In memory and appreciation of Sidney Lumet (1924-2011). This appeared in the March 17, 2006 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Ask the Dust *** (A must see)

Directed and written by Robert Towne

With Colin Farrell, Salma Hayek, Idina Menzel, Donald Sutherland, Eileen Atkins, and William Mapother

Find Me Guilty *** (A must see)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Written by Lumet, T.J. Mancini, and Robert J. McCrea

With Vin Diesel, Ron Silver, Peter Dinklage, Linus Roache, Tim Cinnante, Annabella Sciorra, Raul Esparza, and Alex Rocco

John Fante’s slim 1939 novel Ask the Dust, one of four autobiographical novels about his surrogate, Arturo Bandini, has a childlike lyricism that recalls William Saroyan and Jack Kerouac. “I climbed out the window and scaled the incline to the top of Bunker Hill. A night for my nose, a feast for my nose, smelling the stars, smelling the flowers, smelling the desert, and the dust asleep, across the top of Bunker Hill. The city spread out like a Christmas tree, red and green and blue. Hello, old houses, beautiful hamburgers singing in cheap cafes, Bing Crosby singing too.” In this novel Fante celebrates his 20-year-old self from a vantage point of almost a decade later, but unlike Saroyan and Kerouac, he also criticizes that earlier self. He mocks his self-absorption as a struggling writer in the Bunker Hill neighborhood of Los Angeles and ridicules his attempt to cover his own embarrassment about being Italian-American by sneering at the ethnicity of the Mexican-American waitress he falls in love with.

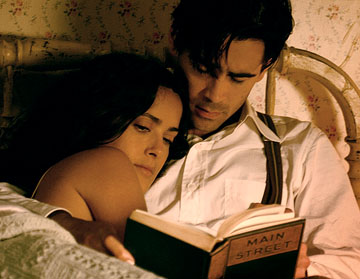

The depth and intensity of Fante’s autocritique are missing from writer-director Robert Towne’s sexy, sensual, romantic, nostalgic adaptation of the novel, a labor of love he’s been trying to realize for years — he discovered the book while researching Chinatown, his most famous script. Towne isn’t blind to Bandini’s self-deception, but since this is a Hollywood romance, he has to spend most of the movie cozying up to the audience, which includes romanticizing Bandini (Colin Farrell) and the waitress, Camilla Lopez (Salma Hayek), as well as downplaying Bandini’s troubled Catholicism and the virginity he loses to a Jewish-American woman he doesn’t love.

Towne makes Lopez much more devoted to Bandini than in the novel, and he erases her psychological instability, which in the book lands her in a mental hospital. He also makes her illiterate, allowing Bandini to teach her how to read, and lets their relationship end with a tear-jerking farewell, giving his story a neat closure the novel lacks.

But to Towne’s credit, he’s a thoughtful and conscientious romantic. He skillfully makes the two main characters a hot, volatile couple, deftly staging their courtship as if it were an erotic grudge match. During this period Fante was supported by H.L. Mencken, who was publishing him in the American Mercury. The novel calls Mencken J.C. Hackmuth, and it’s perfectly reasonable that Towne removes that disguise. (When Mencken briefly wrests the voice-over from Bandini, his words are spoken by Time film critic Richard Schickel.) Towne also re-creates southern California during the Depression with an exactitude that’s all the more impressive given that he shot the movie in South Africa. At this distance he can make both Bunker Hill and the Depression, with all their deprivations, seem alluring, yet he also reminds us how much a nickel once meant to a starving writer.

Like Ask the Dust, Find Me Guilty is a kind of parable derived from a true-life story, in this case one of the longest criminal trials in American history — the 1987-1988 trial of the charismatic if buffoonish New Jersey mobster Giacomo DiNorscio (Vin Diesel), who insisted on acting as his own attorney. Rather than take up the thorny issue of how much of this movie is fiction, I’ll grant it the artistic license it asks for and consider instead the complicity it seeks from us and the lessons it draws from its material. Director and cowriter Sidney Lumet, now 82, stacks the cards so shamelessly in favor of DiNorscio — making the prosecutor (Linus Roache) an insufferable, conniving prig and most of the cops blatant hypocrites — that some viewers may assume the movie carries a procrime message. That’s the conclusion of three of the four early reviews I’ve read, all of which sputter with outrage. I think Lumet is getting at something subtler and far more valuable — tweaking viewers for their weakness for theatricality and asking us what kinds of crime we tolerate and how much we value style over content when deciding. Does our tendency to trust prosecutors derive from their status or their actions? (It’s an especially relevant question today given the flaccid response to the corruption in the Bush administration.) I’m reminded of “Big Jim” Folsom, who served as governor of Alabama twice, in the late 40s and mid-50s, and who presided over blatant graft and corruption. But this grandstanding, alcoholic clown also invited Harlem congressman Adam Clayton Powell to have a drink in the governor’s mansion — a radical gesture for a southern politician at the time — and took progressive stands on women’s and voting rights issues. He seems much more morally ambiguous than a hypocritical racial agitator like George Wallace, and he was arguably an honest crook worthy of not just scorn but admiration. Find Me Guilty suggests, with a clear sense of irony, that the notorious “Jackie Dee” can be read the same way.

Lumet specializes in New York crime stories and courtroom dramas, especially ones that spotlight racial antagonisms and ethnic loyalties. Race and ethnicity are central to his first theatrical feature as a director, 12 Angry Men (1957), and to the three other theatrical films on which he’s taken a writing credit: Prince of the City (1981), Q&A (1990), and Night Falls on Manhattan (1997). I don’t think he’s ever worked with someone quite like action star Vin Diesel, reconfigured for this film and displaying scene-stealing brio as his character tries to persuade the jury he has a tender heart. Does he? I have no idea. But this may be the most Brechtian thing Lumet has ever done — a movie that repeatedly challenges us to think and then to reconsider. No wonder the Hollywood Reporter reviewer was up in arms.