From American Film (September 1978). -– J.R.

Talking about avant-garde film these days raises a quandary. For one thing, no one can agree on precisely what the label means. Start by asking the proverbial man on the street what an avant-garde movie is. Chances are, if you don’t get insulted, the description that’s offered won’t exactly be a heartening one.

On the other hand, address your query to “an avant-garde filmmaker,” and you’re just as likely to get a moralistic distinction between art and commerce — or between art and entertainment calculated to shrivel your own sense of seriousness to the size of a pea.

The fact that there are such disagreements about simple definitions only helps to keep the term loaded and half-cocked. A Cuban director at a film festival once allegedly shunned an American director’s gesture of friendship by saying, “I only talk to people with guns. My film is a gun; your film isn’t. ” In analogous fashion, the mere concept of avant-garde film is often used as a gun by friends and foes alike. This scares off countless spectators who fall in between these categories — less committed souls who understandably run for cover as soon as any shots are fired.

We can describe avant-garde cinema in social terms much more easily than we can define it materially. Patrons and foundation grants help to support it , art museums and specialized showcases exhibit it, and most well-known film critics tend to avoid it like the kiss of death.

Trying to account for this neglect, we can come up with several explanations. For starters, avant-garde films are notoriously difficult to write about. Because they lack the widespread ad campaigns that are launched for commercial movies, it’s easy enough to assume that most filmgoers wouldn’t go out of their way to see such films. And, like a vicious circle, the lack of attention paid by critics only helps to ensure that audiences do stay away.

Occasionally a critic of note will suffer through a representative sampling of avant-garde fare and emerge with complaints of boredom and pretentiousness. More often than not, such charges are perfectly just. Yet as science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon once pointed out in reference to his own profession, ninety percent of everything is trash. Why should avant-garde filmmaking be any different? And what about the ten percent that matters?

The problem with a category like avant-garde is that it may ultimately tell us more about packaging than it does about either the art’s products or its practitioners. By focusing on three exceptional figures in the North American avant-garde — Jon Jost, Yvonne Rainer, and Michael Snow — I want to demonstrate that the category they share is scarcely adequate for any clear sense of their accomplishments. On the contrary, the term mainly helps to account for why their exciting and pleasurable movies remain relatively difficult to see.

***

Consider thirty-five-year-old Jon Jost, to start with the least-known and perhaps the most accessible of the trio.A defiantly independent and politically radical filmmaker who has completed four features and eighteen shorts since 1963, he has yet to receive even a fraction of the attention he deserves.

Jost traces his political radicalization to the twenty-six months he spent in a federal penitentiary as a draft resister in the mid-sixties. After his release, he worked with draft resistance and neighborhood organizing groups in Chicago (his birthplace), and was instrumental in establishing the Chicago office of Newsreel, the celebrated leftist filmmaking collective that was particularly active in the sixties.

At the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Jost became disillusioned by “the romantic militancy of the street mobs, the mindlessness of mass psychology, the willingness of the movement leaders to utilize the same media fakery as ‘the enemy.'” He departed for California and embarked on a different sort of political filmmaking with such shorts as A Turning Point in Lunatic China and 1,2,3, Four.

His true coming of age as a filmmaker can be seen in his first feature, Speaking Directly: Some American Notes, which he shot in Oregon and Montana in 1973. A candid and challenging self-portrait, it carries autobiographical directness and political rigor a lot further than one might have thought they could go in a film. It achieves this by centering not only on Jost’s life but also on the audience’s precise relationship to his life through its experience of the film itself.

An early taste of what Jost is up to comes when he addresses the camera and the invisible spectator in the following way: “This is a movie, a way to speak. It is bound like all systems of communication with conventions. Some of these are arbitrarily imposed, some are imposed by economic or political pressures, some are imposed by the medium itself.

