This is a review of the John Waters original (1988) — not the Adam Shankman remake (2007) derived from the Broadway musical, which I haven’t seen. Thanks to the seeming omnipresence of the latter, I originally found it very difficult to find any stills from the former on the Internet. My review appeared in the March 4, 1988 issue of the Chicago Reader. Today I persist in thinking that America would be a better place if John Waters were hosting The Tonight Show. — J.R.

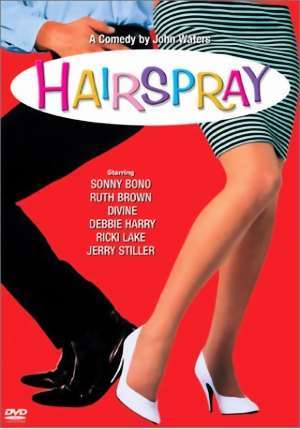

HAIRSPRAY

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by John Waters

With Ricki Lake, Divine, Leslie Ann Powers, Colleen Fitzpatrick, Ruth Brown, Sonny Bono, Debbie Harry, and Shawn Thompson.

As John Waters is the first to point out, Hairspray is “a satire of the two most dreaded film genres today — the ‘teen flick’ and the ‘message movie.'” But one of the nicest things about this exhilarating, good-natured pop comedy is that it actually is both a teen flick and a message movie. Satirical or not, it redeems as well as revitalizes both genres while celebrating their excesses.

This downscale, urban Dirty Dancing is a cunning crossover maneuver that opens as many doors to the mainstream audience as Waters can reach for, urging black and white, fat and skinny, blue collar and white collar, and generations some 25 years apart to join in the festive euphoria. The focus is The Corny Collins Show, a popular afternoon TV dance party in 1962 Baltimore, and everyone’s invited. Even the irreverence and shrill stridency that are part of the Waters mixture become subsumed under the arcane splendors of early-60s dance steps, glamorous teenage stars, and adolescent fantasies.

For people who have been following the offscreen career of Waters during the seven years that have passed since his last feature (Polyester), his triumphant entry into the big time should come as little surprise. His two wonderful books, Shock Value and Crackpot — works I can return to with more pleasure than is afforded by any of his previous films — reveal how deeply he is embedded in the knotty American grain: he is a good deal closer to Mark Twain, H.L. Mencken, Flannery O’Connor, and William S. Burroughs than he is to Salvador Dali, Jean Genet, Fernando Arrabal, or Alexandro Jodorowsky.

As an underground director, Waters was never more than an engaging amateur, a filmmaker whose reputation rested on the dogged literalism of his calculated outrages. The spectacle of Divine, a hefty drag queen, eating dog shit at the climax of Pink Flamingos — the moment that sealed Waters’s fame — was the sort of thing you only had to hear about in order to register or assess; seeing it added nothing to its significance, or lack thereof. Similarly, the overkill acting and gratuitous plot reversals were the recourse of an arriviste with practically no technique at his disposal and only his personality to sell; if the artlessness of a Warhol was relatively studied, Waters’s was definitely understudied.

If memory serves, when J. Hoberman and I began researching Waters for our book Midnight Movies in the early 80s, neither of us had ever seen a Waters film; for my own part, I had studiously avoided them throughout the 70s. As we buckled down to plow through most of the Waters oeuvre — Mondo Trasho (1969), The Diane Linkletter Story and Multiple Maniacs (1970), Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), and Desperate Living (1977) — it quickly became clear that however much an adolescent reading of Genet may have influenced the exalted scuzziness of Waters’s world (Divine’s name included), he was at the opposite end of the universe from Genet as far as style was concerned. Even at his best — in the demonic trajectory of Divine to her apotheosis in the electric chair in Female Trouble — he was more producer/entrepreneur than director/artist. The show really belonged to his star, and all he could give Divine was a story line and arias; stylish mise en scène wasn’t part of the package.

With the appearance of his first movie with a six-figure budget (Polyester) and his first book (Shock Value) in 1981, a different Waters began to emerge — more literary, humanist, and down to earth. The conceit in Polyester of a plush neighborhood drive-in featuring a Marguerite Duras triple bill was strictly a writer’s fancy, but not the kind that would have cropped up in any of his earlier films, where the gags were a good deal cruder. Domesticating Divine, planting her in the Baltimore suburbs, and matching her up with Tab Hunter represented another kind of adjustment, and the celebrations of Baltimore and trash culture in both his books cinched the bargain in establishing Waters as a dandy and an aesthete as well as something of an unpretentious cracker-barrel moralist, an Oscar Wilde of the American underbelly. Even while he continued to insist that he was apolitical, it was becoming clear that his nurturing of freakish societal rejects in his films — Divine, the late Edith Massey, Mink Stole, and others — was nothing if not a committed social act.

