From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 492). -– J.R.

Italy, 1973

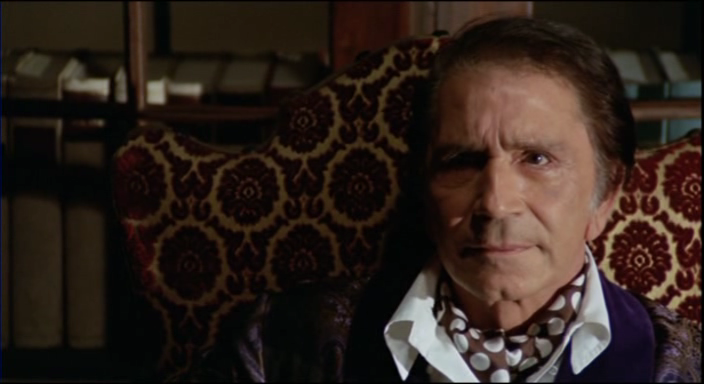

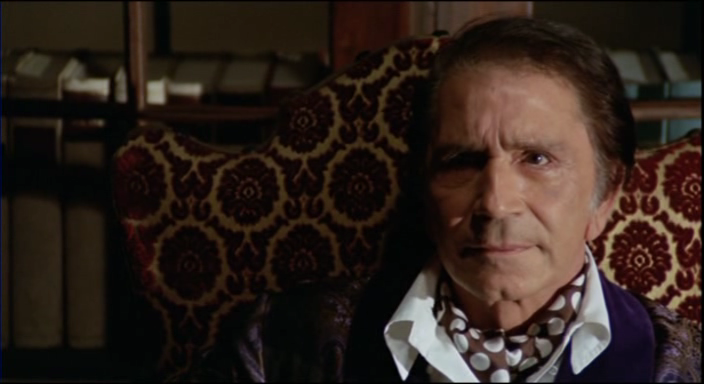

Director: Fernando Di Leo

Sicily. Under orders from Mafia chieftain Don Corrasco [Richard Conte], Nick Lanzetta [Henry Silva] sneaks into a projection booth to murder most of Cocchi’s gang of mobsters while they are watching a pornographic film. The next day, other members of the Cocchi gang kidnap Rina [Antonia Santilli], the teenage daughter of Daniello, a high-ranking member of the Corrasco clan, offering to spare her life in exchange for her father’s. Corrasco refuses to abide by this trade, despite Daniello’s willingness, and orders Lanzetta to kill him if he tries to negotiate a deal — an eventuality that shortly comes to pass. Police officer Torri, while investigating the screening room massacre, is severely chastised by his chief Questore for tapping the phones of the members of the rival clans. Meanwhile, Rina is enjoying her captivity — particularly sex with her captors, whom she takes on singly and in pairs. An informer tells Lanzetta the address of the hideaway, and after the former is murdered for spite, Lanzetta kills Rina’s captors and takes her to his own flat, where he is shocked to discover her unshaken by Daniello’s death and eager to seduce him. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, Vol. 43, No. 509, June 1976. — J.R.

Sonny Rollins

(Sonny Rollins Live at Laren)

Netherlands, 1973

Director: Frans Boelen

The essential value of this film made for Dutch TV — a non-nonsense recording of the Sonny Rollins Quintet performing four numbers at the “International Jazzfestival” at Laren in August 1973 — is the music itself, and the unusual courtesy with which it is treated by the film-makers. Apart from a few brief pans across enthusiastic members of the audience, all the action is centered on stage, and the various angles caught by the two cameramen — each of whom is occasionally glimpsed in footage shot by the other — are all admirably related to a direct appreciation of the music, with none of the attempts to pump up excitement artificially that infect most jazz films, from St. Louis Blues (1929) to Jammin’ the Blues (1944) to Jazz on a Summer’s Day (1959). Rollins, playing very close to the top of his form in recent years, begins “There Is No Greater Love” with one of his imaginative a capella intros before launching into the theme in medium tempo; serviceable solos follow from Matsuo [guitar], [Walter] Davis [Jr.] Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 2001). — J.R.

Bearing in mind Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, this astonishing 230-minute epic by Edward Yang (1991), set over one Taipei school year in the early 60s, would fully warrant the subtitle A Taiwanese Tragedy. A powerful statement from Yang’s generation about what it means to be Taiwanese, superior even to his recent masterpiece Yi Yi, it has a novelistic richness of character, setting, and milieu unmatched by any other 90s film (a richness only partially apparent in its three-hour version). What Yang does with objects — a flashlight, a radio, a tape recorder, a Japanese sword — resonates more deeply than what most directors do with characters, because along with an uncommon understanding of and sympathy for teenagers Yang has an exquisite eye for the troubled universe they inhabit. This is a film about alienated identities in a country undergoing a profound existential crisis — a Rebel Without a Cause with much of the same nocturnal lyricism and cosmic despair. Notwithstanding the masterpieces of Hou Hsiao-hsien, the Taiwanese new wave starts here. (JR)

Read more