“Some of these conventions are necessary: They are the commonality through which we are able to speak with one another in this way. But some of these conventions are unnecessary, and not only that, they are damaging to us, they are self-destructive. Yet we are in a bad place to see this,” he concludes with devastating irony. ” We are in a theater. ”

Starting from this premise, Jost proceeds to introduce us to his personal life on the one hand (with friends, lovers, and Oregon neighbors) and his political reflections on the other (on America’s power, institutions, and domestic and foreign policies). Moving back and forth between these subjects to keep them constantly interrelated, he creates a fusion of elements that is startling in its degree of honesty and awareness.

Thus, he not only tells us about the former girl friend who financed the film, but also informs us of the surprisingly low production cost (between $1,500 and $2,000) and shows us the equipment used in shooting it. He adds that “this by itself falsifies by omission,” leaving out both the lab equipment and the ” vast complex of processes required to produce these things. Such a picture would need to show the world: the iron ore pits of Minnesota; the steel mills of Gary, Indiana; the gold mines of South Africa; a camera factory in France — to mention just a few things. ”

A master technician, Jost includes everything from elaborate long-take interviews to animation and optical mixing. Often merciless and humorous about himself as well as those he films, he even lets a skeptical friend urge the audience to burn the print of the film they’re watching.

Apart from some screenings abroad, virtually the only public showings of Speaking Directly to date have been door-to-door affairs, with Jost confronting audiences “directly” as well as filmically. The fact that he still handles the U.S. distribution of all his films probably helps to explain why this feature hasn’t been seen more widely. Yet, as an object lesson in how a professional, entertaining , and serious feature can be made on the meanest possible budget, it could be studied to advantage by film students everywhere.

In the three features Jost has made since, one can find an overall escalation in budgets and a movement toward fictional narrative in an attempt to broaden his audience. Angel City, which cost a little under $6,000, is a comic detective story featuring a wisecracking variant of Philip Marlowe and Lew Archer named Frank Goya, whose investigation of a murder is set against a detailed economic and social critique of Los Angeles. Broader and more misanthropic in its humor than Speaking Directly, it includes such sequences as a screen test for a Hollywood remake of the Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will.

Last Chants for a Slow Dance (Dead End), which cost only $3,000, dispenses with fantasy and satire to create a somber and realistic portrait of an alienated trucker. Paradoxically. Jost’s first extensive venture in sustained storytelling contains long-take sequences, which suggest some of the preoccupations of nonnarrative or “structural” filmmakers like Michael Snow, linked by country and western songs that are ably composed and performed by Jost himself.

Chameleon — Jost’s most recent feature, which I haven’t yet seen — had a lavish budget of $35,000 and clearly represents his bid to hit the big time. Whether or not he makes it, the lessons of his career remain. As avant-garde filmmaker Louis Hock has pointed out to me, Jost’s versatility ensures that his films can be enjoyed for a lot more than their politics.

Formally, Jost has developed from an iconoclast with many resemblances to Jean-Luc Godard to something of a homegrown wizard with a distinct sensibility of his own. Politically, one could say that by avoiding conventional rhetoric and sticking to concrete observations he is more sophisticated than Godard — who, by the way, has been quite vocal in his support of Jost’s work.

***

Dancer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer has a very different sense of the political impact of her own films. “No matter how overtly politicized my work becomes with respect to subject matter,” she has said, “my thinking and making process will always result in a product that appeals to a very select audience, an audience already disposed to share my point of view and appreciate the manner in which it is conveyed.”

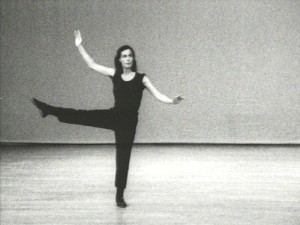

Born in San Francisco in 1934, Rainer had a long and fruitful career as a dancer and choreographer before she started to experiment with short films in the late sixties. She has subsequently dismissed these initial forays as “a boring hybrid, too obvious and simplistic to work as either film or dance, ” and indeed her reputation as a filmmaker essentially rests on her three features, all of which were made in the seventies.

