From the Chicago Reader (October 25, 1991). — J.R.

LITTLE MAN TATE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jodie Foster

Written by Scott Frank

With Adam Hann-Byrd, Jodie Foster, Dianne Wiest, Harry Connick Jr., David Pierce, Debi Mazar, and P.J. Ochlan.

Part of what’s refreshing about Jodie Foster’s first feature as a director is its quirky style and vision; even the picture’s limitations have a certain offbeat integrity. In 90 percent of the movies we see the flaws are the same old flaws endlessly recycled (inherited like family curses, passed along like viruses): sentimentality, cliched characters and behavior, and stock attitudes, camera placements, and audience manipulations. Relatively free of these familiar blemishes, Little Man Tate winds up with a few of its own — “missing pieces” might be more accurate — but most of these problems seem to have been arrived at honestly rather than automatically imported from other movies.

The title hero is a boy genius named Fred (Adam Hann-Byrd) who occasionally narrates his own story, which transpires mainly between his seventh and eighth birthdays. He’s gifted in so many ways that, at least on the schematic level of Scott Frank’s script, he often seems like several boy geniuses jammed together: a self-taught reader by age one, he also quickly reveals himself to be a talented visual artist, a remarkable classical pianist, an original and accomplished poet, and a mathematical wizard who breezes through a college course in quantum physics when he’s seven. Since the movie doesn’t seem to be science fiction, we can only regard these oversize credentials as some massive instance of Hollywood wish fulfillment. However, virtually every Hollywood movie involves wish fulfillment on at least as massive a scale; Little Man Tate differs mainly by shifting the focus of its fantasy. Instead of the perfect romance, perfect summer, perfect orgy of destruction, perfect home, or perfect murder, this picture simply postulates a perfect little boy.

Not a very happy one, however: by the age of seven Fred Tate has developed ulcers and suffers keenly as a social outcast. He has no father but is blessed with a loving working-class mother named Dede (Foster). Eventually he comes to the attention of a child psychologist, Jane (Dianne Wiest), a former child genius herself who runs an institute for gifted kids and wants to enlist Fred. It soon emerges that if Dede is all heart, Jane is all head, and most of the remainder of the movie is devoted to the emotional negotiations that must take place between these two women and within Fred before he can embark on a happy childhood.

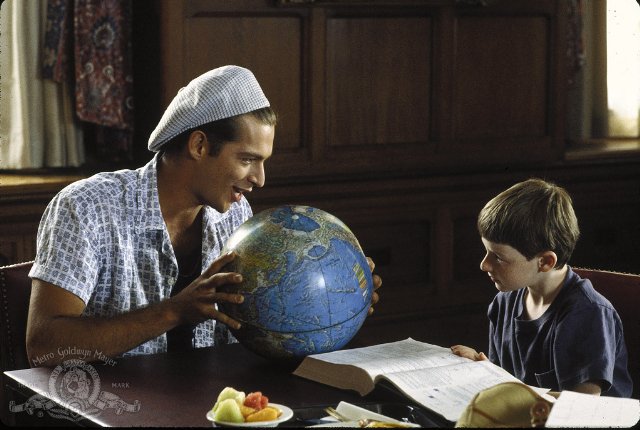

It’s a highly schematic setup, illustrated and amplified by everything from production design (Dede’s muddy-colored slum apartment versus Jane’s glacial institute and home) to jokes about food and other domestic arrangements. In a way, Foster seems to be using this conceptual master plan as a kind of safety net: every camera setup seems carefully planned, every move in the narrative as Fred bounces back and forth between maternal figures seems plotted on a graph. But establishing this overdeveloped structure seems to free Foster to break from it. If the script unduly schematizes Fred and Dede, the performances of Hann-Byrd and Foster are so agreeably loose and malleable that these characters spring to life, confounding their stereotypical roles. Playing much of the story for comedy, Foster has commissioned a wonderfully airy jazz score from Mark Isham (a film composer known mainly for his new-age music for Alan Rudolph) that gives the whole movie a footloose, bouncy feeling. It’s as if Foster were daring her characters and even her own mise en scene to break free from her storyboards, and the strategy often works. A relaxed and amiable performance by Harry Connick Jr. as Eddie — a college jock who briefly befriends Fred and who plays some Erroll Garner-influenced jazz piano — perfectly illustrates this casual side of the film.

