I no longer recall who asked me to write this or why, but I estimate that I must have written it in late 1997 or early 1998, and probably for some foreign publication. I’m happy to see that much of what I wrote, especially about the Times, is now out of date. — J.R.

The New York Film Festival is held every fall, usually in late September and early October. Unlike every other major film festival that comes to mind, it features relatively few programs, less than thirty — a concentration that allows the festival to give more of its attention to each film it shows than many others do. (As a rule, every feature is accorded a press conference, and public dialogues with the filmmaker usually follow each screening.) This often means that many of the foreign and independent films that show at the festival have a more substantial commercial launching than most of those that don’t. (It’s different for Hollywood films, which already have enormous promotional budgets at their disposal. In fact, most mainstream American releases aren’t even submitted, in part because the studios are afraid that a New York Film Festival showing might handicap a movie with the stigma of “art film”.)

The pre-eminence of the New York Film festival in the U.S. is mainly a function of the pre-eminence of New York in what it has to offer in world cinema all year around — and the power of New York film critics over most others in the print media. Unfortunately, this power isn’t always matched by sophistication or scholarship. The most knowledgeable film critics in New York, such as the New York Daily News‘s Dave Kehr and the Village Voice‘s J. Hoberman, are considerably less prominent and influential than the critics of the New York Times, New York, and the New Yorker, and though the former offers extensive (if relatively uninformed) festival coverage, the latter two magazines offer no festival coverage at all. Furthermore, all three of these publications tend to regard world cinema important only when it impinges on American pop culture, and even then limited to only a few key countries — which usually means that in-depth commentary on festival films either appears only months later in fringe magazines or not at all. Moreover, the Times‘ national power makes the festival “a gatekeeper in spite of itself,” as former committee member Stuart Klawans points out. Typically, a negative Times review will result in hundreds of festival tickets being returned for refunds; in the case of Antonioni’s Identificazione di una donna, it even led to a U.S. distributor dropping the film. (Sixteen years later, the film has still never opened here.)

To arrive at its twenty-odd programs out of thousand of submitted films, the Film Society of Lincoln Center, which runs the festival, spends a year sifting through the candidates, on film and on video. The bulk of this work is carried out by Richard Peña, the festival director, and Wendy Keys, the other permanent member of the selection committee. And the remainder is carried out by all five members of the selection committee working as a team — chiefly at the Cannes Film Festival in May, when some of the initial selections are made, and during approximately the first two weeks of August in New York, when all of the final selections are made.

From 1994 to 1997, I served on this committee — one of the most gratifying as well as the most difficult activities I’ve ever had as a film critic. What makes it gratifying is the pleasure of working with a highly capable and congenial group of people, the privilege of being able to see much of the cream of world cinema far in advance of most other critics, the excitement of attending Cannes, and the power and prestige of helping to decide what international films will get the most national attention. What makes it difficult is the job of seeing so many films over relatively short periods of time and then having to reach critical conclusions about them. This becomes especially hard in August, when one has to make decisions about close to a hundred films, most of them features.

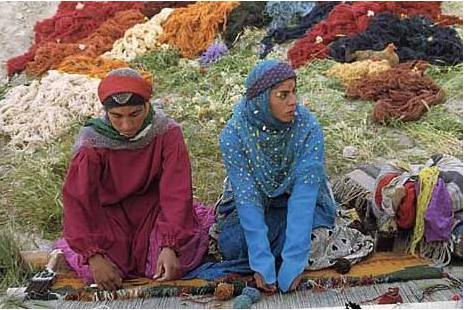

Because of its undeniable influence on American film culture, the power of the festival assumes mythical proportions that often lead to rumors, recriminations, and various controversies. Having followed the festival for almost three decades as an outsider before I became an insider, I can testify personally to the spell exerted by this mythical aura. because it’s never possible for an outsider to know all the various factors that play a part in the deliberations — factors having to do with such matters as when and how preview copies are made available, finding appropriate choices for opening and closing nights (which attract many spectators who don’t attend other programs), the desire for an overall balance between popular and “difficult” films (such as The Ice Storm, Pulp Fiction, and Ed Wood on the one hand, Satantango, The Taste of Cherry, and Von Heute auf Morgen on the other), the subtle and not-so-subtle pressures exerted by some distributors with some foreign films of acquiring subtitled versions — it’s always easy to jump to erroneous conclusions about why certain films are accepted or rejected. As an outsider, I used to complain that too many of the final selections already had U.S. distributors, but what I didn’t realize at the time was that many films found distributors after — and in some cases because — they had been selected by the festival months earlier. And as an insider, to cite another example, I discovered last year that the only way the festival could acquire a particular favorite of mine — The House is Black, a short film made by the great Persian poet Forough Farrokhzad in 1962 — was for me to agree to subtitle it myself, with the help of several others, most of them Iranians (a labor of love that proved to be well worth the effort).

I’ve learned from previous committee members that during the years when the late Richard Roud — who co-founded the festival in 1963 with Amos Vogel — was director, final decisions were reached by voting. Once Richard Peña became director in 1988, a more complex system of arriving at decisions by consensus took hold –a system requiring a great deal of collective effort as well as discussion. This seldom means that all the committee members think and feel the same way about the films in question, but it does mean that a concerted group effort becomes an integral part of the process. This is especially true in August, when seeing seven or more features a day creates a mental strain that can be alleviated only by the confidence that even if one’s attention is temporarily flagging, the chances are good that at that moment one’s colleagues are more alert.

For me the drawbacks of this system is that one’s critical faculties can’t always operate at their best in such marathon conditions. Yet given the thousands of submissions, it’s difficult to think of any practical alternative way of getting the work done. My own experience as a critic tells me that some of the best films I’ve ever seen (e.g., Day of Wrath, Alphaville, Goodbye South, Goodbye) aren’t works whose greatness was fully apparent to me when I first saw them; and conversely, some films that look extraordinary at first viewing, such as Through a Glass Darkly or Gabbeh, seem less impressive when one returns to them days, months, or even years later. This is the gamble one always takes as a critic, and I’m grateful to the New York Film Festival for having allowed me to take these risks when the stakes and the consequences are unusually high — and the conditions of taking them couldn’t be more agreeable.

Postscript [2011]: Just a few of my favorite films that were rejected (or passed over) by the New York Film Festival, for one reason or another: all of Jacques Tati’s last features, all of Edward Yang’s films prior to A Confucian Confusion, all of Pedro Costa’s films prior to Ne Change Rien, Stanley Kwan’s Actress/Centre Stage, and Kira Muratova’s The Asthenic Syndrome.