From In These Times (March 31, 1997). Some of the material here wound up in my book Movie Wars, published in 2000. -– J.R.

There’s a new kind of factoid at large in this country on the subject of foreign films. At a time when Americans have retreated into cultural insularity and isolationism as seldom before, one repeatedly hears the same list of reasons for foreign films’ near invisibility in this country: The quality of world cinema is at an all-time low; Americans can no longer bear to sit through movies with subtitles; Americans went to European movies in the past only in order to see bare skin, and ever since American movies became sexually explicit, this market has drastically dwindled; and there are no exciting new movements in world cinema to compare with Italian neorealism, the French New Wave, Brazilian cinema novo or the new German cinema. That none of these claims (with the arguable exception of the second) is even remotely true shouldn’t be too surprising, because the “experts” who give voice to them typically define their expertise institutionally:

If the statement is being made in the New York Times, Esquire or The New Yorker, then it must have some factual basis. The prevailing philosophy seems to be out of sight, out of mind — and anything not for sale within our borders is by definition out of sight. Practically speaking, this means that the only opinions that matter are not those of these critics — Susan Sontag, New York magazine’s David Denby and the New Yorker‘s Terrence Rafferty are three recent examples — but those of the people who acquire films for major U.S. distributors.

To be fair, Sontag — unlike Denby and Rafferty — attends a certain number of overseas film festivals, and therefore has some basis for her laments. But missing from her arguments in “The Decay of Cinema,” an essay that appeared in the New York Times Sunday Magazine Last February, are such recent and important names as Souleymane Cissé, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Abbas Kiarostami, Stanley Kwan, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Béla Tarr, and Edward Yang. These figures, who all have substantial reputations abroad, have almost no profile at all in the United States simply because no big-time distributor has chosen to invest large sums of money in promoting them. (The small but courageous distributor Cinema Parallel has given some limited play to Tarr’s stunning, seven-hour Sátántangó, with only token recognition in the press.)

Significantly, the original version of Sontag’s essay, published in many other countries and languages, mentioned Béla Tarr twice. A Times editor omitted both references, along with allusions to several other foreign directors — Theo Angelopoulos, Miklós Jancsó, Alexander Kluge, Nanni Moretti, Krzysztof Zanussi –who have not found much favor in recent years with Times reviewers or U.S. distributors. Conversely, the Times version of Sontag’s essay includes references to Francis Ford Coppola and Paul Schrader that weren’t in the original version. (They’re cited as “artistically ambitious American directors” who haven’t been able “to work at their best level” because of “the lowering of expectations for quality and the inflation of expectations for profit” in this country.) In other words, to make it into the mainstream media, even an article on Hollywood’s ruinous effect on world cinema has to reproduce the very phenomenon it decries.

Academic film study would ideally call attention to such artists as those excised from Sontag’s list and those on mine. But it is hamstrung by the notion infecting numerous academic disciplines that canons are intrinsically wrong. This belief has hardly made canons disappear — inevitably, a few films are studied far more often than the rest — but it has made it impossible to intelligently expand and update them. So the canons that still function in film schools are 10 years to 20 years out of date.

This tunnel-vision reckoning misses nor only a lot of important movies, but also an historical and economic understanding of our current plight. America was introduced to foreign films largely by two Roberto Rossellini masterpieces of the mid-’40s, Open City and Paisan, each of which grossed close to a million dollars — an enormous sum in those days — and neither of which, pace Terrence Rafferty, qualified as a skin flick. By the late ’60s, there were more than 1,000 art theaters in this country showing foreign films. This success story had less to do with the quality of foreign films, however, than with the enforcement of certain antitrust laws.

It all started n 1938 when the U.S. government filed an antitrust action against Paramount Pictures for its monopoly of movie theaters, arguing that a studio that controlled theaters to show its own product was exercising an unfair advantage over smaller, independent exhibitors. This suit created new space for independent theaters. By the early ’50s, these theaters — which usually rented films for a flat rental fee rather than for a percentage of ticket sales – were flourishing in the more open market. These were the theaters that showed foreign pictures, revivals and eventually midnight movies — three forms of exhibition that grant programmers a lot of creative freedom. Sontag waxes nostalgic about the movies made in the ’50s, but she forgets about the existence of theaters that could show them.

