Written for Filmkrant‘s “Slow Criticism”, February 2010 (no. 318). — J.R.

There’s a personal reason why Ne Change Rien comes together for me in a way that few music documentaries do. Eight years ago, I was approached by Rick Schmidlin, the producer of the 1998 re-edit of Touch of Evil (on which I’d served as consultant), about writing or directing — in any case, helping to conceptualize — a documentary about jazz pianist McCoy Tyner. This led to a lengthy conversation with Tyner in Chicago and then a three-page treatment that I prepared with cinematographer John Bailey via phone and email, which concluded, “Any film that’s about listening, as this one will be, will also be about looking — predicated on the philosophy that the way one looks at musicians already helps to determine the way one listens to them.”

For me one of the ruling ideas was that few jazz films, apart from a handful of the very best, focused enough on the spectacle of jazz musicians listening to one another. And I saw (and heard) the whole thing as a two-way process — the way one listens should dictate the way one looks, as well as vice versa. Perhaps the most remarkable examples of this happening on film are footage of Charlie Parker reacting delightedly to Coleman Hawkins and Buddy Rich playing solos in Gjon Mili’s never-completed 1950 film Improvisation and Billie Holiday responding to Lester Young’s desolate yet intensely compacted eight bars on “Fine and Mellow” in the 1957 CBS special The Sound of Jazz — her way of looking, listening, tilting and moving her head back and forth with what appears to be equal amounts of pleasure and grief, both ecstatic, the two folded together into some tragic form of boundless love. In fact, filming Holiday in The Sound of Jazz is one of the few models cited by Pedro Costa, along with Godard filming The Rolling Stones in One Plus One (1968).