Significantly, Eddie is the only adult male who plays an important emotional role in Fred’s life–and his role is extremely short-lived, consisting of one afternoon of hanging out together. But the film never posits the absence of a father figure as a serious factor in Fred’s upbringing. Indeed, the only patriarchal figure who comes to mind is a ludicrously myopic and insensitive stuffed shirt: an upper-crust “cultural” TV talk-show host named Winston F. Buckner (George Plimpton) who registers as a parody of William F. Buckley. Fred at one point in his narration solemnly conveys his mother’s apparently frivolous claim that he was the product of immaculate conception; and at no point does Dede express or even hint at any intention to marry (or remarry). The implication that Fred can get along fine without a father or a father surrogate is the most radical idea this movie has to offer — but it’s an idea that’s implicit rather than expounded.

Reputedly Foster herself was a precocious child, raised mainly by two women, which suggests a personal if not strictly autobiographical relationship to the material. In the film’s fictional world, Fred’s happiness depends on finding a balance between the nurturing benefits of two adult women and a feeling of kinship with other male children. Within this constellation, Fred’s fleeting bond with Eddie carries some weight; but when it ends we’re not made to feel that the loss is irreparable. We’re more likely to regard it afterward as part of another thematic constellation in the film — Fred’s yearning for a normal life and friends, which draws him to unexceptional people as well as to other gifted children. (In this respect Fred is quite different from Damon [P.J. Ochlan], an older child genius in Jane’s care: this tortured smart-aleck in a cape, whom Foster seems to understand quite acutely, clearly suffers from the lack of a mother like Dede.)

Fred’s yearning for normality leads to one of the film’s dramatic climaxes–the child’s disastrous appearance on Winston F. Buckner’s TV show with Jane and several other precocious kids; Dede, stranded some distance away in a Florida motel, watches him helplessly on TV. Scenes demonstrating Jane’s insensitivity to Fred’s need for affection have elaborately prepared us for this crisis, which culminates in Fred’s reciting on TV a bland “poem” about clipper ships. In fact it isn’t a poem but a repetition of a class theme once delivered by one of the most normal boys in Fred’s grammar-school class. Like Fred’s lying that he wants to be a fireman when he grows up, reciting this theme as his own poem points to a desperate need to be accepted as ordinary, recalling the pathos of the superchildren in such science-fiction stories as Wilmar H. Shiras’s “In Hiding,” Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John, and Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human.

Unfortunately, the script dramatizes this scene still further by intercutting it with another drama going on at the Florida motel. While she’s watching Fred on TV, Dede is also keeping an eye on her friend’s kids in the motel pool. But she’s so distracted by Fred’s distress that she doesn’t notice one of the kids is nearly drowning; she sees it just in time to pull him out of the pool and revive him with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. The meaning of this scene is clear enough — Fred is “drowning” before her eyes — but the fancy montage effect makes it seem contrived. And the consequence is that we’re likely to be distracted ourselves from the full meaning of Fred’s behavior.

I should say that lapses of this kind are relatively infrequent in Little Man Tate. The only other that comes to mind, apart from an instance or two of weak continuity, is a lavishly overdetermined and somewhat unconvincing happy ending, which might have worked better if we’d been given one final extended scene between Dede and Jane.

Foster’s sense of camera placement is both original and highly functional throughout, from the opening shot — an overhead angle of Dede with her newborn baby that slowly descends in a spiral motion — to the climactic moment in the movie’s penultimate scene when Jane’s decision not to intervene between Dede and Fred is dramatized by her out-of-focus silhouette appearing in and then disappearing from a lit doorway in medium long shot, without the nudging emphasis of a close-up. When it serves her story, Foster doesn’t hesitate to have the camera retreat from a window that frames Dede dancing with Fred in their flat, or even to position it inside an oven to observe Jane triumphantly pulling out a meat loaf. She has the imagination to vividly enter Fred’s mind for two brief but lively fantasies (involving numbers and billiard balls) and two eerily succinct nightmares, and the control in another sequence to purposefully oscillate between film and video. I can only hope she gets the chance to direct more movies, because this is a remarkable first effort.