There are at least two ways to approach the intricate, seductive complexities of Lives of Performers (1972), Film About a Woman Who… (1974), and Kristina Talking Pictures (1976). You can come steeped in background information about Rainer’s innovative dance work in New York and elsewhere (Dusseldorf, London, Paris, Rome, Spoleto, Stockholm), or you can come steeped in the avant-garde climate she has usually been associated with: Merce Cunningham, Phil Glass, Robert Rauschenberg, and a host of others.

Alternately, you can walk into her movies without any of this knowledge — which probably approximates the experience of most of her audiences. And if part of what you see and hear puzzles you, you shouldn’t conclude from this that the ” experts” are having an easier time of it. As ironic as it sounds, obscurity and ambiguity aren’t so much obstacles to an appreciation of her films as integral parts of their enjoyment.

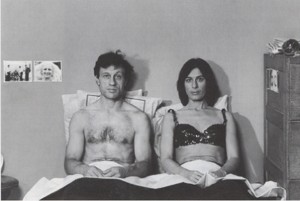

Take Lives of Performers, which mixes autobiography and fiction in several tantalizing ways. After we watch edited footage of Rainer rehearsing with her dance company for a performance, we’re shown photographs of another performance while we hear the dancers describe their intimate relations with and feelings for each other at the time.

As the film progresses, we are treated to other blends of fact and fancy. While we see the performers in a studio, we hear them describe their real or imaginary emotions off-screen, this time in commentaries that were partially recorded during some of the dance company’s performances. At the end, we ‘re presented with a complete performance by the group that is composed of tableaux, all of them based on stills from G. W. Pabst’s silent film Pandora’s Box.

Film About a Woman Who..., my own favorite of Rainer’s features, expands on the playful enigmas in Lives of Performers. For one thing, we can never be quite sure when the male and female narrators off-screen connect — or don’t connect — with the characters that we see. To complicate matters further, the film bristles with so much visual and verbal wit that we can never quite disentangle conscious clichés from sincere expressions — in the voices, images, and printed titles alike. What we get instead of a straight story is a sort of kaleidoscope of split-level texts and crisscrossing story threads that perform a teasing dance of their own.

Throughout this gracefully organized confusion, the stamp of Rainer’s strong personality is everywhere. Like Jost, she has the flavor of a distinctive stylist, although the style itself, and the life-style it depicts, couldn’t be more different. In contrast to Jost’s down-home, cracker-barrel approach, her movies inhabit the underground reaches of a very self-conscious urban milieu, closer to the territory of a Woody Allen or an Elaine May.

Part of the visual impact of Rainer’s first two features can be attributed to the stunning black-and-white photography of Babette Mangolte, an accomplished French cinematographer who has also worked with avant-garde filmmakers Chantal Akerman, Marcel Hanoun, and Michael Snow. But just as much is due to some of Rainer’s wackier visual ideas: her own face plastered with patches of newsprint, all declarations of love, which the camera scans like an inquisitive fly; a sequence of stills illustrating the celebrated shower murder of Janet Leigh in Hitchcock’s Psycho, accompanied by Rainer’s voice reciting a text about a woman who is sick and lost.

In Kristina Talking Pictures , her first color feature, Rainer comes much closer to telling a single story, about Kristina, a lion tamer from Europe who comes to America, takes up choreography, and has an affair with a man named Raoul. But anticipating a strategy that was taken up later by Luis Buñuel in That Obscure Object of Desire, she uses not one but several actresses — including herself — to portray the heroine.

In all her features, Rainer combines intellect, poise, and deadpan humor in a way that continually reminds one that the brain and the vocal cords are both parts of the body. (It seems hardly coincidental that one of her major dance pieces is entitled The Mind Is a Muscle.) Her sharp feeling for pop banality and incongruity crops up everywhere. We find it in a couple’s romantic grope on a seashore strewn with driftwood in Film About a Woman Who…,affording a deadly parody of popular “salon” photography in the fifties.