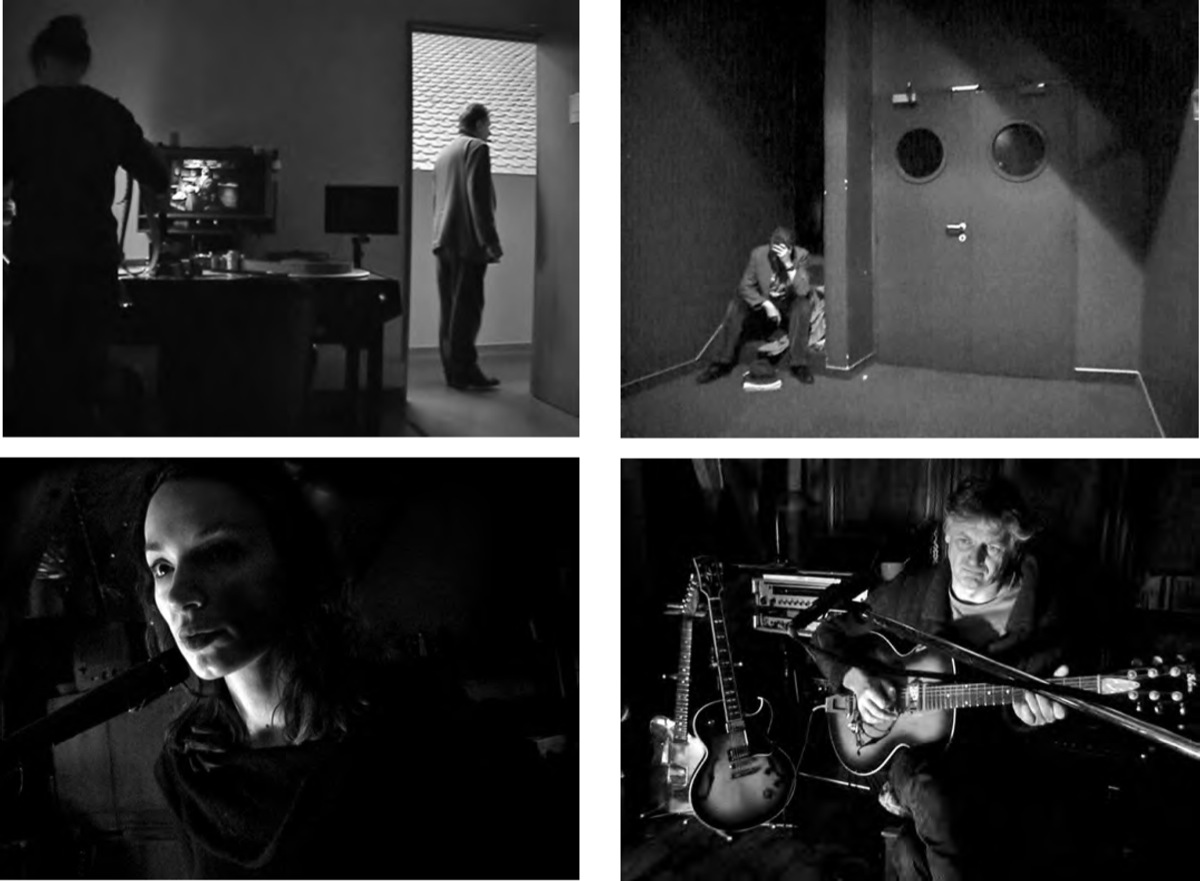

None of this is meant to imply that Ne Change Rien can be reduced to such a simple formula of musicians responding to musicians, even if this principle does assume an important part of its texture. More generally, the film’s “ideas” can’t be limited to either those of Jeanne Balibar and her accompanists and accomplices or those of Costa and his own helpers because they nearly always comprise an interweaving of them all. And this being a Costa film, who starts what is a perpetual mystery — and not one in which our own responses necessarily correspond to those of either the performers or the filmmakers, although modulations and transmutations of various kinds between various players and spectators (including us) are clearly part of the game. It’s the same radical process suggested by Tati’s Parade, according to which one can’t determine when anything starts and when anything stops. Perhaps the most significant difference is that Costa’s play with darkness and the nonvisible adds our imaginative investments to all these fluctuations. (Interestingly enough, he settled on black and white only after accidentally discovering neck veins on Balibar that didn’t register in color.)

Something comparable happens in Where Lies Your Hidden Smile? (2001), Costa’s most accessible film, which shows Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet editing Sicilia! in another dark studio space. Aptly described as a romantic comedy, it’s the only Costa feature that isn’t dark in spirit. And it’s a telling sign of Costa’s radicalism that he can approach the work of artists as radically dissimilar as Balibar and Straub-Huillet in comparable ways.

Blood (1989) already announced the essence of his cinema by declaring every shot an event, regardless of whether or not we can understand it in relation to some master narrative, and Casa de Lava a year later upped the ante, adding color and Cape Verde but also composing some of the most thrilling landscape shots in contemporary cinema, meanwhile critiquing Costa’s own role in composing them. (This prompted me to ask Costa — in Lisbon, November 2008 — why he hadn’t made any more landscape films. “It’s too easy,” he said — which might serve as a working motto for his entire oeuvre.) Bones discovered some friends and relatives of characters in Casa de Lava in Lisbon’s Fontaínhas slum, and the next four films, not counting Where Lies Your Hidden Smile?, remained there, implacably and patiently — not so much waiting for things to happen as witnessing either the survival or the decimation of his friends, their various evolutions, and, eventually, their expulsion from their (and Costa’s) elected turfs.

The fairy-tale poetics of disturbed innocence and threatened violence in Blood evoke Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter — milky whites, inky blacks, and delicate balances of light and shadow already forecasting the graded intensities of Ne Change Rien while recalling certain shades of Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat. Casa de Lava (1990) is plainly an eccentric remake of Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie, and Costa has also described Tarafal as a remake of the same director’s Night of the Demon. Thom Andersen aptly calls Colossal Youth (2006) a remake of Ford’s theatrically lit Sergeant Rutledge (1960), with the traumatized Cape Verdean patriarch Ventura standing in for Woody Strode. Costa’s frequently dazzling color palettes derive in part, he says, from having watched Ford’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) “very, very stoned,” and he has even compared Ne Change Rien to a Nick Ray B-film about “three guys lost in a forest and [finding] some shack,” where there’s a fire, some coffee, and a guitar.

