From the Chicago Reader (August 13, 1993). — J.R.

RISING SUN

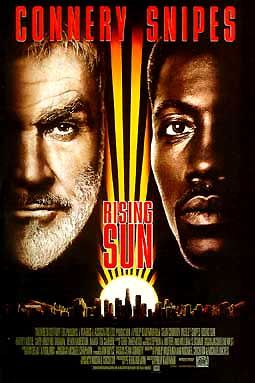

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Kaufman, Michael Crichton, and Michael Backes

With Sean Connery, Wesley Snipes, Harvey Keitel, Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa, Kevin Anderson, Mako, Ray Wise, Stan Egi, Stan Shaw, and Tia Carrere.

Before seeing Rising Sun and then reading the Michael Crichton thriller it’s based on, I happened to read four negative reviews of the movie, and was more than a little taken aback by them. Here are samples of what I found:

“Following the cut-and-dried police procedural structure of the book, cowriter and director Philip Kaufman has soft-pedaled the critique of Japanese behavior stateside, which may reduce justification for protests against the film, but also removes much of the material’s bite.” (Todd McCarthy, Variety)

“Trying to transcend the material, the director loses the novelist’s crude but compelling urgency.” (David Ansen, Newsweek)

“Crichton’s novel was largely powered by his animus against the Japanese business culture, and perversely, you miss his outrage.” (Richard Schickel, Time)

“Crichton, in his novel, was accused (with some justification) of Japan-bashing, but if his vision of Japanese executives as omnipotent control freaks had a racist tinge, it was also sinister fun. . . . Kaufman may have deluded himself into believing that the book’s paranoid vision of Japanese corporate omnivorousness could withstand being “liberalized.’ It can’t: The story now lacks a compelling villain.” (Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly)

I seriously doubt any of these reviewers meant to say that Rising Sun would be a better movie if it were more racist, but that’s the drift of their remarks. McCarthy, one should add, is one of the country’s best critics and writes for a smaller, more specialized audience: the main purpose of a Variety review is to predict how a film will perform commercially. (Once upon a time this was a clear distinction between trade and mainstream reviews, but whether that distinction still holds is moot.) In any case, I suspect McCarthy correctly surmises that this movie won’t be a hit; the plot is too convoluted, the last act too stretched out.

With the collective impression of these reviews still fresh in my mind, I was pleasantly surprised to find the movie pretty good — not as a mystery story (it’s hard to care very much who the murderer is, and I wound up forgetting his identity only hours later), but as a witty, entertaining gloss on the theme of corruption. Kaufman spreads corruption around among all the characters, heroes included, and diverts us with the gurulike pronouncements of the senior cop Connor (Sean Connery at his most elegant) to his junior partner Smith (Wesley Snipes) about the differences between Japanese and American problem solving. Crichton’s specialty — the technology of image manipulation, already given speculative treatments in his own 1973 Westworld and 1981 Looker — gets some amusing play, and if Kaufman can’t do bupkis here with fight scenes or car chases, at least his cinematographer is Michael Chapman, the man who shot Taxi Driver, and the sound designer is Alan Splet, the unacknowledged coauteur of Eraserhead.

Certainly the movie draws on xenophobic impulses, but it never seems guilty of the contempt for Asians expressed in Sixteen Candles, for instance, by the character Long Duck Dong (Gedde Watanabe), and it even goes out of its way to point up the knee-jerk racism of one of the investigators (Harvey Keitel). (Early in the proceedings Keitel barks, “Shit — we’re giving this country away,” and Connery replies, “Nobody forced us to.”) By making one of the two cops, Smith, black instead of white (as he was in the novel), the movie can be said to deflect and complicate the racism rather than eliminate it. A feeble scene in a Los Angeles ghetto that allows Smith — who, being black, naturally knows all his inner-city brothers — to display some temporary advantage over his white colleague doesn’t help matters much.

But in Kaufman’s mind, I suspect, the point of the movie is neither racism nor xenophobia. What it winds up saying is that corporate capitalism ultimately makes unheroic, morally lax patsies out of everyone, and this made me curious to find out whether Crichton’s book could possibly have suggested the same thing.

