This review, one of the most incendiary I’ve ever written, appeared in the March 1979 issue of the Canadian monthly Take One (vol. 7, no. 4). It’s probably over the top, but at least it’s sincere; I can’t recall another occasion when any acclaimed movie filled me with such absolute loathing. I can recall thinking, when Cimino subsequently collected his Oscar, that he should have said at the time, “I’d like to thank especially the Vietnamese people, without whose corpses this award wouldn’t have been possible.”

The film is currently screening on Bologna’s Piazza Maggiore, although I’m delighted to report that programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht had the brilliant idea of screening Cinetract 101 just before it. — J.R.

“You beat me, baby,” Francis Ford Coppola reportedly said to Michael Cimino, director of the $13 million The Deer Hunter, in reference to the fact that this new Vietnam atrocity movie has opened several months before Coppola’s Apocalypse Someday. Considering the degree to which slick media and its prize monoliths now seem to rule most of our cultural and ethical discourse, I wonder whether Coppola might have said the same thing to the Reverend Jim Jones if, after the Guyana “suicides,” the latter had been around to receive the compliment. Maybe it’s Jones after all who deserves the Oscars.

Try and imagine a boneless elephant sitting in your lap for three hours while you’re trying to think. It’s flabby beyond belief, convinced not only of its importance but its relevance to Americans (i.e., human beings) everywhere, and even winds up bleating a mournful rendition of “God Bless America” in your ear, hoping that you’ll join in or at least have sympathy for its plight. Waving its snout in your face, it asks you to suspend whatever precious intelligence that you have in exchange for a good cry about what nasty old Vietnam has done to poor beleaguered America. And in order for this to sing through your sinuses, you have to be stirred by its tearjerker premises, which derive from yet another unconsumated macho all-male love story which puts more faith and value in violence than in women.

If only we could send this heavy grey lump off to school, or at least get it a respectable job at the circus. Unfortunately, it comes into our lives and our neighborhood theaters with all the right social connections and credentials — a nod from the new-boy network of Coppola, Milus, Schrader, Scorsese and Spielberg — which means that even some colleagues of mine who dislike the film are capitulating to marketplace pressures and assigning it an aesthetic importance they wouldn’t dream of doling out to a Dreyer or a Visconti.

You think I’m exaggerating? During the same period that The Deer Hunter was being press-shown in New York — before opening for a limited run in New York and Los Angeles in order to qualify for the Oscars it is so nakedly salivating to reap — I happened to hear that all U.S. prints of Dreyer’s Gertrud were being junked. Are we to conclude from this that a dull clinker in the national poet laureate sweepstakes is infinitely more important and meaningful to all of us? And now that the most challenging European films are being virtually banned from and by the media, the expensive American art movie is being given the sweep of the market. (Is it any coincidence that Interiors, Days of Heaven, and The Deer Hunter are all “heroic” movies about cripples?) Thus Pauline Kael is perfectly right in a way when she calls The Deer Hunter an “epic that is scaled to the spaciousness of America itself”. It we read “America” as a code word for our shrinking film consciousness, I’d estimate that that’s currently about two inches wide — at least in the preening mirror that media use to represent our collective face.

A personal confession seems in order. As someone who regards Coppola, Milius & Co. as talented men without a good solid pound of genius between them, I’m not likely to be awed by the high school diploma of one of their greener disciples. From the moment that Cimino’s dull heroes (Robert De Niro, John Savage, Christopher Walken) make their exit from the steel factory in an imaginary Pennsylvania town, and De Niro starts laying on some jock mysticism about those “sun dogs” in the clouds — “old Indian things” that are supposed to portend dire events, apparently in the manner of Tolstoy — we already know that we’re in for amateur night.

And when the director proceeds to lumber us through a Russian Orthodox wedding and a Vietnam send-off party for the heroes modeled on the Godfather bashes, the “richness of novelistic detail” usually adds up to about one simple idea per sagging shot, while the main instruction to actors and extras appears to have been, “Look typical,” perhaps in order to maintain this purity of intention. A folksy festive crowd gets dubbed by an all-male Russian choir, and after most of the beer-spraying chums drive off to the mountains to pursue their Big Wednesday capers, Cimino abruptly shifts to the style of a baby Leni Riefenstahl (or Daniel Schmid) filming a remake of Bambi from the hunters’ viewpoint. The heavenly male chorus resumes as De Niro sights his deer — which he kills in one shot, according to his profound mystic code. (Taking a second shot would be “pussy”.)

Back in the bar, we’re treated to a piano performance of Chopin (art, get it?) by one of the boys, and the camera pans interminably around the the other guys’ thoughtful faces — a stab at monumentality recalling Stalinist movies about Stalin, with Coppola again as the guide. Kael, who considers this movie “a small-minded film with greatness in it” — apparently believing in the greatness of small minds — proposes that if one of the man “had only fallen asleep the scene might have been as great as it wants to be.” Mail-order recipes for greatness seem to be selling like hotcakes this season; it’s too bad that dudes like Dreyer and Visconti aren’t still around around to benefit from this kindly advice.

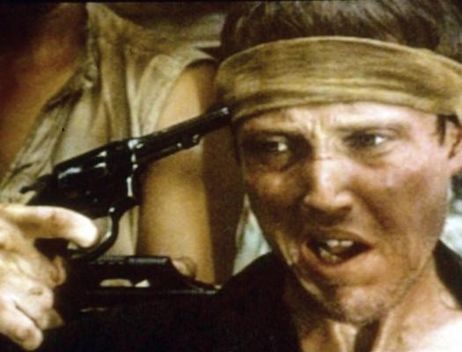

Cut to Vietnam. It seems that what was so awful about this experience for Americans was principally a Russian Roulette game that Cimino himself invented, although the movie credits it to the Vietcong. It consists of taking two prisoners and giving each one in turn a revolver with one bullet and five empty chambers, and slapping each prisoner until he points the gun at his head and fires (giving De Niro a chance to redo his Taxi Driver epiphany). To make things more sporting, cash bets are placed by the Vietcong on whether somebody does or doesn’t splatter his brains on the table. If he does, the Vietcong laughs, like Ming the Merciless. It’s a cute game all right, and Cimino is clearly so enamored with it as a suspense mechanism that he trots it out like a vaudeville routine whenever the action flags, knowing it’ll be a show-stopper each time. (“One of the most frightening, unbearably tense sequences ever filmed,” writes Jack Kroll, “and the most violent excoriation of violence in screen history” — real stuff for the troops.)

After trying this act out in the Vietnam provinces — where all three heroes have magically materialized, to be taken as prisoners and forced to play it — Cimino triumphantly takes it on the road and stages it for greasy foreign civilians in Saigon. Then back on the Pennsylvania mountain, after missing a second deer with the authority of a Zen master, De Niro, in a subsequent fit of pique, tries the game out on his buddy, played by John Cazale — regrettably wasted in his last screen performance. Then, for the grand finale, De Niro flies back to Saigon to retrieve Walken; he has to fork out a few thousand bucks in order to discover that his friend, crazed by his earlier experience of the game, now plays it for a living. (Three shows nightly?)

In an outrageously implausible manuever designed to bring the house down, De Niro is forced to play the game with Walken in order to express his love for him. You think that’s enough for an Oscar? Walken obediently splatters his brains out to give us our money’s worth — and incidentally justify Stephen Saban’s description of The Deer Hunter as “the cinematic equivalent of a Russian novel, a film more Russian than Dr. Zhivago…possibly one of the best films ever made.” Considering that it’s Russian Roulette and that De Niro plays a character named Vronsky, how could it possibly be otherwise?

—Take One, March 1979