Throughout the humor and the profusion of diverse images and texts — which often make her films resemble annotated, semi-fictional scrapbooks — there’s a serious, underlying theme of female victimization and a perpetual meditation on the dual nature of performers, whether on stage or off. Weaving together material that is both public and private, Rainer creates an elusive, scintillating tapestry that invites us to contribute our own connecting threads in order to complete the design.

***

Michael Snow’s films also invite creative participation from the audience, but of a very different sort. One of the most respected and influential avant-garde filmmakers in North America today, Snow eschews the practice of storytelling almost entirely — a fact that undoubtedly explains why some moviegoers have declared his films to be virtually unwatchable.

Yet all of Snow’s best films are concrete adventures of one kind or another. And if they bypass some of the imaginary ingredients found in ordinary movies, this is only so they can concentrate all the more intensely on their own concerns — exciting matters in their own right.

A Toronto-based Canadian in his late fifties, Michael Snow worked as a painter, sculptor, photographer, jazz musician, and animator before seriously embarking on films of his own. Even today, after his major films have earned him an unrivaled status within the avant-garde, he devotes most of his time to playing in a free-jazz group. His last film — an engaging, humorous short called Breakfast — was made more than two years ago.

Some followers of Snow’s career have speculated that the reason for this change of focus is that his most important films have virtually exhausted their unique subjects. In other words, having taken certain forms of exploration as far as they can go, Snow is in the unenviable position of an astronaut having just returned from an exhaustive tour of the solar system. Where can he go next?

Wavelength (1967) — his first major film, and probably his best known — still provides an ideal introduction to his work. A relentless forty-five-minute voyage across an eighty-foot loft through a series of short forward zooms, it is a film that unceasingly transforms, questions, and illuminates everything in its path.

Although a veritable library of debate has already accumulated around the issue of whether this camera journey actually constitutes a “story” or not, there is little doubt that the attentive spectator is experiencing something very close to one. The essential difference may be that while most filmmakers place their stories on a screen, Snow stages his within the dynamic process of spectators watching the film– making us, not the actors, the heroes and protagonists of his staged adventures.

This process in Wavelength can be described in several ways. On one level, it is the unraveling of a simple mystery: Where is the zoom headed, and why? When it starts out, most of the loft — including four double windows, some furniture, and a radiator — is still clearly visible. But as the field gradually narrows, three small pictures on the opposite wall become more prominent, and we eventually perceive one of them as the camera’s destination. It isn’t until the film’s final moments, shortly before this photograph fills the frame, that we can identify its subject as sea waves.

On another level, the film is responding to a more philosophic question — namely, What is a room? (Manny Farber, the first critic to write about Wavelength, remarked, “If a room could speak about itself, this would be the way it would go. “) If the above “synopsis” makes the film sound like a minimalist exercise, it is a misleading one. For while the zoom lurches forward, the room passes through dramatic changes of light, color, texture, and grain, as well as perspective, altering and enriching our grasp of everything that we see.

While sudden shifts in the time of day keep our sense of overall time suspended, four separate “human events” give us recognizable chunks of real time. The first two, relatively mundane, involve the moving of a bookshelf and two women listening to a Beatles song on the radio. Later on, after we hear the off-screen sounds of glass splintering, a door being forced open, and footsteps, a man staggers into the frame and immediately drops dead, just before the zoom darts past him. And toward the end of the film, a woman enters the frame to telephone a friend about the corpse she’s just found on the floor.

By the time the camera has arrived at the photograph of sea waves — and Snow has complicated his trajectory further by superimposing earlier parts of the film over this image – a sine wave on the sound track, which has been progressing since the beginning of the film from its lowest to its highest frequency, is joined by the sound of a police siren.

Where have we traveled in forty-five minutes? Snow offers at least two playful explanations of his own: “A pun on the room-length zoom to the photo of waves (sea), through the light waves and on the sound waves.” And: “The space starts at the camera’s (spectator’s) eye, is in the air, then is on the screen, then is within the screen (the mind).”

