From the Chicago Reader (June 6, 2003). — J.R.

Monday Morning

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Otar Iosseliani

With Jacques Bidou, Anne Kravz-Tarnavsky, Narda Blanchet, Radslav Kinski, Arrigo Mozzo, and Iosseliani.

Chihwaseon

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Im Kwon-taek

Written by Kim Yong-oak and Im

With Choi Min-sik, Han Myung-goo, Yoo Ho-jung, Ahn Sung-ki, Kim Yeo-jin, and Son Yae-jin.

I haven’t attended the Cannes film festival in five years, but one thing that keeps it fascinating from a distance is the ideological tension that gets exposed there. The Americans display a sense of entitlement, which tends to irritate representatives of other countries. And the conflict is played out in the form of rants from both sides about what’s shown in competition and what wins prizes.

The usual hyperbolic level of the discourse was exacerbated this year by the war in Iraq. American critics — especially in the trade press, which tends to have the highest profile at Cannes — expressed the same sort of disdain for French critics as other American journalists had for French politicians just before and after the invasion. In turn the French and British media bashed Hollywood studios and their flacks, just as they’d bashed the U.S. government and its flacks before and during the war.

All this hysteria can produce a kind of rude honesty about philosophical differences between American and European critics. In maintaining that either the world or the world of cinema is going to hell in a handbasket, they reveal what they’d like to see. “In the glory days of Cannes,” Roger Ebert wrote in the Sun-Times on May 21, “style was Fellini’s gracefully moving camera and shots that seemed to sing. Or audacious experiments by Quentin Tarantino, Spike Lee and the Coen brothers. Or the freshness of the New Wave. Or the audacity of Fassbinder and the vision of Kurosawa.

“Then along came Angelopoulos from Greece and Kiarostami from Iran, with their fashionably dead films in which shots last forever, and grim middle-aged men with mustaches sit and look and think and smoke and think and look and sit and smoke and shout and drive around and smoke until finally there is a closing shot that lasts forever and has no point.”

It’s hard to know what mustache- and smoke-filled films Ebert had in mind. To the best of my knowledge, he’s seen only two Kiarostami films, Taste of Cherry and 10, neither of which has a character who smokes (with or without a mustache) and only one of which has a driver who’s middle-aged or male. And Ebert’s Web site contains a review of only one Angelopoulos film, Ulysses’ Gaze, a feature whose clean-shaven hero, Harvey Keitel, travels mainly by taxi and boat. Moreover, many Angelopoulos and Kiarostami films — Days of ’36, The Travelling Players, The Traveler, Close-up, The Wind Will Carry Us — are packed with events. Yet Ebert clearly sees eventlessness taking over film art like a fungus.

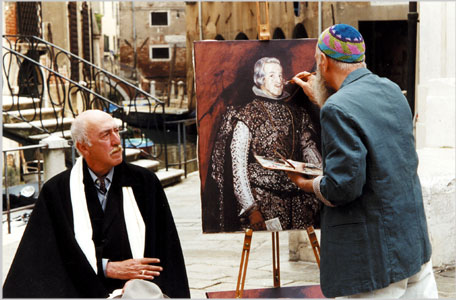

It isn’t hard to find examples of the kind of films he’s ridiculing by other directors. One of them is Otar Iosseliani’s Monday Morning, showing at Facets Cinematheque this weekend. Winner of a best-director prize at Berlin last year, it has a grim and dull middle-aged hero who smokes a lot, thinks, drives, sits, walks, and looks, often in long takes, and very little else happens in the usual sense over the course of two hours — apart from his leaving his boring job at a toxic chemical plant and his family in rural France to go to Venice and eventually returning. Furthermore, there’s not much to look at that’s decorous (i.e., attractive and upper-crust, like the restaurant in My Dinner With Andre) — that might be another failing in Ebert’s mind. None of the shots sing and most of the settings, at least those in France, are drab and uninviting. To make matters worse, the only time we are shown decorous surroundings — when the hero looks up an aristocratic friend of his father’s at his plush digs in Venice — the point is to ridicule not celebrate them. (Iosseliani himself plays this aristocrat, adding an edge to the ridicule.)

Like Kiarostami and Angelopoulos, Iosseliani has a taste for uninflected long and medium shots and prefers to avoid close-ups, a stylistic choice that tends to place a large part of the burden of a film’s meaning on the observations and interpretations of the audience. In this respect, superficially at least, Iosseliani is even closer to Jacques Tati, whose “inventions” and invitations to the viewer depend almost entirely on the viewer’s observations. But as Ronnie Scheib — who reviewed Monday Morning for the Reader when it showed at the Chicago International Film Festival last fall, declaring it a masterpiece — aptly noted, “Though often compared to Tati, Iosseliani depends less on a central comic actor than on limpid compositions of collective portraiture, like the social canvases of Bunuel or early Jean Renoir.” Monday Morning‘s central character — whom the film periodically and distractingly drops to concentrate on other characters — complicates this portraiture without negating it.