What happened to those theaters? When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, he stopped enforcing the antitrust laws, and no subsequent administration has started up this process again. Corporate control of theaters matched by corporate control of the media yields a playing field where Hollywood is literally the only game in town. This may not seem apparent at first if one factors in the handful of “blockbuster” foreign films, most of them in English, handled by Miramax — the largest U.S.. distributor of foreign films and a Disney subsidiary famous for its zeal in recuttingsome pictures and burying others. But smaller distributors of foreign films have to depend on independent first-run theaters like the Angelika in New York and the Music Box in Chicago, and there are painfully few of these left today. The simple reason why more foreign pictures don’t play in this country is that there aren’t enough independent theaters left to show them.

Have foreign pictures really declined in quality? That’s a pretty sweeping generalization to make about all the movies produced outside this country, especially on the basis of the small fraction any individual is able to see. Based on the half dozen or so international festivals that I attend annually –- as well as the hundred or so additional titles I see as a member of the New York Film Festival’s selection committee – I can’t see any reason for making such a claim.

Taiwanese filmmaking, for instance, is going through an especially rich period. Taiwan spent most of the past century under martial law; since l987,democracy has enabled its filmmakers to reflect on their own individual and collective history for the first time. This freedom has also led irresistibly to a fresh look at today — a capacity to view the present in historical perspective that parallels some of the achievements of the Italian neorealists and the French New Wave directors without in any way duplicating them.

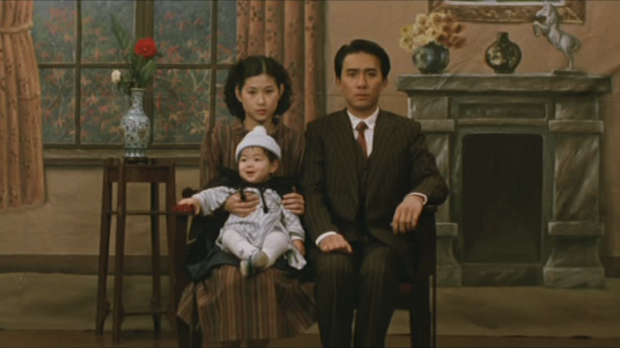

This development can be clearly seen in the work of both Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang. Hou’s masterful trilogy about Taiwan in the 20th century couples each period covered with a separate art form. City of Sadness (1939) explores still photography and the four years between the end of World War II and the retreat of the Kuomintang to Taiwan. The Puppet Master (1993) encompasses the first 36 years in the life of puppet master and stage actor Li Tienlu (1909-1945). The trilogy concludes with Good Men, Good Women (1995), which takes on the cinema itself, harshly contrasting the political convictions of an anti-Japanese guerrilla in China in the ’40s with those of a film actress about to play her in the present. Hou followed the trilogy with last year’s devastating Goodbye South, Goodbye, a contemporary tale about entrepreneurial gangsters in Taiwan’s backwaters that vividly evokes the rootless horror of what business is currently doing — physically, culturally and emotionally — to Asia.

This progression is closely paralleled by Edward Yang’s development. His nearly four-hour A Brighter Summer Day (1991) is arguably the greatest Taiwanese movie to date, charting events in the early ’50s that led to the murder of a 14-year-old girl by her former boyfriend and classmate, and dealing with such subjects as the anti-communist White Terror, rival boys’ gangs, and the impact of Elvis Presley on Taiwanese youth. Yang’s two subsequent features, A Confucian Confusion (1994) and Mahjong (1996) are both ambitious, multi-character mosaics about the impact of capitalism on Taiwanese life and culture. But none of Yang’s or Hou’s films has acquired a U.S. distributor.

