From the Chicago Reader (August 30, 2002). — J.R.

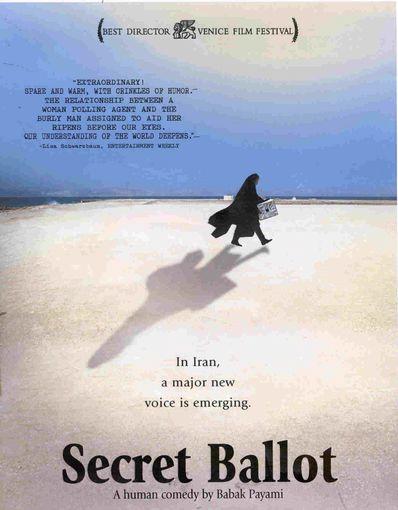

Secret Ballot

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Babak Payami

With Nassim Abdi, Cyrus Ab, Youssef Habashi, Farrokh Shojaii, and Gholbahar Janghali.

Secret Ballot is…a demonstration of the fact that society at large has much more integrity than the forces that govern it. This is as true in Iran as it is in the United States. — Babak Payami

I’m embarrassed to admit that I was one of the people who fell for the story that circulated not long after the invasion of Afghanistan that George W. Bush had asked to see a subtitled print of Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar. It was sheer wishful thinking, the result of a hope that sympathy for the innocent Afghan victims of the American assault would somehow prevail over all the confusion and self-righteousness.

The sources of the rumor soon went silent, but it had already circled the globe. I searched the Internet and turned up allusions to it in France’s L’Humanité, Britain’s Guardian and Observer, and Australia’s The Age, as well as in Brazilian and Dutch papers. (Some of them did add the safety net of “reportedly” or “apparently.”) A recent piece about Iranian cinema in the London Review of Books by Gilberto Perez notes, “The truth was that an attempt was made to arrange a screening for [Bush] in the hope that if he saw it he might take a more humane view of the Afghans.” In other words, an effort to get the White House interested had been translated into a request on the part of the White House.

When I finally caught up with Secret Ballot at a film festival last month I decided that this, not Kandahar, was the movie Bush should see. It’s not only considerably more polished and entertaining (if less experimental and poetic), but it has more to teach Americans, especially because it shows how certain old-fashioned American values — in particular an idealistic view of democracy and free elections — survive in Iran today.

Was this wishful thinking as well? A second look at this road movie made me think yes and no. Yes because Iran isn’t entirely a democracy and because Bush would never want to see this movie in a million years. (He’s on record as being especially fond of The Rookie and Austin Powers in Goldmember, whose obsession with fathers and sons — especially the villain’s beloved Mini-Me — must have made it an obvious choice.) No because Babak Payami, the film’s writer-director, is perfectly aware that Iran isn’t entirely a democracy and is using idealism about democracy and elections as only one element in a complex and nuanced argument addressed to people outside as well as inside Iran, and because Secret Ballot, which unlike Kandahar isn’t an art film, is opening at multiplexes.

The multiplex in Chicago is Landmark’s Century Centre, which makes it the venue for the two most entertaining and well-crafted Hollywood movies — generically if not technically — I’ve seen lately, the other being the German film Mostly Martha. Part of what makes these films Hollywood comedies is their ability to please a wide variety of viewers, not just an art-house crowd. The same holds for other recent Landmark selections, including Amelie, Y tu mama tambien, and The Fast Runner (Atanarjuat) — movies whose ability to hold an audience is so great the fact that their characters aren’t speaking English scarcely matters, though it will still keep such movies out of most other American multiplexes.

