From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 505). A tinted restoration of this film was presented at Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato with a beautiful, large-orchestra score composed and conducted by Timothy Brock a few years back, and I must say that this very impressive presentation substantially transformed my original skepticism, fully demonstrating how much difference a serious archival restoration can make. And Flicker Alley has brought out this version on a lovely Blu-Ray, which I can heartily recommend. — J.R.

Feu Mathias Pascal

(The Late Mathias Pascal)

France, 1925

Director: Marcel L’Herbier

Miragno, Italy. Acting on behalf of herself, her son Mathias and her sister-in-law Scolastique, Maria Pascal authorises agent Batta Maldagna to sell her property; worried about her debts, he sells it at one-sixth its value. Mathias’ shy friend Pomino, secretly in Iove with Romilde Pescatore, asks Mathias to propose to her on his behalf at a village fête. Discovering that she is-in love with himself, Mathias marries her instead, but soon finds his life made miserable by his shrewish mother-in-law, who holds sway over Romilde. He goes to work at the chaotic municipal library, where his time is largely spent contriving to catch rats. After the nearly simultaneous deaths of his mother and infant daughter, he flees to Monte Carlo, where, by following the advice of a gambler who tells him to bet on 12, he unexpectedly wins a fortune. On the train back to Miragno, he reads an account of his own suicide in a newspaper and decides to take advantage of this mistake by assuming a new identity.

Switching trains, he proceeds to Rome and begins to check into a luxury hotel until he realises that he cannot refister without giving himself away. Renting a room from Anselmo-Paleari, and calling himself Mr. Adrien after hearing the name of Anselmo’s daughter Adrienne, he falls in love with her and is horrified to discover that she’s engaged to tourist guide Térence Papiano — a match encouraged by alcoholic medium and fellow boarder Saldia Caporale, who greatly influences Anselmo. During a seance, Térence’s epileptic brother Scipion steals 50,000 lire from Mathias’ room. Unable to press charges because of his secret identity, Mathias secures Adrienne’s promise not to marry Térence and returns to Miragno, frightening and intimidating Romilde -– now married to Pomino, and with a child by him — along with her mother and Maldagna, now running for re-election as mayor. After putting his affairs in order and visiting his ‘grave’, he returns to Rome and marries Adrienne.

It is one of the unfortunate consequences of historical short-sightedness that the only work of Marcel L’Herbier now available in this country is the dated Feu Mathias Pascal, while the extraordinary L’Argent — made only three years later, but not really ‘discovered’ until 1968, by Noël Burch — should remain inaccessible. Checking the standard film histories, one finds that at least one reason for the earlier film’s reputation still remains at least partially viable: as a vehicle for Ivan Mosjoukine, it amply serves — through its arsenal of shifting stylistic strategies — as a showcase for his versatile talents. And from a more academic standpoint, the movie affords one the opportunity to see the first film performances by Michel Simon (made up so heavily that he almost resembles Catherine Hessling) and Pierre Batcheff (the principal character in Un Chien Andalou), and the first work in Paris by Cavalcanti and Lazare Meerson. Less enduring, alas, are most of the qualities that originally gave the film some status as a literary adaptation. It was the first of Pirandello’s works to be brought to the screen, and L’Herbier still speaks with pride about the approving letter he received from the author.) It is, to be sure, unusually faithful to the novel’s plot: although Mathias Pascal’s first-person narration is dropped along with several characters (such as his childhood tutor) and incidents (such as his eye operation in Rome), a running time of over three hours allows L’Herbier to retain a considerable amount of the original’s detail, which location shooting in San Gimignano, Rome and Monte Carlo (along with studio work in France) further enhances. The problem is that Il Fu Mattia Pascal, far from being a ‘classic’ novel, isn’t even a very good one; a sprawling, meandering account of a glib aristocrat demonstrating his apparent superiority to everyone around him, it takes over three hundred pages to embellish an anecdote that Hawthorne, in a story like Wakefield, could have managed in ten — and it similarly takes the film a full ninety minutes to arrive at the hero’s sudden decision to assume a new identity.

Much of the film’s exposition, moreover, is handled by titles which the visuals mainly illustrate. But it should be acknowledged, in all fairness,_ that many individual shots and sequences are brought off with a distinctive visual flair: the first encounter of Romilde and Mathias, passing on the street, uses natural lighting to split both characters and screen into a striking division of white and black, while the comparably expressionist village fête makes an affecting use of smoke and silhouettes; and a graceful set of dissolves takes us from this event straight into Mathias’ marriage, for once without a title. Elsewhere, irises, superimpositions, slow-motion, blurred focus and tilted angles are all put to expressive narrative use; and if in each case these devices seem purely ‘localised’ rather than the product of any consistent strategy, they resemble in this respect Mosjoukine’s performance, which often appears to aim more at isolated effects than at a harmonious creation.

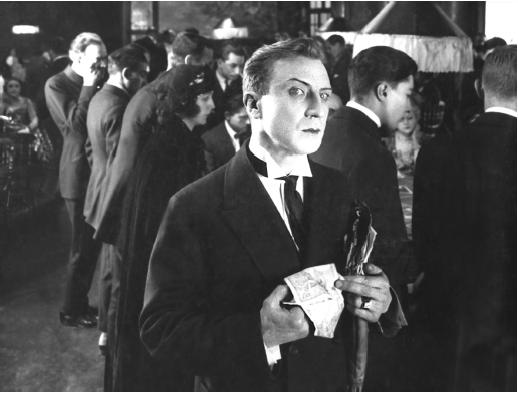

Oscillating between the varying stances of a romantic lead, a sorrowful young Werther, a hapless innocent and a cadaverous Nosferatu — and thereby suggesting that he has more identities at his disposal than the character he is playing — Mosjoukine is most inspired in scenes which seem to reflect a Keaton influence, in the use of gadgets as well as in his own demeanor: attaching a string to his daughter’s cradle so that he can rock her by dancing a little jig while knotting his tie or, in the film’s most appealing scene, enlisting the reluctant aid of two kittens in ridding the ramshackle library where he works of some bibliophile rodents that are nearly as big as the cats. JONATHAN ROSENBAUM