From the Chicago Reader (July 7, 1995). — J.R.

Hyenas

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Djibril Diop Mambety, adapted from Friedrich Durrenmatt’s The Visit

With Mansour Diouf, Ami Diakhate, Mahouredia Gueye, Issa Ramagelissa Samb, Kaoru Egushi, and Mambety.

“The plot by now must be well known; a flamboyant, much-married millionairess returns to the Middle-European town where she was born and offers the inhabitants a free gift of a billion marks if they will consent to murder the man who, many years ago, seduced and jilted her….Eventually, and chillingly, her chosen victim is slaughtered, but I quarrel with those who see the play merely as a satire on greed. It is really a satire on bourgeois democracy. The citizens…vote to decide whether the hero shall live or die, and he agrees to abide by their decision. Swayed by the dangled promise of prosperity, they pronounce him guilty. The verdict is at once monstrously unjust and entirely democratic. When the curtain falls, the question that Herr Dürrenmatt intends to leave in our minds is this: at what point does economic necessity turn democracy into a hoax?”

These words of wisdom from Kenneth Tynan, written in 1960 about Friedrich Durrenmatt’s 1956 play The Visit, are well worth recalling when you make your way to the Film Center this week or next to see Djibril Diop Mambety’s wonderful Senegalese feature Hyenas (1992) at the Black Harvest International Film and Video Festival. The amazing thing about this African adaptation of a famous Swiss tragicomedy is how close it remains to the spirit of its source, as well as what Tynan says about it, despite the fact that it’s also African to the core. When I first saw Hyenas at the Locarno film festival three summers ago I assumed it was at most a loose reworking of the Durrenmatt play, despite Mambety’s insistence to the contrary. But then my knowledge of The Visit came from the arty mess Bernhard Wicki made of it with Ingrid Bergman and Anthony Quinn in 1964; when I finally got around to reading the play it was obvious that Mambety had thoroughly respected his source material. The Visit is one great play; whether this is one great movie as well is something I’m still trying to figure out. But it’s certainly a serious adapatation, and you shouldn’t miss it.

Mambety has transplanted the story from eastern Europe in the 50s to Senegal in the 90s, eliminated the recent husbands of the millionairess, and added a good many consumer appliances — washing machines, TV sets, electric fans, air conditioners — as well as several African animals. He’s cleverly made it both a musical (there are loads of songs) and a western (sweeping landscapes) — neither of which sounds appropriate to the play. I think he gets away with all of this precisely because he’s respected Durrenmatt’s intentions as well as many of his lines: “I have presented a world, not pointed a moral (as I have been accused of doing),” the playwright argues in his postscript, adding that his millionairess “doesn’t represent Justice or the Marshall Plan or even the Apocalypse, she’s purely and simply what she is, namely, the richest woman in the world and, thanks to her finances, in a position to act as the Greek tragic heroines acted, absolutely, terribly, something like Medea….The old lady is a wicked creature, and for precisely that reason mustn’t be played wicked, she has to be rendered as human as possible, not with anger but with sorrow and humor, for nothing could harm this comedy with a tragic end more than heavy seriousness” — which, if memory serves, is precisely what Wicki gave it. Mambety knows better.

It’s also worth pointing out that Durrenmatt’s fanciful stage business — onstage set changes, actors playing trees, birds, and animals — has been sensibly jettisoned, and that what Mambety has added concerning Africa, though it may transcend simpleminded morality or allegory, has things to say about colonial and postcolonial consumerism that Durrenmatt only hinted at. Still, some of Dürrenmatt’s original hints are pretty potent. For those who assume that a “new world order” is a concept dreamed up by George Bush, the following speech by the millionairess to the villagers in the play — some of it retained in this movie — is instructive: “Feeling for humanity, gentlemen, is cut for the purse of an ordinary millionaire; with financial resources like mine you can afford a new world order. The world turned me into a whore. I shall turn the world into a brothel.” (It seems significant that she has artificial limbs, the result of an auto accident; the implication — moral as well as dramatic — is that she’s been manufactured by the world we live in.)