At the start of Secret Ballot a mysterious object, which we subsequently discover is a ballot box, drops by parachute from a military plane. It’s just after dawn on a beach on Kish Island — a deserted island in the Persian Gulf that was declared a free-trade zone in 1993 and was where Marziyeh Meshkini’s The Day I Became a Woman was shot. A soldier (Cyrus Ab) enters frame left and retrieves the box, then approaches freestanding bunk beds, wakes a fellow soldier in the lower bunk, and asks him what the box is for. (All of the actors are nonprofessionals, and given the naturalness of their performances, it’s surprising that Payami shot this film without rehearsals.) Before going back to sleep, the soldier explains that it’s election day and an agent he’ll have to escort will turn up at eight to carry the box around to voters.

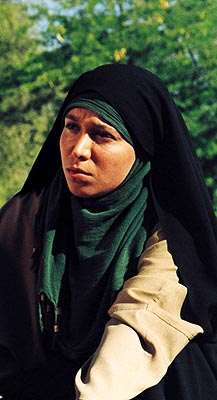

“It’s 8:15,” complains the first soldier. “Where is he?” He builds a fire, and soon a motorboat enters frame left, just as he did, and a nameless young woman (Nassim Abdi), barefoot and in a chador, gets out. Telling the people on the boat she’ll be back at five, she rolls down her trousers, puts on socks and shoes, walks over to the box, and studies a map. When she shows her official order to the soldier, he initially claims it’s no good because it doesn’t say anything about a woman agent. She asks to see his ID, which he has to show if he wants to vote, and he explains that his buddy’s sleeping on top of it. She replies brusquely, “OK, you can vote later.”

The screen credits say this film was based on an idea by Makhmalbaf, whose 2000 pseudodocumentary “Testing Democracy” — about the same national election, in 2000, also set on Kish Island — included a woman parachuting down along with a ballot box. Shown at the Chicago International Film Festival two years ago as half of the feature Tales of an Island, “Testing Democracy” [see below] is mainly an extended metaphor about digital video — celebrated in the film because of its similarity to a pen– as a democratic form of cinema.

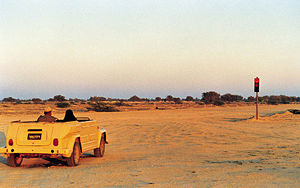

Generally Payami uses surrealism much the way he uses a form of realism — as a means of positioning his audience so that we become subjective participants in the action and not merely neutral bystanders. His realism uses not only natural locations and nonprofessional actors, but long shots and extended takes, both of which give the viewer time as well as space for observation and reflection. His surrealism tweaks verisimilitude to position his characters in order to make points about them; in one extended gag the first soldier stubbornly obeys a traffic sign in the middle of nowhere that clearly has no reason for being there.

Payami also uses sound realistically as well as surrealistically, for related reasons. The excellent original score, by Michael Galasso, is pointedly neither Iranian nor Western in any obvious way — Payami has stressed that he wanted to avoid any ethnic specificity — and the extremely sophisticated sound design of Michael Billingsley (who also worked on Last Tango in Paris) manages to convey a realistic sense of presence while subtly nudging us at times in other directions. (The most striking unrealistic use of sound occurs during a sequence in which three men who’ve traveled a considerable distance to vote complain that their candidates aren’t listed on the ballot; they’re the only people we see, but we hear women’s voices too.)

After the film’s opening sequence the soldier puts the ballot box in a jeep, the agent gets in the back, and they start off through the desert. Their conversation makes it evident that he’s a rube. “Who has to vote?” he asks, and she explains that no one’s forced to. When they sight a man running in the distance he concludes it must be a crook, but she thinks the man’s afraid of the army jeep. As soon as they catch up with the man, the soldier orders him at gunpoint to empty his pockets. She apologizes to the man and eventually persuades the soldier to put away his rifle. While the two men continue to voice their hostility, she shows the man a list of the candidates and asks him to make two choices.

By now it’s clear that this movie is a comedy of contrasting manners — soldier’s and agent’s — evoking the friction between straitlaced Katharine Hepburn and jaded Humphrey Bogart in The African Queen. It’s also clear that the conflict between this duo precisely reflects the principal social and political division in contemporary Iran, between the ruling fundamentalists (a minority) and the governing reformists (a majority) — a division that’s also generational, because 65 percent of the mainly reformist populace is under 25.

