This review was originally written for the long-defunct Canadian film magazine Take One during the same time that I was writing my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), and I’m sure that Pryor’s passionate form of self-examination and autocritique struck a very personal chord for me at the time. To contextualize this review a little further, I had recently written an angry attack on The Deer Hunter for the March issue of the same magazine, not too long after a reviewer in the Soho News had compared it favorably to Tolstoy. –J.R.

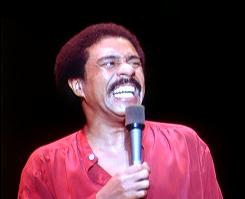

The True Auteur: Richard Pryor Live in Concert

Richard Pryor Live in Concert has nothing in particular to do with the art of cinema; it merely happens to be the densest, wisest, and most generous response to life that I’ve found this year inside a first-run movie theater. A theatrical event recorded by Bill Sargeant, the entrepreneur who similarly packaged Richard Burton’s Broadway production of Hamlet and a celebrated rock concert (The T.A.M.I. Show) fifteen years ago, and more recently filmed James Whitmore’s impersonation of Harry Truman (Give ‘Em Hell, Harry!), it is nothing more nor less than a Pryor stand-up routine given last December 28th at the Terrace Theater in Long Beach, California, lasting about an hour and a quarter. (Patti LaBelle, the singer who preceded Pryor, is omitted from the film but gracefully acknowledged in the credits.)

Now that officially recognized “cinema art” in the U.S. mainly consists of narcissistic, masculine self-pity (Allen, Coppola), xenophobic self-righteousness (Lucas, Schrader), or steamrolling combinations of the two (Midnight Express, The Deer Hunter), it’s perhaps only natural to find an artist like Pryor confidently working the other side of the street. As fine as he’s often been inside the schemes of others – from the broken bum in James B. Harris’s neglected and beautiful Some Call it Loving to the triumphant Daddy Rich in Car Wash – he’s clearly never had a filmic opportunity before this one to let his imagination flourish at full stretch. Working entirely without props, gimmicks, or excuses, he creates a world so intensely realized and richly detailed that it puts most million-dollar blockbusters to shame.

Most of this world, one quickly discovers, is autobiographical, although no less fanciful for being so. In swift succession, Pryor can use his voice and body to impersonate members of his family (from his grandmother to his own children), a horn player in Patti LaBelle’s band, the tires and motor of a car he “killed” with a Magnum (to stop his wife from leaving him in it), numerous animals (including deer, horses, monkeys, and an especially diversified range of Tex Avery-like dogs), John Wayne, a heart attack he recently underwent, a Chinese waiter, a couple of black prizefighters, a host of silly white folks, and even himself, in interaction with all the preceding.

It’s the interaction , in fact, that pushes Pryor’s gifts to the forefront of his art –- the fact that he takes on none of his subjects from a safe, voyeuristic distance, but is constantly implicating himself in whatever he’s dealing with. In the course of sympathetic reviews, both Andrew Sarris and Vincent Canby have objected to what they regard as Pryor’s reverse racism at the beginning of his performance; for me, these gags were only further evidence of Pryor’s boundless empathy. The first time I saw this movie, in a midtown Manhattan theater where the audience was predominantly black, his intuitions about my own insecurities were so acute that I was immediately won over. In point of fact, his impersonations of whites are probably more hilarious and more accurate than any “equivalents” offered in white minstrel shows. It was refreshing to learn, contrary to the incessantly hammered-in xenophobia of so many recent Hollywood packages — from Sorcerer and Star Wars to Midnight Deer Hunter Express — that political ties can still be found, renewed and/or tested among diverse groups inside an auditorium, not broken up and subdivided on the way in by diverse forms of racism and class distinction.

The political issue is basic: Are commercial movies today public forums and community meeting-places, or private sites of narcissistic pleasure, figurative or literal porn images to masturbate to? (A tasty bit of aggressive agit-prop like The China Syndrome falls neatly between these categories.) There’s no question that Pryor belongs to the first camp, because his comedy is a matter of recognition, not confirmation. He lets it all hang out, including how he works. When he falls to the floor in his heart-attack routine, or impersonates his grandmother beating himself as a child — one word per stroke as he sculpts a staccato, crablike chain of blows given and received across the stage, oppressor and victim maniacally encased inside the same voice and body — it seems to be his body thinking, remembering, and speaking as much as his mind. But of course, as Yvonne Rainer reminds us, the mind is a muscle — a lesson demonstrated constantly by Pryor, along with Jacques Tati and Jerry Lewis (in contrast to, say, Lenny Bruce and Woody Allen).

It’s revealing to compare Pryor’s deer hunt with Michael Cimino’s. The latter is so concerned with filling out his pre-set mythical honcho diagram (a bit like painting with numbers) that it would never occur to him to wonder how a deer drinks water when he/she is afraid. Pryor not only wonders; he becomes a frightened deer drinking water — along with himself as a kid and his father watching – in order to find out. Yet who gets praised for “novelistic” depth? A Cimino, who’ll always have to rent his deer from central casting and then ignore it, in order to keep his vision “pure” and calcified; not a Pryor who, wanting to keep his vision alive and impure, will have to look for it in his guts, not send out for it like a cheese Danish. It’s Pryor becoming a whole movie in himself through sheer force and determination who deserves the auteur status. (By contrast, how much of Cimino’s authorship can be attributed to the $13 million that financed it?)

There’s something about the way that Pryor copes with life (at least on a stage) that is positively liberating. What some people have termed obscenity — which has helped to keep the bulk of his work away from the audience who could most appreciate it – is miles away from the violation of taboo pursued by, say, Norman Mailer; Pryor uses language and gesture as a complex means of expression, not a mere act of rebellion. At his most beautiful and poetic, he is actually capable of celebrating the death of his father – at age 57 while making love to an 18-year-old woman – comically exploring the ramifications of all this from her viewpoint as well as from his, and encapsulating the event in a heroic line that seems worthy of a John Donne: “He came and went at the same time.”

—Take One, May 1979, vol. 7, no. 6; slightly revised, July 2009