***

Missing from Tynan’s plot summary are the insidious steps over several weeks by which the villagers con themselves into murdering the hero, who runs a general store. In the movie this store is also the local bar and cafe. (From here on, I’ll call the characters by their names in Mambety’s film: the hero, played by Mansour Diouf, is Draman Drameh; his vindictive ex-lover, played by Ami Diakhate, is Linguere Ramatou.)

At first the villagers, despite their desperate poverty, are indignant at Ramatou’s offer and proudly reject her proposal, proclaiming their solidarity with Drameh. “I’ll wait,” she replies sanguinely and departs with her retinue, a party including a female Japanese bodyguard and a valet, a former judge who once ruled against Ramatou when she lodged a paternity suit against Drameh.

As one of the male villagers who’s in Drameh’s store the next day puts it, “That woman Ramatou is crazy. She thinks we’re Americans who’d kill each other for nothing.” Yet spurred by the mere thought of wealth, they immediately start to buy luxuries from Drameh on credit, and after they get a taste for them the process of rationalizing their gradual change of heart begins. The police chief refuses to arrest Ramatou when Drameh brings charges against her; then the mayor withdraws his support of Drameh as his successor, saying that even if Ramatou’s cash offer is odious, Drameh’s treatment of her 30 years earlier, including his calling two false witnesses at the paternity trial, raises questions about his qualifications to be mayor.

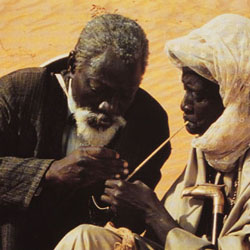

Arguably, Mambety’s subject as well as Durrenmatt’s becomes the transformation of social will as a function of imagination rather than simple greed. Pivotal in this process is a carnival sequence devoted to the spell exerted by electric appliances on the villagers — a scene entirely of Mambety’s invention — during which one housewife says, “The fridge will keep my husband cool, and the TV will keep my children at home. That’s what I want.” According to Mambety, the process by which a simple, understandable desire for such products becomes inextricably intertwined with a rationalization for murdering a favorite local citizen is not simply a target for self-righteous satire but something much more complex and profound, more realistic and terrible. Moreover, Mambety doesn’t just point to the evil but fully implicates himself in it — as is shown by the fact that he himself plays the former judge now working as a servant to the rich. Maybe he’s saying something about making movies as well.

***

Hyenas is Mambety’s second full-length feature; his first, the remarkable Touki Bouki, was made almost 20 years earlier. For the past two decades he’s been working mainly as a stage and film actor in Senegal and Italy, and his wonderful way of handling actors throughout Hyenas undoubtedly stems in part from his own magisterial sense of presence.

Touki Bouki (1973) has been described in some quarters as the first African avant-garde film; considering how poorly it did commercially — in part, one suspects, because of its stylistic and formal subversiveness — it isn’t too surprising that Hyenas is much more conventionally conceived. But according to Nwachukwu Frank Ukadike’s recently published Black African Cinema, the “avant-garde” label we place on Touki Bouki may say more about us than it does about Mambety: “While non-African critics have read the film as an avant-garde manipulation of reality, an Africanist analysis would attempt a reconfigurative reading that synthesizes the narrative components and reads the images as representing an indictment of contemporary African life-styles and sociopolitical situations in disarray.” When people describe films as “avant-garde” or “deconstructive” what they usually mean is that they’re abstract, turned away from the sociopolitical implications of a story, but Mambety may be working in the opposite direction in both of his features.

One thing that links these features is a reference to hyenas in their titles; the English title of Touki Bouki is The Hyena’s Journey. If we’re wondering who all these hyenas are, a text furnished by Mambety for the press materials of Hyenas is suggestive:

“The hyena is an animal of Africa. Singulary wild. It practically almost never kills. First cousin to the vulture. It knows how to sniff out illness in others. And then is capable of following, for a whole season, a sick lion. From a distance. Across the Sahel. To feast one evening on its corpse. Peacefully.” That describes all the villagers, which means all of us. And I suspect it has something to do with TVs, air conditioners, washing machines, and the bulldozer that appears in the final sequence — everything we’re uncritically and carnivorously fond of calling progress.