It’s interesting that males in Iran can vote at 14, females at 16; one could argue that might make Iran more democratic than America, at least insofar as the electorate is more representative of the overall population — though females are, as usual, less than equal. (One adult in the film questions why girls can’t vote at 12, since they can get married at that age.) Yet evaluating the democratic institutions of Iran by comparing them to this country’s doesn’t get one very far, because the variables are so different. Still, it’s fun to speculate how Bush would relate to a movie like Secret Ballot. Would he identify more with the idealistic election agent, who’s obsessed with the idea of getting every eligible citizen to vote, regardless of whether they know whom they’re voting for or even if the choices are meaningful? Or would he identify with the soldier, who mistrusts everyone on principle? Would he agree with the soldier that democracy comes out of the barrel of a gun? Or would he agree with the agent that those gun barrels make democracy relatively meaningless? It’s pertinent that the Florida vote counting that preceded Bush’s taking office occurred while Secret Ballot was in production. “In fact,” Payami told the U.S.-based Iranian critic Jamsheed Akrami, “I added a scene to Secret Ballot that was to remind the audience of the Florida events deciding the election. I will not disclose which scene it is!” (Maybe the Landmark could promote this movie with a contest seeing who can come up with the right scene.)

Payami was born in Tehran, but moved with his family to Afghanistan when he was 7, and returned to Tehran after the 1979 revolution, when he was 15. He moved to Canada soon afterward, majored in cinema studies at the University of Toronto, then worked as an interpreter, tutor, legal clerk, and software developer. In 1997 he moved back to Iran, where he made his first feature, One More Day (2000). I haven’t seen that film, but it seems to anticipate the plot of Secret Ballot, judging from the description offered by Leslie Camhi in the New York Times: the story of a developing relationship between a man and a woman in Tehran who meet at a bus stop each morning and ride together on the bus “separated by the metal rod that divides the men’s and women’s sections.” By the end of Secret Ballot the two characters have become somewhat friendlier — there are even hints of romantic attraction — and the soldier even decides, with typical denseness, to cast his vote for the agent.

Part of the agenda of most Hollywood movies is to appeal to as wide a constituency as possible, which makes them mean different and sometimes even antithetical things to different segments of the audience. (Apocalypse Now is a classic example, making its pitch about the Vietnam war to hawks and doves alike.) Secret Ballot, which was financed partly by European sources, had to get past Iranian censors before it could be shown in Iran (where it was well received, at least at a festival showing), though according to Payami, no alterations were necessary. Hollywood features commonly get revised by producers before and after test marketing, so one could argue that Payami had more freedom to work out his artistic vision than his Hollywood counterparts — unless he was censoring himself.

I see Payami as creating a formal relationship between his audience and subject that encourages us to be open-minded: neither of the two main characters can be seen as all right or all wrong — a humanist position more than an ideological one (though humanism is of course an ideology). This apparently doesn’t wash well with commentators who seem to think that an Iranian film about elections is of necessity propaganda — a few of whom have concluded that since Secret Ballot isn’t an unambiguous statement in favor of democracy, it must be a gift to the mullahs. Yet the soldier’s overall cluelessness about democracy and the people he encounters makes him the butt of more gags than the idealistic agent, though both positions are challenged by the film. When the agent is snubbed after walking into a funeral ceremony that women are expressly forbidden to attend, Payami implicitly asks us to decide which is better, obeying reactionary gender laws or defying them and offending the mourners.

An extended episode in which the agent tries to enlist voters in a remote settlement lorded over by an unseen matriarch known as “Granny” suggests that democracy and voting become meaningless in such a social context. But it would be shortsighted to assume that neofeudal backwaters of this kind can be found only in Iran or the Middle East, and Payami’s allusion to the Florida elections makes it clear that this movie is about more than Iran. Axis-of-evil types are everywhere.