From the Chicago Reader (February 20, 2004). — J.R.

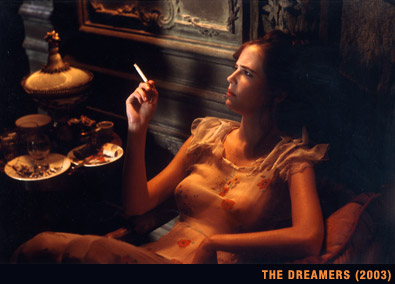

The Dreamers

** (Worth seeing)

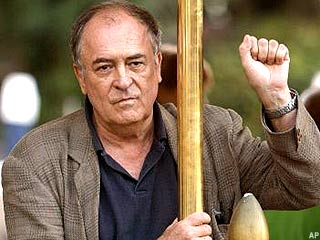

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Gilbert Adair

With Michael Pitt, Eva Green, Louis Garrel, Robin Renucci, and Anna Chancellor.

Nostalgia is highly selective, abridging the past and adjusting it to fit the terms of the present — and often becoming an ideological con job in the process. Those who wax nostalgic about the radicalism of their youth usually imply that the values that made it so attractive back then also make it impossible to hold on to today.

Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, set in Paris over three months in early 1968, focuses on an American student, Matthew (Michael Pitt), who becomes intimately involved with a French brother and sister, Theo (Louis Garrel) and Isabelle (Eva Green), whom he meets at the Cinémathèque. Invited into the siblings’ flat just before their parents leave on vacation, he gets drawn into their perverse and vaguely incestuous games, which combine charades involving movies, sex, and ultimately politics. Their interactions run parallel to the French government’s firing of the disorderly director of the Cinémathèque, Henri Langlois, and the ensuing outcry among cinephiles and filmmakers. Street demonstrations led to clashes with the police — and turned out to be dress rehearsals for the student demonstrations and workers’ strikes that May, which came dangerously close to shutting the country down.

Gilbert Adair wrote the script, adapting his 1988 novel The Holy Innocents: A Romance, which is, unlike the movie, extremely literary. (The main literary device in the movie, Matthew’s offscreen narration, doesn’t exist in the book.) Adair’s earlier Alice Through the Needle’s Eye (1984) and Peter Pan and the Only Children (1987) are highly adroit pastiches of Lewis Carroll and J.M. Barrie disguised as sequels, and many of his later novels are multifaceted hommages — e.g. Love and Death on Long Island (1990) to Thomas Mann and The Key of the Tower (1998) to Alfred Hitchcock. The Holy Innocents was inspired by Jean Cocteau’s Les enfants terribles and is interesting mainly for the wit and invention of the prose — even the incest has a highly literary pedigree. Despite (or perhaps because of) its autobiographical elements, Adair has long been dissatisfied with the book and systematically refused to consider a movie version until Bertolucci came along. (The two are an interesting match: Bertolucci’s cinema tends to be a heterosexual project that flirts with homosexuality, and Adair’s fiction tends to be a homosexual project that flirts with heterosexuality.) Adair has hinted that a revision is coming, and the film contains substantial changes in the plot, though some of them are probably as much Bertolucci’s as Adair’s. Among the additions to the original story are the heroine’s loss of virginity, belying her apparent sophistication, and Matthew’s efforts to separate her from Theo and take her out on a “normal” date — both of which smack of the Freudian revisionism that has been part of Bertolucci’s thinking for some time. Among the more striking deletions are sex between Matthew and Theo, a visit the threesome makes to a castle in Normandy, and Matthew’s death in a street demonstration.

In his unabashedly nostalgic four-star review of the film Roger Ebert, who’s only slightly older than I am, recalls being a tourist in the Left Bank in May ’68 and getting hit with rubber truncheons during a police charge. I checked into a hotel there in mid-June, just after the police had taken back the nearby Odeon Theatre from the student rebels and cleared away the makeshift street barricades, though parts of trees that had been chopped down for the barricades still lay along Boulevard Saint-Michel, and the city still felt strangely energized. I found myself fleeing a police charge one day and getting a potent whiff of tear gas on another. But I remained in Paris for the rest of the summer, moved into a flat in the neighborhood the following fall, and wound up a Cinémathèque regular. Adair, who’d moved to Paris in ’68, was another and became a good friend.

