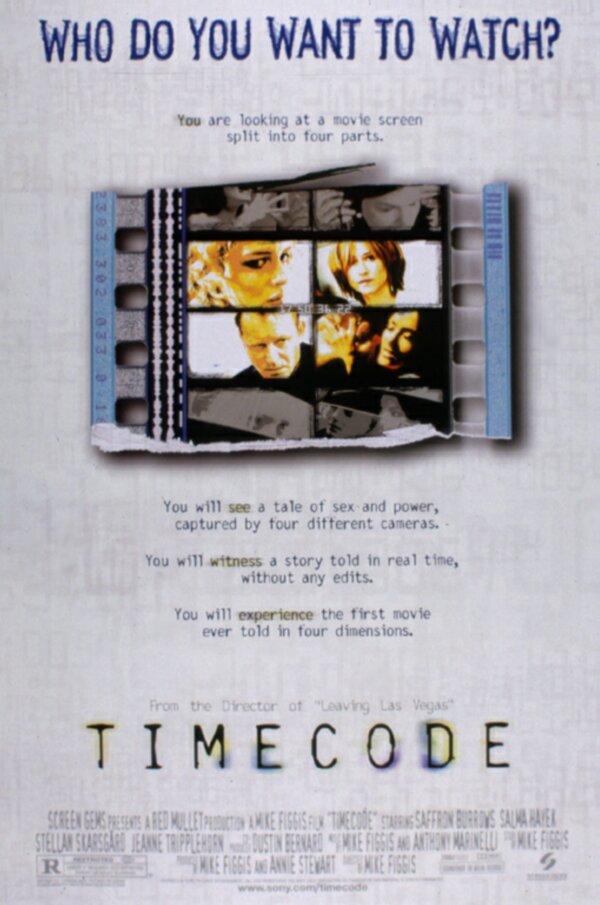

It consists of a grid of four stories that transpire simultaneously during the same 93 minutes. They were shot without a cut by four digital video cameras ranging over a few blocks in Hollywood, and most of the action revolves around an audition for an idiotic-sounding movie and an over-the-top pitch for another movie that bears an obvious resemblance to Timecode. Timecode‘s production company, Red Mullet, or at least a location calling itself that, is where most of the plot unfolds, next door to a real store called Book Soup on Sunset Boulevard. The action is all carefully plotted, and the four cameras are intricately synchronized. But, according to the final credits, the dialogue is improvised by the actors.

The whole thing calls to mind a hyperbolically overdetermined board game with four squares, punctuated by no less than four earthquakes — each one providing a formal marker as well as a sensationalist frisson (and an effective means of coordinating the narrative developments in all four frames). The upper right square, the first to appear on-screen, is occupied by Emma Green (Figgis regular Saffron Burrows), the troubled wife of philandering movie producer Alex Green (Stellan Skarsgard), who tends to occupy the lower right square. Emma recounts a dream to a therapist, walks a few blocks to Red Mullet to see Alex briefly and discuss a planned visit to Tuscany (just in time for earthquake number two), then proceeds to Book Soup, where she meets a blond actress who’s just auditioned at Red Mullet with director Lester Moore (Richard Edson) for a part in Bitch From Louisiana; eventually the two women walk to the blond’s apartment for some tentative love play.

The upper left square is commandeered by wealthy Lauren Hathaway (Jeanne Tripplehorn), who surreptitiously lets air out of one of the tires of a car belonging to her young lover Rose (Salma Hayek), an aspiring actress, so that she can give Rose a lift to the Red Mullet audition. As they ride together in Lauren’s limo, Lauren slips a microphone into Rose’s purse so that she can track her infidelities. After dropping Rose off, Lauren insists on waiting for her in the limo, then proceeds to eavesdrop on her.

The bottom two squares are occupied mainly by Rose and Alex in different corners of Red Mullet, making a date on their cell phones for a sexual tryst behind the screen in a room where executives are watching rushes; when they get together, we see two separate views of them grappling in front of the same screen images, while Lauren listens in at upper left and Emma gets cruised by the actress in Book Soup at upper right. Eventually things get even more melodramatically contrived and climactic, so that someone gets shot shortly before earthquake number four hits — but not until after Rose, while leaving the ladies’ room, gets “discovered” and then auditioned by Lester, and Alex sits down with other executives (including Holly Hunter) to hear a young European woman named Ana (Mia Maestro), represented by an oily agent (Kyle MacLachlan), pitch a movie just like Timecode, to the strains of music performed live on a keyboard by her boyfriend, sometimes with his rap interpolations.

If you think all this sounds a mite precious, you ain’t heard nothing yet. The pitch itself manages to cite collage, montage, Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus, Russian formalism, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Guy Debord, Erwin Piscator, Jorge Luis Borges, and Hanns Eisler — all in the space of a few sound bites. Alex promptly breaks into giggles and calls this “the most pretentious crap I’ve ever heard,” signaling the audience to laugh along with him. The significant thing about Ana’s absurdly parodic patter, as Figgis admitted when speaking to a Chicago audience last week, is that he actually believes it at the same time he feels obliged to ridicule it (which also means he must have written it). It’s just the kind of conflict Robert Altman has constructed some of his worst moments around — a mockery of his own impulses toward seriousness (apart from a few unmockable standbys, such as the American flag in the last sequence of Nashville) that corresponds to a flattening of certain characters into grotesque stereotypes.