The initial impression that nothing is happening in a typical Iosseliani (or Kiarostami) shot is actually an indication that we’re being asked to accept that what we generally define as a filmic event is being redefined — and redefined to show us more, not less. If we balk at such an invitation — as I do to some extent in Monday Morning but don’t in Kiarostami’s The Wind Will Carry Us — this may have more to do with the film’s content than with its style, at least if we perceive that content within a wider conceptual frame. In both cases the activities in a remote village are the main bill of fare, and therefore the issue for the viewer is partly a matter of the philosophical overview of this content.

In The Wind Will Carry Us this has to do with the different perceptions the villagers and “media people” have of their immediate surroundings, which are the same — a contrast that’s implicit, albeit constant, because only one media person ever appears on-screen, and he figures mainly as the viewer’s surrogate, while the perceptions of the villagers are suggested mainly by what he fails to perceive. In Iosseliani’s case there’s no such contrast, the only subject being the various ways the hero and his family and acquaintances cope with a relatively dull and empty existence, inflected by such irritations as the No Smoking signs that the hero, Vincent (Jacques Bidou), passes every time he shows up for work. From the visible evidence, the only pleasurable activities in this existence are painting, performing music, hang gliding, smoking, and getting drunk, especially the last two.

Iosseliani, who was born in the Soviet republic of Georgia, has said, “I made a comedy about the unhappiness of being obligated to obey the rules of this world.” On the subject of smoking he’s more explicit: “In Monday Morning, there is the most elementary prohibition — it is forbidden to smoke everywhere. This prohibition enrages me. The Europeans went to the Americas and brought back tobacco. They made an industry of tobacco. They made an enormous amount of money. The result is that most of the continents began to smoke like locomotives. Then all of a sudden: Stop. Smoking is forbidden. All while continuing to make money. That’s revolting. Especially when you think that it’s the USA that supplies us with different types of Marlboro. It’s the country that has the network of factories that don’t stop supplying us with cigarettes. And it’s the country where it’s forbidden to smoke in restaurants.”

On the subject of drinking, I’ll note that Iosseliani and I have a Parisian friend in common, and several years ago the two of us were camping out in this friend’s flat while he was away. Iosseliani cordially offered me a shot of vodka for breakfast and was clearly insulted when I declined.

Iosseliani’s liking for cigarettes and vodka creates amusing and even fruitful moments in Monday Morning. But I question how rich a view of the good life these things offer in comparison to village architecture, landscapes, animals, insects, and poetry — all of which get similarly appreciative play in The Wind Will Carry Us. That Iosseliani mocks his role as artist-seer by playing the pompous and phony aristocrat in Monday Morning only confirms that his view of pleasure, including art, is fairly jaundiced.

If one were looking for the precise opposite of Monday Morning, Im Kwon-taek’s Chihwaseon — a South Korean biopic about 19th-century painter Jang Seung-up, winner of the best-director prize at Cannes last year and playing this week at the Music Box — could fill the bill quite nicely. As fast as Monday Morning is slow, it rushes through the life of its subject in nimble leaps and bounds, concentrating on the livelier and more spectacular parts and avoiding the dull historical and biographical stretches. Every instant radiates significance. Though Jang Seung-up was a commoner, his fate as an artist was so tied to wealthy patrons that we wind up seeing as much of their worlds as we do of his. Because his specialty was landscapes, we’re treated to many handsome natural settings and many lovely paintings — some while they’re being painted, which allows their beauty to take shape before our eyes. Moreover, because the painter is shown as a raucous alcoholic, womanizer, and social rebel who tends to gruffly defy even his supporters — a kind of East Asian Charles Mingus — his behavior has a slam-bang style that’s entirely in keeping with the crisp and aggressive storytelling.

When I first saw Chihwaseon three months ago, the staccato editing, the speed of the narrative, and the fleeting beauty of certain shots persuaded me I was watching a full-blown masterpiece, something roughly comparable to Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1946 Utamaro and His Five Women. I’d been primed for such a conclusion by the pictorial beauty of two of Im’s earlier period features, Fly High Run Far (1991) and Chunhyang (2000), and by his status as the most respected living Korean filmmaker. And the elliptical manner of the storytelling, which invited me to fill in the missing pieces, led me to believe that the film was saying a lot of things about art.

After a second look, I’m less sure about these impressions, and I’m inclined to think the film may be saying more about class than about art. I also wonder whether the lively and seductive surface is a kind of smoke screen, distracting viewers from the sketchiness of the content. For very little is known about Jang Seung-up; as Im admits in an interview, “The fact that he liked women, booze, and that he was a genius were all that were known about him.” Indeed, the film’s concluding title — explaining that nothing at all is known about his final years — may be its most poignant and affecting moment. After an apparent surfeit of details, we’re suddenly suspended over a void — a sudden, unexpected reticence that gains our respect.

The point I’m trying to make about Monday Morning and Chihwaseon in relation to Ebert’s lament is that a lot more than speed, narrative content, and apparent meaning shapes our predilections when it comes to film art. I’ve seen Monday Morning only once and am in no rush to see it again, yet I suspect it would look better rather than worse if I did. This is mainly because its long, “pointless” shots allow my imagination more room than all the pithy, meaningful, and singing shots in Chihwaseon — which rush me past most opportunities to ponder, leaving me with less, not more.