All this might make me too personally invested in the material to view The Dreamers as a movie with some historical value. Ebert apparently assumes that “we” once thought we could change the world, and “we” were wrong. “It is clear now that Godard and sexual liberation were never going to change the world,” he writes. “It only seemed that way, for a time.” But to whom did it seem that way?

Bertolucci’s movie is supposed to show us how great it was in 1968 to be young and horny and in Paris and political and smitten with movies seen at the Cinémathèque. But I was all of those things, and the movie brings back none of my experience. Even the opening details about the Cinémathèque ring false: people are seen smoking in the auditorium, as they’re later seen smoking inside a Paris movie theater (the legendary MacMahon, if I’m not mistaken), but smoking wasn’t allowed in either, as Bertolucci and Adair certainly know. (I was a smoker at the time, as was Adair.)

Of course there’s no reason The Dreamers has to be true to anyone’s experience. I’ve seen the movie twice: two weeks ago in Paris, where it was concluding an unsuccessful run under a somewhat more appropriate English title, Innocents, and a week ago in Chicago. I liked it slightly more the second time — the gaps in plausibility seemed less obvious and consequential, so I could more easily enjoy Bertolucci’s stylish camera moves and editing for their own sake.

But it isn’t in the same category as his much more controlled, accomplished, and beautiful Besieged [see above], which doesn’t have to answer to anybody’s idea of history, or his Last Tango in Paris, the most obvious precursor of The Dreamers, which has a much better cast, cinematographer, score, script, and story. I was reminded of an exchange recounted to me by a good friend of Bertolucci’s in the early 70s, when Last Tango was being prepared: he’d cast New Wave icon Jean-Pierre Léaud in a secondary role, and she asked if people hadn’t already seen enough of this actor. He replied, “Not in Cincinnati.”

In essence, The Dreamers is a fairy tale designed for teenagers in Cincinnati, and I don’t mean this in a snooty way, because teenagers there — and elsewhere, for that matter — could do a lot worse. The only problem is, American teenagers who aren’t 18 technically can’t see it because of the NC-17 rating. NC-17 films traditionally do poor business, and a Variety reporter — knowing that the interests of artists and audiences count for little alongside the bank accounts of industry people — recently chided Fox Searchlight Pictures for not cutting the film to get a better rating. All these kids do is eat, drink, see movies, smoke a joint, bathe together, masturbate, and have sex — until one of them tosses a Molotov cocktail in the final reel. But if Adair and Bertolucci had sliced and diced their characters the way Quentin Tarantino chopped up his in Kill Bill–Vol. 1, The Dreamers might well have been given an R rating.

Reinforcing the sense that Cincinnati teenagers are the target audience is Bertolucci and Adair’s almost abject reliance on every American cliche about the French they can summon up — all the way down to the pseudo-triumphant use of Edith Piaf’s “Non, je ne regrette rien” (with its irrelevant lyrics) over the final credits — and their systematic elimination of all the atmospheric allusions in the novel to Left Bank locations. Still, I’d be willing to accept Bertolucci’s nostalgic fantasy if I could find something believable in the three central characters — their cinephilia, their politics, their nonpolitics, even their by-the-numbers sex. But I can’t.

For one thing, practically all the culture-marking props — paperback copies of The Catcher in the Rye and Susan Sontag’s Death Kit and Trip to Hanoi in Matthew’s hotel room, Theo’s Mao emblems, a Hair LP in the siblings’ flat — are self-consciously and unconvincingly planted. And the casting certainly doesn’t help. Louis Garrel, son of experimental filmmaker Philippe Garrel, manages to speak Adair’s lines as if he’d thought of them himself; he also looks and sounds like a French youth of 1968, and I can even imagine Bertolucci picking him because he looks a bit like Léaud (who’s also seen briefly in this film — in both the past and the present — protesting Langlois’ dismissal, along with his New Wave compatriot Jean-Pierre Kalfon). But Pitt and Green are like clueless fashion models trying to follow a director’s instructions. Worse, all three actors lack the sort of casual rather than studied tenderness American cinephiles of the 60s associated with French actors, especially Léaud and his female costars.