Much as Hou and Yang dominate the Taiwanese New Wave, Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbafare the two outstanding masters of Iranian cinema. Both of them, hampered at times by constraints at home, enjoy wide recognition elsewhere, especially at film festivals. In 1969, Kiarostami, a middle-class director of TV commercials, set up a film unit at the state-run arts and education organizationlaunched by the shah’s wife and known today as the Kanun, which has produced nearly all his films. His 10 or so shorts — about half his output — are mainly comic lessons for children that are both formally playful and conceptually inventive, and comparable to some of the best experimental filmmaking done anywhere. His recent features include a singular documentary about schoolchildren and the trial of an imposter who impersonated Makhmalbaf (Homework and Close-Up, respectively, both 1990), and an extraordinary trilogy set in a village in northern Iran that, after the first feature, suffered aserious earthquake (Where Is My Friend’s House? (1987), Life and Nothing More (1992), and Through the Olive Trees (1995). Combining elements of fiction and documentary, and concentrating on the complex interchanges between filmmakers and ordinary people, Kiarostami’s work in the ’90s conveys a cosmic and often comic view of everyday life that arguably places him on a level with Jean Renoir, Satyajit Ray, Akira Kurosawa and the best of the Italian neorealists. But in this country, he’s known only as the screenwriter of Jafar Panahi’s The White Balloon.

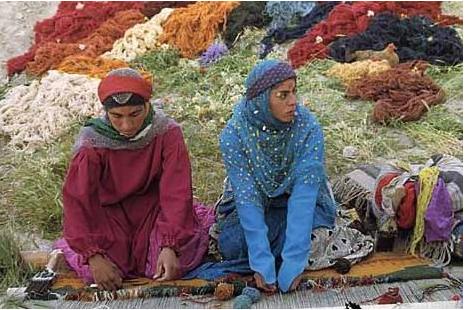

Far more eclectic and mercurial than Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf — a working-class political activist who was imprisoned by the shah for five years when he was 17 (an event depicted in his latest feature, A Moment of Innocence) — started making films in 1982. I’ve seen nine of his 14 features, and no two are alike. From the potent neorealism of The Peddler (1,986) to the troubled expressionism of The Marriage of the Blessed (1983), the quirky modernism of The Actor (1992) and the colorful magical realism of Gabbeh (1995), Makhmalbaf has remained a restless explorer who has had many brushes with Iranian censors — at least three of his features have been banned outright — while remaining something of a populist hero among Iranian filmgoers. (Kiarostami, by contrast, is regarded by many of his compatriots more ambivalently, in part because he was “discovered” by Europeans and is felt by some to cater to Western tastes.) While it would oversimplify matters to call him the Iranian Scorsese, Makhmalbaf’s troubled and ambiguous relationship to his Islamic background does suggest a few parallels to Scorsese’s Catholicism. More recently, in Salaam Cinema (1994) and A Moment of Innocence, his reflections on his own status as a filmmaker suggest that he has been marked by Kiarostami, but has fully integrated this influence into his own humanist vision.

But almost all these developments will remain unremarked in the American mainstream. Yes, Miramax did pick up Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees, but it then handled the film so dismissively that it was impossible for word about Kiarostami’s sublime cinema to get out. The New Yorker didn’t even bother to come up with a capsule review for the film (or, for that matter, for André Téchiné‘s Thieves, arguably the major French feature of 19961. One can safely bet that Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf, Hou, Yang and the others on my short list, all missing from the third edition of David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema, won’t make it into the fourth edition either.

Hollywood has a vested interest in keeping things exactly as they are. Declaring the death of world cinema is just another ruse for keeping its monopoly alive. Some of its co-conspirators are even more ingenious: Those who made it to Special Effects, a 40-minute Omnimax infomercial for the release of the “special edition” Star Wars trilogy will have noticed in an opening title that it received major funding from the National Science Foundation. Nice to see our tax dollars going to help George Lucas pay the rent. And nice to see the New York Times looking out for its readers by keeping Béla Tarr and all those other unfamiliar names out of Sontag’s prose.