A column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, printed in their March 2023 issue (#170).. — J,R.

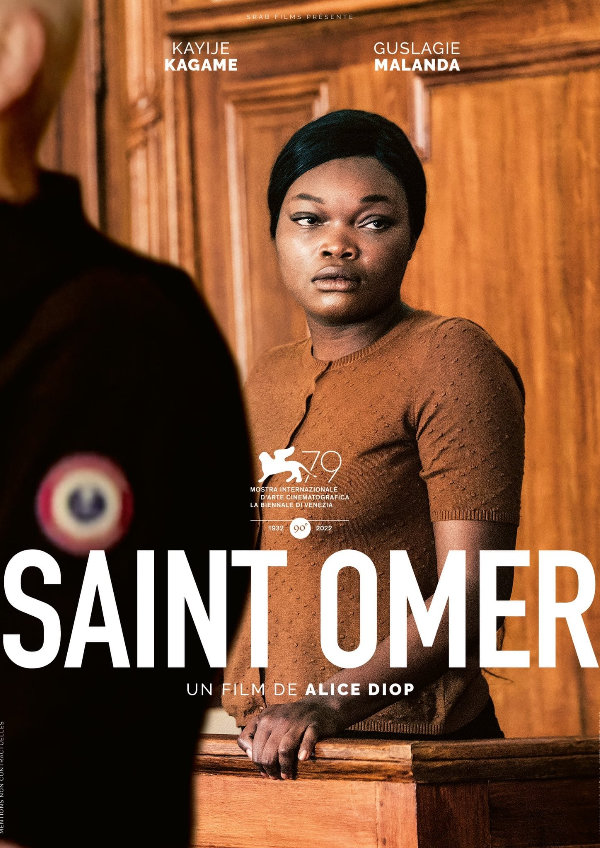

It’s because I don’t understand this woman, because I didn’t understand her at the trial, and I still don’t understand her now….That’s what I offer to the viewer—to ask him or herself questions.

Alice Diop

I still haven’t seen any Diop documentaries, but her first fiction feature, Saint Omer, is a classic example of a masterpiece asking questions without providing answers, and one of its best ways of doing so is refusing to cut to a reverse angle whenever one expects it. This is a film carried largely by close-ups and dialogue, and many of its reverse angles are between women in France who never meet, although they do exchange glances at one climactic moment.

It’s devoted to a French trial, based on the real trial of Fabienne Kabo that Diop attended as a curious spectator in 2016, of a well-educated Senegalese woman who left her infant daughter on a seashore to drown, for reasons never clearly articulated (and much of the film’s dialogue comes from the real trial). Diop was pregnant when she attended the trial, and so, we learn eventually, is Rama (Kayije Kagame), a novelist and professor. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 492). — J.R.

Short and Suite

Canada, 1959 Directors: Norman McLaren, Evelyn Lambert

Dist—BFI. p.c–National Film Board of Canada. visuals–Norman

McLaren, Evelyn Lambert. In color. sp. effects–Arnold Schieman.

m–Eldon Rathburn. performed by–The Buff Estes Group. 450 ft.

5 mins. (35 and 16mm.).

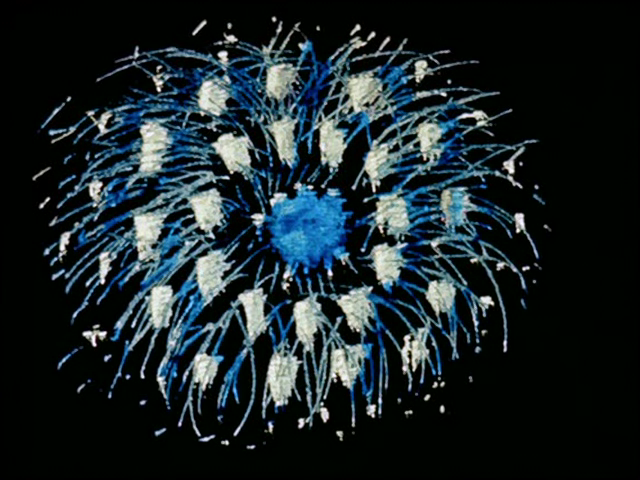

A characteristically bright, giggly and pithy animated short in

the McLaren manner, Short and Suite would probably be better still

if it had more inspired music to work with. Begone Dull Care (1948-

49), thanks to the ebullience and effervescence of Oscar Peterson’s

piano, was closer to a duel than a gloss on a ‘text’; this more modest

foray into synchronized, syncopated doodling plays with and against

a less improvised, less distinctive form of jazz, which is certainly

enhanced and highlighted by the visuals, but is not exactly transcended

by them. Beginning with pink and blue splotches to illustrate the bass

notes, and then clean white lines to match those played by the piano,

the design resolves itself into shifting parallel lines as the clarinet

comes in. Sometimes the lines wiggle or pulsate in strict

accordance with the music (one line reflecting the melody, the

other the rhythm), sometimes they curl into other shapes that

suggest the equivalent of a separate melodic line. Read more

From Oui (August 1974). — J.R.