Given the plot, it’s odd that Truffaut’s Jules and Jim is never alluded to in any way, and the references to other movies that are included usually work better for the Cincinnati crowd (with its narrower choices) than for Parisians or Chicagoans (except for the one most American viewers are likely to find inexplicable — clips from the end of Robert Bresson’s Mouchette to contextualize a suicide attempt, which I found offensive). As the film proceeds, the favoring of mainstream movie references extends to Bertolucci’s own oeuvre: the Paris flat reminds me of settings in The Conformist, the incest evokes Before the Revolution and Luna, Theo’s Maoist baggage takes us back to The Last Emperor, a desert tent in the siblings’ flat alludes to The Sheltering Sky, and Matthew’s espousal of nonviolence suggests Little Buddha. Ironically, Bertolucci’s wild and even more cinephiliac 1968 film Partner and his equally radical The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) are excluded. (Bertolucci’s fixation on Green’s balloonlike breasts finds references not only in Maria Schneider’s large breasts in Last Tango but in Jayne Mansfield’s in The Girl Can’t Help It — the movie Matthew and Isabelle see at the MacMahon on their date.)

I’m thoroughly repulsed by the generational one-upmanship in the assumption that if you weren’t lucky enough to be young, in Paris, etc, in 1968 you might as well roll over and die. “I don’t know about you,” my oldest French friend said to me two weeks ago, “but I sure wasn’t having a great sex life in May 1968.” If my sex life improved once I moved to Paris, it was mainly because French culture taught me ways of finding pleasure with less guilt — May ’68 had little to do with it. And however much I might nostalgically boast about the police charge and tear gas in June ’68, they were tokens of a failed revolution.

In a 1985 essay filmmaker and film theorist Thom Andersen cites Robin Blackburn’s observation that middle-class sociology begins to understand modern revolutions only when they fail; he then goes on to say that this applies equally to dramatic art and that films such as The Battle of Algiers, Burn!, and Viva Zapata! idealize and glorify political defeat. The only concern of The Dreamers is its wistful nostalgia, and so it celebrates the failed revolution of May ’68 without even bothering to record its failure, much less analyze it. (Adair’s novel is even worse, insofar as it ends by sentimentally commemorating Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses and its dedication to Langlois. In fact, Langlois got his job back; the students and workers were less successful.)

Narcissism has always played a more important role in Bertolucci’s eroticism than collective sentiment of any kind — including three-way sex or the more sweet-tempered arrangements of Jules and Jim — and Matthew placing a snapshot of Isabelle inside his underpants next to his erect penis is the perfect encapsulation of Bertolucci’s idea of a turn-on. It’s this sort of narcissism, multiplied by three, that ultimately makes this trio so charmless–they certainly don’t represent any of the things that lured me to Paris or kept me there. Among the things that did was rediscovering America and American movies through the lens of France and seeing how French cinema helped mold American movie culture. And I should point out that the French love of America reflected in the plot of The Dreamers, and Godard’s Breathless before it, continues unabated, even if the American love of France appears to be on the wane. In Paris I visited a shop that sold educational materials for high school teachers, among them DVD study guides for Bowling for Columbine and Elephant. I didn’t buy either but did pick up a special edition of John Ford’s The Searchers that included a documentary about McCarthyism, interactive puzzles about Ford’s camera-angle choices, and other features I’d never expect to find on any American DVD of the film. That same week the cover story of Les Inrockuptibles, a fashionable French arts weekly, was devoted to the efforts of anti-Bush Americans such as Michael Moore and Al Franken.

I don’t mean to imply that France could teach us the same things it did 30-odd years ago, or that Bertolucci’s fantasy can’t serve other needs and whims. But its nostalgia and narcissism are ultimately two versions of the same thing, and neither can reopen cross-cultural channels. Instead they keep this story stuck in the past, frozen and intact and irrelevant. I’d much prefer a fantasy about sex, politics, cinema, or some version of all three that teaches us something new about the present.