With the delightful Hairspray, Waters finally consolidates his position and winds up where he’s always really belonged: in the heart of the American mainstream, with a PG rating. As his seven years in the wilderness — chronicled in his recent collection of articles, Crackpot — makes clear, there was really nowhere else left for him to go. Studios were unwilling to finance either his film adaptation of A Confederacy of Dunces or his projected sequel to Pink Flamingos, which meant that he could neither step up nor slink back down the literary ladder he had constructed. All he could do was take a carefully aimed nosedive into the public swimming area below, and hope for a triumphant splash.

He’s made a perfect landing, for the irony is that Hairspray is every bit as personal a work as his sleaziest low-budget efforts. A few token gross-outs are sprinkled almost arbitrarily into the action to keep his older fans quiet — a popped pimple, a cavorting ghetto rat, and a smidgen of vomit — but his heart isn’t really in them, and if this film has the success it richly deserves, such obligatory signatures could be dropped from his next film without any real sense of loss. The people and the period flavor are what matter here, and Waters’s loving attention to both seems to be conducted without any hint of compromise, condescension, or loss of artistic identity. A graduation thesis in more ways than one, Hairspray proves that Waters can flourish as an artist without exploitation stunts or alibis.

Rivalry and spite are the two major forms of psychic fuel in a typical Waters plot. In Pink Flamingos, two families compete for the title of “The Filthiest People Alive.” In Polyester, after Divine catches her husband in a motel room with his secretary, he torments her by driving through their suburban neighborhood, declaring over a PA system his wife’s name, address, and weight and describing her alcoholism, gluttony, stretch marks, and hairiness, cackling maniacally all the while.

In Hairspray, the main rivalry is between Divine’s chubby daughter Tracy (Ricki Lake), the heroine, and trim villainess Amber (Colleen Fitzpatrick), who quickly loses her position and then her boyfriend Link to Tracy, the fat newcomer on The Corny Collins Show. The plot thickens considerably, making room for spite, when Tracy, Link, Tracy’s best friend Penny, and the latter’s black boyfriend Seaweed try to integrate the TV show, and the divisions become sharply political as well as personal. (In a dual role, Divine also plays Arvin Hodgepile, the racist owner of the TV station; Amber’s segregationist nouveau riche parents, played by Debbie Harry and Sonny Bono, are the show’s main sponsors — which makes the conflicts not only personal, racial, and familial, but also virtually tribal, with class playing a substantial role.)

Although Hairspray is as packed with hyperbolic detail as Waters’s previous movies, it differs markedly from them by being much more grounded in reality. One of the articles in Crackpot — written originally for Baltimore Magazine, and fairly bursting with civic pride — lovingly describes the real-life model for The Corny Collins Show: the top-rated Baltimore TV program, which thrived from 1957 to 1964, The Buddy Deane Show. It was hosted by a teenage Committee (called the Council in Hairspray), introduced a new dance step almost every week, launched a good many local teenage stars (including several girls with extreme bouffant hairdos), and eventually went off the air after the NAACP targeted the all-white show for protests. (There was a token all-black program once a month on the show — called “Negro Day” in the movie, a phrase that now drips with surreal period flavor — but no black Committee, and the protests called for integrating the show.)

Waters’s nostalgic and detailed appreciation for The Buddy Deane Show, enhanced by his cultivation of camp and outrage, gives Hairspray a heady exoticism that communicates as readily to teenagers today — judging from the audience I saw it with — as it does to members of Waters’s generation like myself. This is not merely a matter of period details such as clothes, hairstyles, and dance steps (including the Bug, the Dog, the Roach, the Limbo Rock, the Dirty Boogie, and countless others; the Madison started out in Baltimore, swept the country, and even made it across the Atlantic, where it can be seen, memorably, in Godard’s 1964 Band of Outsiders). In fact, the strange exuberance of teen culture in the early 60s is brought back even more by the sheer devotedness of Council members and fans to the show, and the pious gravity with which they discuss it. It’s no surprise that Waters is a lapsed Catholic: The Corny Collins Show, as he depicts it, has the luminosity and transcendent ritual power of an alternate church, and the rivalries and eventual political skirmishes are waged with all the fury of a religious war.

Even if Hairspray goads its auteur into becoming an up-front political filmmaker, this doesn’t prevent him from satirizing his own political positions at the same time. There’s a hilarious spouting of liberal clichés about race in a romantic make-out scene with the two lead couples outside a black dance hall, where the ghetto rat also puts in its appearance. (Elsewhere, though, at least a couple of civil rights slogans are employed anachronistically: King’s “I have a dream” and the widespread use of “We shall overcome” both surfaced after 1962.) And Waters is cautious enough not to follow through on the theme of interracial dating (Penny and Seaweed) when the film arrives at its slapstick finale.

But there’s no doubt about where his heart and allegiances lie, and in a way the film’s radical defense and celebration of fatness — capped by Tracy and her mother promoting a boutique called the Hefty Hideaway on the show in exchange for free wardrobes — is even more audacious than its attitudes about race. Jointly and separately, Ricki Lake and Divine are cordially invited to take the movie over, and they do so with glee and aplomb.