But I have to be frank. Not only does most of Balibar’s music have little to say to me, unlike the music of Hawkins, Parker, Holiday, Young, and Tyner; on my second trip through Ne Change Rien, I found myself actively recoiling from it. (The major exception is a hypnotic stretch, mostly wordless, of a droning vamp that begins 22 minutes into the film and proceeds in a lovely Coltrane-like trance for 14 minutes; if there’s even a trace of this on Paramour, the arty, self-conscious CD that emerged from all this work, I managed to miss it.) How much this disaffection comes from electric guitars or diva stances is probably secondary. My first trip through the film didn’t pose much of this problem, because I thought and felt I was attending to Costa’s ideas, only some of which might have been tributaries of ideas from Balibar, Rodolphe Burger, Arnaud Dieterlen, and a few others, i.e., sound engineer, voice teacher, pianist.

In short, what comes together for me as a film often comes apart as music, and maybe this is as it should be. The film begins with Balibar in the darkest of speckled profiles, singing “You’re torturing me” (uncredited lyrics by Kenneth Anger) at some unidentified club date, and I knew exactly what she meant and felt — or rather, what she was professing to feel, because I can rarely figure out in her songs what statements belong between or outside quotation marks. Or whether they even qualify as statements as opposed to questions, or as enactments as opposed to acts. All I knew was that they were torturing me.

Questions from Costa in the form of shots, no matter how challenging, are still easier for me to entertain than events performed by Balibar in the form of notes and gestures, rehearsed or remembered or both. In the film, where it’s no simple matter to distinguish the dancer from the dance, or the dance from the filmmaker filming the dance, I’m no longer recoiling — just weaving in and out, along with the filmmaker and the musicians, in and out of abstraction, in and out of referentiality, and, even by design, in and out of the music.

But insofar as filmmaking itself is a kind of music, I’m reminded of a 1928 statement by F.W. Murnau — which becomes all the more resonant when one acknowledges that fiction and documentary in both Murnau and Costa are merely two sides of the same coin:

“They say that I have a passion for ‘camera angles’…To me the camera represents the eye of a person, through whose mind one is watching the events on the screen. It must follow characters at times into difficult places, as it crashed through the reeds and pools in Sunrise at the heels of the Boy, rushing to keep his tryst with the Woman of the City. It must whirl and peep and move from place to place as swiftly as thought itself, when it is necessary to exaggerate for the audience the idea or emotion that is uppermost in the mind of the character. I think the films of the future will use more and more of these ‘camera angles,’ or as I prefer to call them these ‘dramatic angles’. They help to photograph thought.”

The fact is, even while clarifying the movement of thought, Murnau has to obfuscate whether the thought belongs to himself, his character, or his audience, choosing to collapse all three within the same privileged zone of voluptuous transport. So when Costa combines the flickering flames of a furnace in a dark recording studio with disconnected phrases of Balibar and Burger noodling, how much this music is being rehearsed or performed or explored or questioned is secondary to the dance of the flames and notes and faces that accompanies this process, which we’re asked to join even before we can think of observing it. Most of the time, it’s the personal transactions and the fantasies we all spin around them more than the actual notes that hold the screen, so it’s small wonder that when we see Balibar and her pals performing “Johnny Guitar” in a club just afterwards, it’s the romance of the idea and the atmosphere as much as the song itself that carries us along: shack, guitar, fire, and coffee finally giving way to Nick Ray mythology, complete with grandiloquent hand gestures. And dark, humanized space, which we recognize from the Fontaínhas films, more than the groping, stammering sounds inside it.