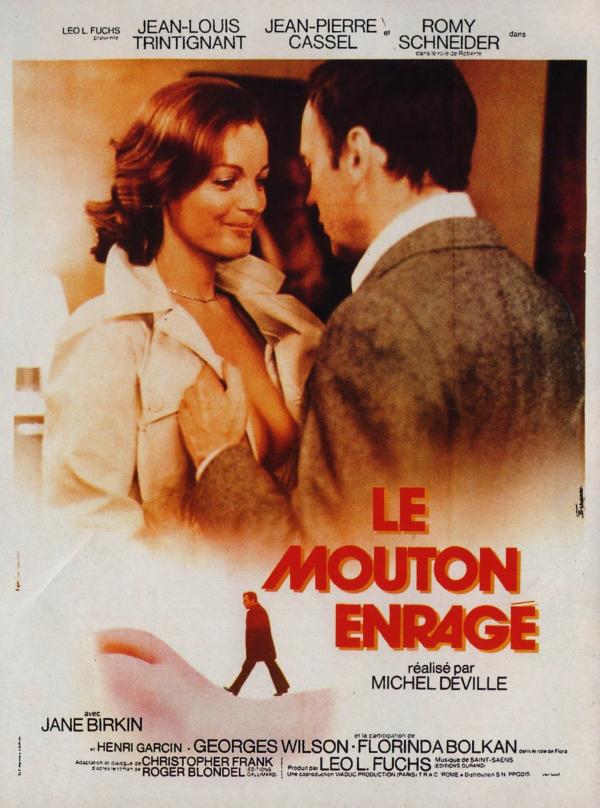

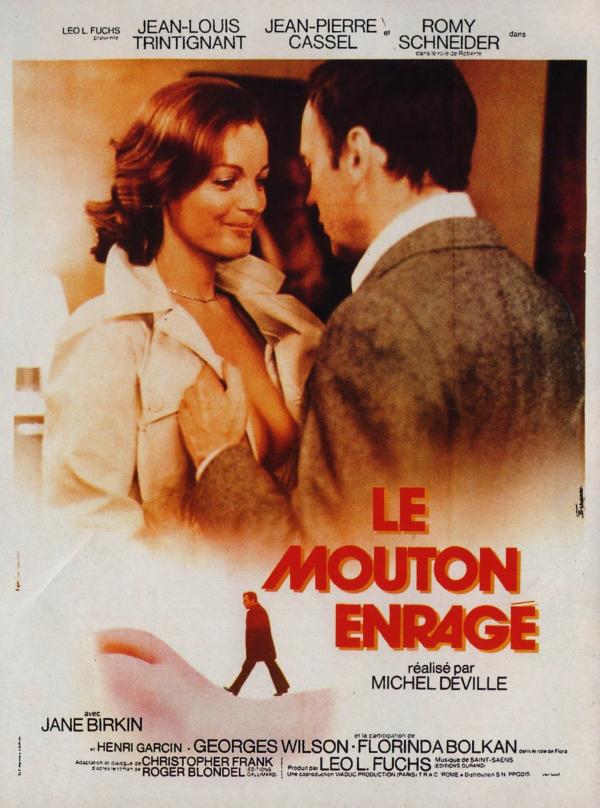

Le Mouton Enragé. Before the credits of Le Mouton Enragé come on, we see Jean-Louis Trintignant as Nicolas, an unassuming bank clerk who is so sheepish that he accepts a sandwich he hasn’t ordered in a café and winds up paying for a seat in a park where he doesn’t want to sit. Then he sees a pretty girl (Jane Birkin) standing alone by the Seine. A flush of courage overtakes him, he places a hand on her arm and says, “The person you’re waiting for doesn’t exist.” “Probably not,” she agrees, and voilà! The lamb is already on his way to becoming a lion. Carefully advised and tutured by his best friend (Jean-Pierre Cassel), Nicolas proceeds to make his way in the world; before the final reel, he has already become the editor of a jazzy tabloid and has bedded practically every attractive woman in the cast, including Birkin, Romy Schneider, Florinda Bolkan, and Estella Blain. The director of this graceful, inconsequential lark is Michel Deville, something of a specialist in neoclassy, softcore wish fulfillment — particularly harem fantasies where the ladies keep begging for more. (His Benjamin, a fleshy 18th century romp of a few years back, is a prime example.) Read more

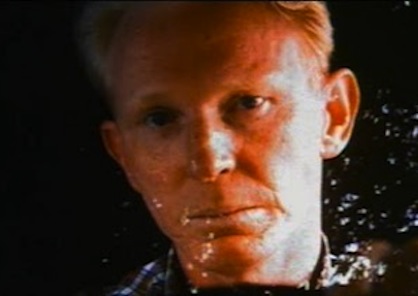

I believe this was commissioned by the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1993; my thanks to Adrian Martin for reminding me of its existence. — J.R.

Jon Jost’s three features starring Tom Blair display a surprising amount of consistency and continuity. Part of this undoubtedly stems from the singular power and intelligence of Blair — mainly known as a stage actor and director — who is officially credited for “additional dialogue” only in The Bed You Sleep In, but undoubtedly played a comparable role in earlier films. Another part just as surely comes from the way in which Blair’s particular talents have inspired and inflected some of Jost’s preoccupations. All three films focus on specific forms of all-American male dementia and violence, crumbling economies and communities and family units that come apart through contagious paranoid mistrust. And all three can be further read in part as corrosive, speculative self-portraits that reflect his changing position as a filmmaker. When he made Last Chants for a Slow Dance (Dead End) he was effectively without a fixed address himself and his searing look at the misogyny and wanderlust of Tom, driving around jobless and in flight from domesticity, is in part a dark reading of his own situation at the time. Read more