This was written in 1982 for The Movie: An Illustrated History of the Movies in the U.K. — J.R.

Starting with Gradisca, a local beauty, lighting a torch and setting a bonfire ablaze to roast the ‘winter-witch’ and usher in the spring, and ending with the wistful farewell she bestows a year later on the randy teenage boys at her wedding while sadly tossing away her bridal bouquet, the small-town life celebrated by Amarcord is above all one of community rituals and seasonal changes. Within this basic rhythmic pattern of eternal recurrence, dreams and other fantasies play as much of a role as precise recollections.

Amarcord means ‘I remember’ in the regional dialect of Rimini (Fellini’s own hometown), and even though the director has been at pains to disclaim any specific autobiographical intent in this episodic caravan or burghers and small-town events, it is clear enough in Fellini’s work as a whole that fact and fancy are never very far apart. Amarcord is Fellini’s thirteenth feature as a director, made 20 years after his first treatment of male adolescence in I Vitelloni (1953, The Spivs), and the distance he has traveled since is largely a matter of the extent to which he has learned to trust imagination over ‘realistic’ observation. Thus the strange white fluffy substance that drifts through the province every spring is neither less magical nor less ordinary than the mysterious local snowfall, which can easily beat the cinema as an evening’s main attraction. And the pomp and circumstance so inextricably intertwined with the ceremonies of church and state — funerals, weddings, and public rallies — are carried over into the less formal, local pastimes which sometimes merely involve standing around and gawking.

Unavoidably the rites of puberty and the spectacle of politics -– climaxing in the ecstatic figure of the blonde nymphomaniac Volpina or the charismatic Mussolini -– testify to the same tortured libidos. It is worth noting that the privileged sector of Fellini’s poetic kingdom, like that of Jacques Tati, is always the town square and public forum where diverse personalities are allowed to pass and mingle. Privacy scarcely seems to exist at all in a community ruled by gossip, rumor, and myth, yet it is precisely the domauin of privacy that the town’s collective dream life feeds upon –- sexual extravaganzas that, like the cinema itself, seem to rely on intimacies denied to most citizens.

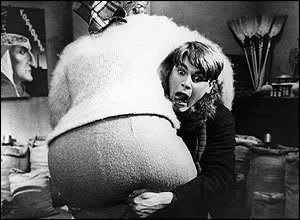

Some critics have objected to the vulgar directness of the scatalogical and sexual humor in Amarcord. The latter includes such moments as the brief encounter between Titta and Luccia, the tobacconist who invites him to suck her enormous breasts after he has demonstrated his youthful prowess by lifting her hefty body several times…until she proves too much for him. Yet Fellini’s bawdy -– tied in this case to his background as a cartoonist –- is merely the reverse side of his sense of pathos, which comes to fore with Titta’s mad Uncle Teo, who climbs a tree and refuses to budge because he doesn’t have a woman at all.

It is typical of Fellini’s style, supported by Nino Rota’s bittersweet score, that his characters always seem to wind up with too much or too little -– perpetually stuck, as it were, between the mud and the stars. Subjective memory can distort, flatten, contract or expand whilst, at the same time, recollection remains in innocent awe of spectacles as diverse as an ocean liner at night (the magisterial Rex, framed by beautifully backlit sets) and a Fascist rally.

Amarcord was the fourth of his features to win an American Academy Award for best foreign film, and it is not hard to see why. The garrulous lawyer who intermittently serves as the film’s narrator and local guide reminds us that much of what we see is peculiar neither to this time nor to this town; the film charts the lot of provincial dwellers everywhere, and Fellini has been true to this principle by fashioning a movie for, as well as about, his home-town cronies. Refugees of small towns — as well as those who still live in them -– will find parts of their experience writ large in Fellini’s earthy sketches. JONATHAN ROSENBAUM