Ironically, one name is conspicuously missing from Ana’s intellectual hit parade — André Bazin, the film theorist who celebrated the realism and the freedom of the spectator that theoretically derive from deep focus and an absence of montage, principally in films by Jean Renoir, Orson Welles, and William Wyler. Bazin’s notion of realism, predicated on the premise that the camera doesn’t lie, has been challenged by digital technology, because the ability to alter a film image a pixel at a time means there’s no longer any necessary equivalence between what a camera records and what we wind up seeing. We’ve arguably lost a great deal as a consequence. Jacques Rivette’s dazzling 750-minute Out 1 (1971) — an eight-part serial in 16-millimeter still unscreened in this country that remains one of the boldest experiments in film narrative ever attempted — was conceived as a kind of parody of Bazin’s ideas in its deft mixture of documentary and fiction, its improvising actors working through a dense plot built around real and imagined conspiracies, and even its extended takes, one of which lasts 45 minutes as it records a theater group’s exercise.

Though he hasn’t seen Out 1, Figgis does seem aware of some of the Bazinian issues it raises. Unfortunately, the defeatist and postmodernist notion of capitalism absorbing and thereby defeating every attempt at revolutionary change — another prominent theme in Ana’s sales pitch — seems much more relevant to the limitations of Timecode as an experimental undertaking. It’s too bad that Figgis’s previous feature — a version of Strindberg’s Miss Julie that uses split-screen techniques — has opened locally only in the suburbs and wasn’t screened for the Chicago press, because Figgis has said that, along with one of his much earlier forays as a stage director, it shows us where much of Timecode comes from. (In terms of film precedents, he has also cited Napoleon and Woodstock, but not The Chelsea Girls or Forty Deuce.) But attempting to connect this film with film history in general, which Ana’s pitch obliges us to do, only emphasizes what’s shallow about it.

As shallow as Ana’s pitch is, I’d gladly choose it over the first half dozen lines of advertising copy on this movie’s official Web site, which show the logical result of Figgis’s defeatism: “Technology has arrived / Digital video has arrived / For the first time, a film shot in real time / It’s time to move forward / From the director of Leaving Las Vegas / A story that could only be told in four dimensions.” All of which suggests a theorist-turned-publicist hatched in Bill Gates’s brain.

After all, the notion that innovative ideas grow directly out of new technology sounds like another sales pitch. A more realistic assessment might point out that the overall sterility of most contemporary commercial filmmaking can be traced in part to the ease of editing made possible by the Avid, a digital editing machine — because the ability to make many more edits becomes a curse if the choices aren’t controlled by an artistic or ideological agenda. By and large, all meaningful artistic innovation entails a desire to express new content; dressing up old content with new technology merely entails selling more equipment. So the fact that Figgis has shot a movie without cuts means little if he doesn’t have an interesting reason for making a movie in real time. (By contrast, Robert Frank’s one-take documentary video One Hour, shot in 1990 in New York City’s Tribeca, is immeasurably more exciting and adventurous as it navigates among various public and private spaces.)

The most interesting experimental element in Timecode is the way the sound mix inflects the storytelling, including the dialogue: we almost never hear the sound of all four images at once, and we rarely hear more than one sound track with the same intensity — so the decisions made by Figgis on this level become crucial in shaping our overall experience. When speaking here last week, he noted that in some other American cities, he’s been previewing the movie with a live and improvised sound mix, and I suspect that seeing and hearing it that way, in concert form, could easily make it more interesting — especially if one were able to see it more than once. (He shot the movie 15 consecutive times with four digital cameras, operating the one that appears on the bottom right himself; and the “final” version of the film is the last one shot, though he plans to release the first as well as the 15th on DVD.)

A few more glancing formal pleasures can be found here: a brief congruence early on when all four squares simultaneously feature close-ups of eyes, for instance, or a moment shortly after the second earthquake when the oily agent, who’s speaking to Alex on a cell phone, is sighted through the rear window of Lauren’s limo. The problem is that none of the characters in this movie is able to grow beyond the confines of its self-satisfied jokes, so it becomes all too easy to view them as strictly formal patterns.

No such problem is posed by Alexei Guerman’s brilliant, grim, and madly intractable Khroustaliov, My Car! (1998), playing this week at Facets Multimedia, about which I’d prefer to say as little as possible — in part because the film says and does so much I couldn’t begin to know how to paraphrase its discourse or activities. Like some Fellini films, it’s autobiographically based yet phantasmagoric in feeling. Most of it is set in February 1953, during the last gasp of Stalin’s rule, and focuses on a brain surgeon/former alcoholic/Red Army general sent to the gulag because he has Jewish relatives. At least I think that’s why he’s sent; the paranoid atmosphere keeps everything fairly uncertain and sinister, and my second look at the film left me no wiser about the plot than my first.

The film was started before the collapse of the Soviet Union and completed only after it became a French-Russian production. The highly complex and deliriously articulated mise en scène is built around a subjective camera that most often moves through cluttered and claustrophobic interiors and snowy exteriors, with a lot of activity organized around people moving laterally in and out of the frame in the foreground. In many ways its visual style resembles that of Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons, though the details are much too sordid and nightmarish to evoke nostalgia. Composed mainly in long takes — none of them close to 93 minutes — on high-contrast black-and-white film, Khroustaliov, My Car! could never have a Web site or a T-shirt, much less a sales pitch, because the experience of watching it eludes commodification on every level. Technically I find it a more impressive achievement than Time Code, because it’s a richly detailed period film, and because it seems created out of a deep personal necessity that borders on the demonically obsessional. As unwieldy as its title, it’s about something other than the equipment used to make it.