Otto Preminger took LSD before making this demented, vulgar 1968 screwball musical about hippies taking over the world, in which his own trip is re-created as Jackie Gleason’s. This isn’t exactly funny, and it’s the last Preminger film one would pick to convince a skeptic of his talent, but it’s fascinating throughout. The satirical plot pits hippies against corporate gangsters lorded over by someone named God (Groucho Marx in his last film performance), whom Gleason used to work for. The cast mainly consists of aging TV stars (Gleason, Marx, Carol Channing, Frankie Avalon, Arnold Stang) and Hollywood has-beens (Peter Lawford, Burgess Meredith, George Raft, Cesar Romero, Mickey Rooney, Fred Clark). Preminger’s celebration of the counterculture may be peculiar (Channing serves as the major go-between and, oddly enough, the sanest character), but it’s certainly sincere. Don’t miss the hallucinatory Garbage Can Ballet — the apotheosis of this cheerful garbage can of a movie — and the sung credits at the end. 98 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the August 14, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

COLD HEAVEN

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

Written by Allan Scott

With Theresa Russell, Mark Harmon, James Russo, Talia Shire, Will Patton, Richard Bradford, and Julie Carmen.

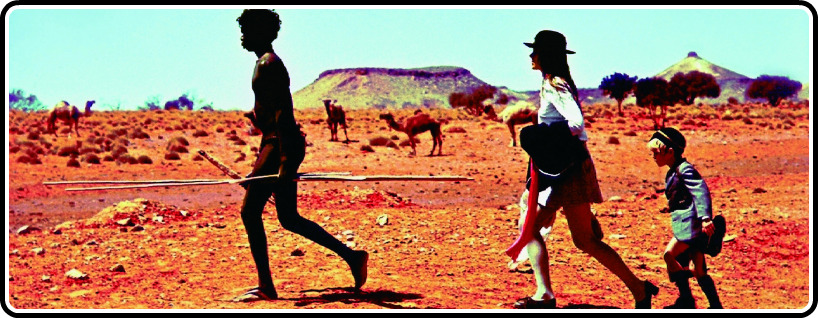

The sexy, volatile cinema of Nicolas Roeg might be said to operate under a kind of curse. Born in London in 1928, Roeg entered movies as a clapper boy at the age of 22 but didn’t become a cinematographer until his early 30s. After shooting such interesting films in the 60s as The Masque of the Red Death, Fahrenheit 451, and Petulia, he directed his powerful and still-dangerous Performance (in collaboration with Donald Cammell) in 1968, but then had to wait two years for Warner Brothers to release it.

After Roeg’s first solo directorial effort (Walkabout, 1971) came his first and only commercial hit (Don’t Look Now, 1973). He followed that up with two controversial cult items (The Man Who Fell to Earth, 1976, and Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession, 1979). In 1982 he made a feature (Eureka) that had a very limited release. Next in line was Insignificance (1985), then another feature with virtually no theatrical life in the United States (Castaway, 1986), then a third limited release (Track 29, 1988). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 2, 1997). — J.R.

Films by Rainer Werner Fassbinder

I’m still trying to figure out what I think of Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945-1982), the German whiz kid who’s the focus of a nearly complete retrospective showing at the Film Center, Facets Multimedia Center, and the Fine Arts over the next couple of months. An awesomely prolific filmmaker (he turned out seven features in 1970 alone), Fassbinder became the height of Euro-American fashion during the mid-70s, then went into nearly total eclipse after his death from a drug overdose — reminding us that the fate of a fashionable filmmaker is often to be discarded (as, more recently, have been David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino).

As skeptical as I often was in the 70s about Fassbinder as a role model, I’ve been more than a little disconcerted by the speed with which he’s vanished from mainstream consciousness. Having now seen two dozen of his 37 features, one of his four short films, and one of his four TV series — though I haven’t seen many of them since they came out — I find much of his work, for all its deliberate topicality, as fresh now as when it first appeared. Read more