I believe this was commissioned by the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1993; my thanks to Adrian Martin for reminding me of its existence. — J.R.

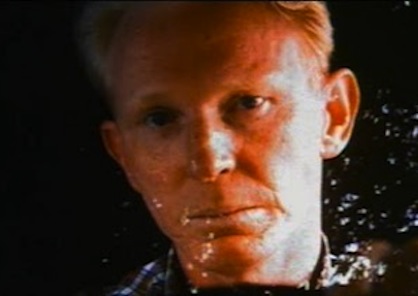

Jon Jost’s three features starring Tom Blair display a surprising amount of consistency and continuity. Part of this undoubtedly stems from the singular power and intelligence of Blair — mainly known as a stage actor and director — who is officially credited for “additional dialogue” only in The Bed You Sleep In, but undoubtedly played a comparable role in earlier films. Another part just as surely comes from the way in which Blair’s particular talents have inspired and inflected some of Jost’s preoccupations. All three films focus on specific forms of all-American male dementia and violence, crumbling economies and communities and family units that come apart through contagious paranoid mistrust. And all three can be further read in part as corrosive, speculative self-portraits that reflect his changing position as a filmmaker. When he made Last Chants for a Slow Dance (Dead End) he was effectively without a fixed address himself and his searing look at the misogyny and wanderlust of Tom, driving around jobless and in flight from domesticity, is in part a dark reading of his own situation at the time. When he started Sure Fire — centered around a desperate real estate speculator named Wes, a patriarchal tyrant with tunnel vision, delusions of grandeur and a compulsive sales pitch — considerations of his own failure to get a commercial release for any of his nine features conceivably exerted some influence. In both films, the hero’s condition is one of solipsistic alienation ultimately leading to blind rage and murder, thrown into acerbic relief by cultural rituals ranging from Johnny Carson to hunting trips. In The Bed You Sleep In, it’s surely significant that Jost’s hero, Ray, a more sympathetic character than either Tom or Wes, owns a lumber mill employing 60 workers, even if it has to import its timber from other countries. If the consequences of this hero’s situation prove to be even bleaker, this time they can’t so confidently and exclusively be tracked back to his own character. While Ray can be charged with ecological rape and winds up being accused by his own daughter of sexual abuse, the film takes pains not to establish whether the second charge is true or false and even the first charge can scarcely account for the tragedy that unfolds. Here the sickness becomes more pervasive, complex and mysterious, and no simple finger-pointing can entirely localize it. Even if the film can be read as Jost’s elegiac farewell to the USA before his anticipated move to Europe, it’s still an essential part of his indictment that he can’t regard the USA and himself as totally separate entities. For all its technical rawness, Last Chants still establishes most of the formal procedures of the trilogy as a whole: extended takes in which characters are periodically eclipsed or overtaken by settings; bitter and visually ambiguous dialogues staged in front of mirrors; disturbing epiphanies when solid presences suddenly become transparent; dreamy narrative suspensions effected through music, landscapes, moving highways and 360-degree pans; stretches of aggressive macho speech spiked by chilling and telling refrains. Persisting through these tropes and others is the beauty and witness of nature, especially vibrant in the new film, offering no escape or respite from the malaise of a disintegrating culture.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum