A column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, printed in their March 2023 issue (#170).. — J,R.

It’s because I don’t understand this woman, because I didn’t understand her at the trial, and I still don’t understand her now….That’s what I offer to the viewer—to ask him or herself questions.

Alice Diop

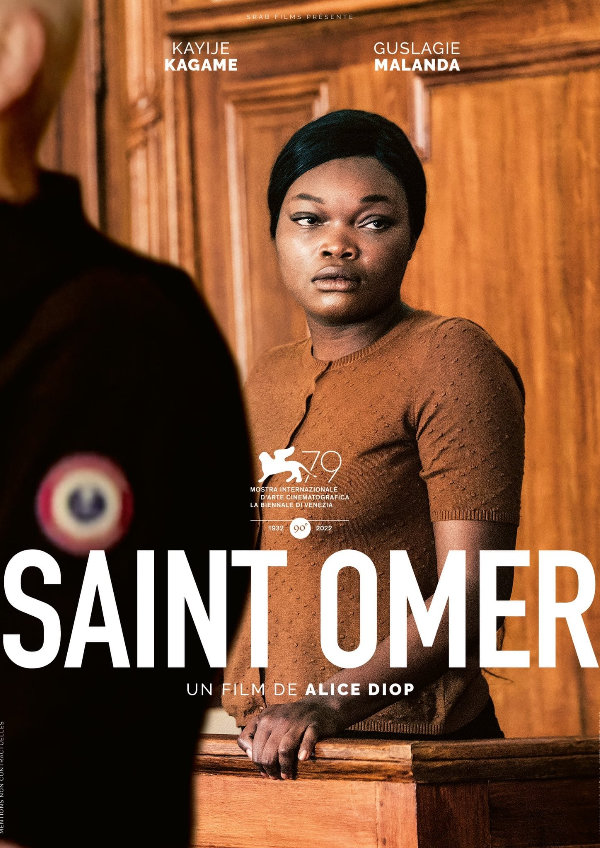

I still haven’t seen any Diop documentaries, but her first fiction feature, Saint Omer, is a classic example of a masterpiece asking questions without providing answers, and one of its best ways of doing so is refusing to cut to a reverse angle whenever one expects it. This is a film carried largely by close-ups and dialogue, and many of its reverse angles are between women in France who never meet, although they do exchange glances at one climactic moment.

It’s devoted to a French trial, based on the real trial of Fabienne Kabo that Diop attended as a curious spectator in 2016, of a well-educated Senegalese woman who left her infant daughter on a seashore to drown, for reasons never clearly articulated (and much of the film’s dialogue comes from the real trial). Diop was pregnant when she attended the trial, and so, we learn eventually, is Rama (Kayije Kagame), a novelist and professor.

Without explaining anything, the film opens with the woman (Guslagie Malanda) carrying her baby daughter to the shore. We cut to Rama being gently woken by her Caucasian French partner from a bad dream in which she was calling for her mother, then to her lecturing a class about Marguerite Duras with a clip from Hiroshima mon amour. (Much later in the film, we also see a clip from Pasolini’s Medea.) The outcome of the trial she attends is never recorded, but the film has generated enough questions by the end to make a verdict seem either impossible or superfluous.

Consciously or not, it carries more than one echo of Ousmane Sembène’s great La noire de… (Black Girl, 1966), which includes comparable details about the alienation and estrangement of a Senegalese woman in France. Sembène’s eponymous heroine is a maid working for a French Caucasian family in Nice; Diop’s woman on trial, an older university student interested in philosophy, has also been living with a white Caucasian male (albeit a much more self-absorbed one), and one who is shown to be as remote from her as she is from him.

Sembène’s title goes to the heart of his subject (with its “de…” clarifying her status as property), but Diop’s title, referring to where the trial occurs, is as indirect as her film. As a rule, commercial cinema relies on closure; this film depends on questions and displacements that never stop.