Well, it does and it doesn’t. Unlike some of my colleagues, I don’t find the novel more biting or compelling or enjoyable than the movie — in fact I found it a chore to get through — but it is substantially angrier and more unpleasant: no one in the book comes across as very likable. Nevertheless the abuse of the Japanese that the Americans routinely dish out is clearly an important part of the running lecture that is the novel’s chief point; the standard-issue police-procedural plot seems contrived only to justify that lecture. Some of it’s pure cant, in book and movie alike: to argue that for the Japanese “business is war” implies that we peace-loving Americans conduct business in some other fashion. And as Reece Pendleton suggests in NewCity — an observation that applies equally well to the book — the movie is permeated by “post-Cold War, conspiracy-minded paranoia, with the shadowy world of powerful Soviet agents now replaced by the equally shadowy world of powerful Japanese businessmen.” Just how much of this “conspiracy” relates to corporate capitalism and how much of it relates to Japanese corporate capitalism is a point the movie, unlike the book, deliberately blurs, which means that viewers with very different biases can find whatever they’re looking for here — an ambiguity that perfectly suits big-time Hollywood filmmaking, whose goal is to please everybody.

Broadly speaking, the book’s message is that Americans are jerks for having let the ground be sold from under their feet, and if that were all Crichton had to say there would surely be less reason for controversy. More problematic is the book’s argument about the Japanese “character,” which receives its climactic expression in Connor’s explanation to Smith about why he left Japan after living there for several years — a scene significantly dropped in the movie. Here is Connor’s bottom line:

“‘Most people who’ve lived in Japan come away with mixed feelings. In many ways, the Japanese are wonderful people. They’re hardworking, intelligent, and humorous. They have real integrity. They are also the most racist people on the planet. That’s why they’re always accusing everybody else of racism. They’re so prejudiced, they assume everybody else must be, too. And living in Japan . . . I just got tired, after a while, of the way things worked. I got tired of seeing women move to the other side of the street when they saw me walking toward them at night. . . . I got tired of the exclusion, the subtle patronizing, the jokes behind my back. . . . ‘

“‘Sounds to me like you don’t really like them.’

“‘No,’ Connor said. “I do. I like them very much. But I’m not Japanese, and they never let me forget it.’ He sighed again. ‘I have many Japanese friends who work in America, and it’s hard for them, too. The differences cut both ways. They feel excluded. People don’t sit next to them, either. But my friends always ask me to remember that they are human beings first, and Japanese second. Unfortunately, in my experience that is not always true.’

“‘You mean, they’re Japanese first.’

“He shrugged. ‘Family is family.'”

For Japanese Americans reading this passage I suspect the argument has a very familiar ring. In fact, with a little less euphemism and filigree, it is precisely the discourse heard in this country half a century ago when, by presidential order, many Japanese American citizens were incarcerated in concentration camps on American soil, and arguments about “essential” Japanese characteristics were needed to rationalize this gross maneuver. In fact, if anyone wanted to turn Connor’s argument around and say that white Americans are whites first, Americans second, and human beings third, no better illustration of this “family is family” creed could be cited than the decision to imprison Japanese Americans in 1942.

But it would be rash to say this about “white Americans” because that would necessarily exclude the few white Americans who opposed this policy at the time. Similarly, Connor’s argument — which implicitly collapses “many Japanese friends who work in America” and Japanese Americans into the same category — ignores the people in both categories who contradict this stereotype. Crichton’s argument about Americans being jerks is comparably one-sided: I, for one, didn’t let the ground be sold from under my feet, and I know plenty of other Americans — including Japanese Americans — who didn’t either. The problem with this kind of lazy thinking about “them,” this shorthand jive that allows us to approve all sorts of atrocities against people not like ourselves, is that it’s too easy to do, and impossible to do fairly when it comes to hard cases. In the final analysis, novels like Crichton’s are too much symptoms of the same kind of stupidity they describe to work very well as diagnosis.

I’m not wholly convinced, either, when William J. Yoshino, the midwest director of the Japanese American Citizens League, protests that in the movie “the Japanese . . . are characterized in an overwhelmingly negative manner” — at least not after I saw Rising Sun a second time. Yoshino has a legitimate point, but he indulges in some imprecise film criticism in order to make it: that word “overwhelmingly” teeters on the brink of Crichton-jive. For one thing, the noblest and most courageous act in the entire movie is performed by a Japanese character named Eddie (Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa) on behalf of Smith. The fact that Eddie is a gangster shouldn’t be overlooked, but it doesn’t tell us much because there’s hardly anyone in the movie who isn’t a gangster of one kind or another. And most of the white male characters in the movie envy rather than dislike Eddie for his racy life-style, so calling him an “overwhelmingly negative” character surely doesn’t say it all.

A more detailed expression of Yoshino’s objection to the movie, recently published in USA Today, comes from Karen K. Narasaki, Washington representative of the Japanese American Citizens League: “Rising Sun has no likable Asian main character. The Japanese men are either inscrutable businessmen intent on taking over the USA by whatever nefarious means necessary or one-dimensional gangsters. They are portrayed as masters of manipulation who engage in perverse sexual practices with white women. In fact, the ‘violation’ of white women seems to be symbolic of the ‘invasion’ of the U.S. economy.