The title of Snow’s next important film, completed in 1969, isn’t verbal but graphic: a horizontal double arrow pointing in opposite directions. For the sake of convenience, it has been subtitled Back and Forth. Set inside a classroom that’s alternately empty and inhabited, it sculpts its own kind of space with a swiveling pan that’s as relentless as the zoom in Wavelength.

This back and forth motion, which resembles the twist of spectators’ heads at a tennis match, begins quite slowly, and gradually accelerates until the room itself becomes a blur. Then it shifts briefly to a vertical pan that gradually slows down, before the film concludes with a series of superimposed “flashbacks” of earlier portions.

Partially an examination of what happens to our visual perception in relation to different velocities — an interest that can be traced all the way back to the studies of Eadweard Muybridge and other film pioneers — Back and Forth functions as a kind of dialogue between the camera’s eye and the spectator’s eye. Paradoxically, while it uses people and objects in the way that a painter might, it also transforms these static “painterly” subjects into paroxysms of movement and energy.

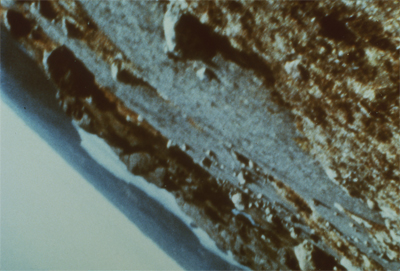

In many respects, Snow’s most ambitious experiment in camera movement remains La région centrale, completed in 1971. This time, the task that he set for both the camera and the spectator is considerably more arduous. Learning to submit to its rigors, however, can prove to be even more invigorating and liberating. Having seen this film only once, several years ago, I can only hark back to my experience of it at the time, which was difficult, physically exhausting, and mind-boggling.

To make La région centrale, Snow had to design a machine with the help of Pierre Abbaloos that could program the camera’s movements without any direct human contact through the use of sound tapes. This machine was then installed on a remote mountain plateau in Quebec, reachable only by helicopter, where Snow and his crew hid from camera range while the film was shot.

Snow explains the procedure as follows: “The camera moves around an invisible point completely in 360 degrees, not only horizontally but in every direction and on every plane of a sphere. Not only does it move in pre-directed orbits and spirals, but it itself also turns, rolls, and spins. So that there are circles within circles and cycles within cycles. Eventually there’s no gravity. The film is a cosmic strip.”

One might add that the speed of the camera movements also varies considerably. In short, for the hardy and fearless it’s even more of a workout than the Space Mountain ride in Disneyland or the average roller coaster. It lasts three hours and has been described as the first real landscape film. The sound track consists of the tapes used to monitor the camera’s movements.

Perhaps the most awesome and challenging aspect of the movie is the degree to which the camera performs operations that no human eye could approximate. Tracing out portions of a spectacular vista, it’ s a journey that fluctuates from the contemplative to the demonic. But as Snow describes it, “You are here, the film is there. It is neither fascism nor entertainment. ”

What is it, then? An investigation of human and nonhuman perceptions, one could say, in which scientific and aesthetic principles become endlessly intertwined. One can come to terms with it comfortably only by freeing oneself from the strict identification with the camera that most movies require on one level or another. And the process of this acclimation becomes an education that can teach one volumes about the spatial and psychological assumptions that we usually bring to films.

***

Clearly, the differences between Jost, Rainer, and Snow ate enormous. But it shouldn’t be concluded from this that they represent the only important directions that recent avant-garde filmmaking has taken. At most, they figure as three particular flower patches in a burgeoning garden that no single article could begin to do justice to.

And what about the remaining ninety percent of dull, synthetic avant-garde films that I mentioned at the beginning? Like the ninety percent of most things that clutter up our days, they will continue to be around, scaring off critics, discouraging many spectators, and perhaps inspiring a few others. The important thing is not to confuse them with the valuable ten percent — or whatever precious fraction — that we don’t get enough chances to see.