“Slurs such as ‘nip’ and ‘Jap perp’ and sweeping derogatory comments abound unchallenged. Most are uttered by a cop character [Keitel] clearly meant to be an acknowledged racist. But he’s a ‘likable’ bigot, Archie Bunker style, so his comments invite amusement more than criticism.”

Narasaki’s criticisms are harder to refute than Yoshino’s, though they aren’t completely accurate. Her remark about the “violation” of white women is justified to some extent, because the movie gets one of its biggest laughs when the cop played by Keitel spies Eddie eating sushi off the nude body of one white woman and licking saki off the nipple of another; the cop remarks, “Plundering our natural resources.” On the other hand, this same cop later reveals himself to be a more pathetic, odious sellout than any other cop in the movie — neither likable nor amusing. Whether or not this revelation cancels out his earlier wisecrack is arguable, but it certainly doesn’t leave the impression that he’s just another Archie Bunker.

Sketching a context for her remarks, Narasaki points out that “Asian-Americans brace themselves every Dec. 7, the anniversary of Pearl Harbor, for vandalism, threats and abuse. Japan-bashing resulted in the tragic 1982 murder of Vincent Chin by two men who blamed Japan for Detroit auto layoffs and mistook him for a Japanese. And there was the California matron who, during a “Buy American’ campaign, shouted at Japanese-American Girl Scouts who were selling cookies at a suburban mall that she bought only from ‘American’ girls.”

No doubt about it — this is our country, a country where all a president has to do to get a lift in the polls is drop a few bombs on Iraq for any reason at all. Whether these hit the right targets, whether innocent people die, is beside the point — he’ll be praised for showing “them” that “we mean business.” (If we can’t do business, at least we can mean it.)

But blaming movies for this state of affairs is like blaming barometers for the weather. It also admits a certain defeat at the outset — targeting fictional representations of racism rather than more lethal and actual manifestations seems too easy. And asking for “positive” portrayals instead of “negative” ones buys into a comparable form of defeat: why be so accepting of generalizations in the first place? Striving for positive generalizations is an understandable recourse given the prejudice and discrimination that most minorities in this country face and the callous demographic calculations that govern most Hollywood movies, but it generally plays havoc with how we see these films. Nor does violence necessarily have anything to do with a movie’s style or content: screenings of New Jack City occasioned violence and screenings of Do the Right Thing didn’t. Given the frustrations and bad vibes in our culture, all sorts of things might spark violence; but if we’re intent on blaming movies, we might just as well cite the documented case of the serial killer who said he was inspired to kill women by the “golden calf” sequence in Cecil B. De Mille’s remake of The Ten Commandments.

Personally, I find Crichton’s novel offensive for its xenophobia and Kaufman’s movie somewhat less so; but neither one is a patch on Sixteen Candles — a movie that went unprotested — when it comes to Asian bashing. And even that movie is less responsible for racism in this culture than the ignorance and desire for generalizations that generated it and other films of its ilk. Disney cartoon features, which get practically everybody’s stamp of approval, strike me as far more dangerous than Crichton’s cartoons for grown-ups — not only because they establish stereotypes for very young viewers but because most people consider them harmless and ideology-proof. Yet if you want to understand some of the attitudes that underlie this country’s treatment of Iraqis, Aladdin isn’t an unreasonable place to go looking for clues.

Kaufman’s movie can be seen as a statement about corporate capitalism, but it’s also a barometer of what many people in this country feel not only about Japanese business but about women, and some of those feelings aren’t very pleasant. Consider the complete lack of concern for, even interest in, the female murder victim who sets the plot in motion in both book and movie. Then there’s the more subtle but no less pernicious way the putative heroine (Tia Carrere), half Japanese and half black, functions as a human beanbag or poker chip for the two heroes — with the movie’s full approval and to the recurring strains of a Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn tune (“The Single Petal of a Rose”) clearly meant to romanticize this grubby transaction.

It could indeed be argued that Kaufman’s attempts to upgrade soiled merchandise (not only his source but the racist portions of his audience) yield only mixed results. I also recognize that it’s a lot easier to enjoy his movie if, like me, you’re not Japanese or Japanese American, and easier still if you’re not worried that the movie, like Crichton’s book, doesn’t distinguish between the two. But given the culture we all live in — a culture that includes a lot more than movies — it’s hard to see how the film could be otherwise. When push comes to shove, generalizations prevail, and one way or another, everyone climbs on board.