From the Chicago Reader, March 29, 1991. —J.R.

L’ATALANTE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Vigo

Written by Vigo, Albert Riera, and Jean Guinee

With Michel Simon, Dita Parlo, Jean Dasté, Gilles Margaritis, and Louis Lefevre.

“What was Vigo’s secret? Probably he lived more intensely than most of us. Filmmaking is awkward because of the disjointed nature of the work. You shoot five to fifteen seconds and then stop for an hour. On the film set there is seldom the opportunity for the concentrated intensity a writer like Henry Miller might have enjoyed at his desk. By the time he had written twenty pages, a kind of fever possessed him, carried him away; it could be tremendous, even sublime. Vigo seems to have worked continuously in this state of trance, without ever losing his clearheadedness.” — François Truffaut, 1970

L’Atalante is one of the supreme achievements in the history of cinema, and its recent restoration, playing this week at the Music Box, offers what is surely the best version any of us is ever likely to see. Yet the conditions that made this masterpiece possible were anything but auspicious.

When Jean Vigo started to work on his first and only feature in July 1933, he had no say over either the script or the two lead actors. It wasn’t that his producer was unsympathetic; on the contrary, Jacques-Louis Nounez had financed Vigo’s 44-minute Zéro de conduite — an anarchic, fanciful, and provocative depiction of a student uprising in a French boarding school — the previous year, and he hadn’t interfered with any of Vigo’s creative decisions. But Zéro de conduite had been banned in its entirety by France’s board of censors (it wouldn’t open in France for another 12 years), and in order to recoup some of his losses, Nounez felt that he had to exercise a few commercial restraints on this talented but volatile 28-year-old filmmaker — the son of an infamous slain anarchist — who had grown up hiding under assumed names.

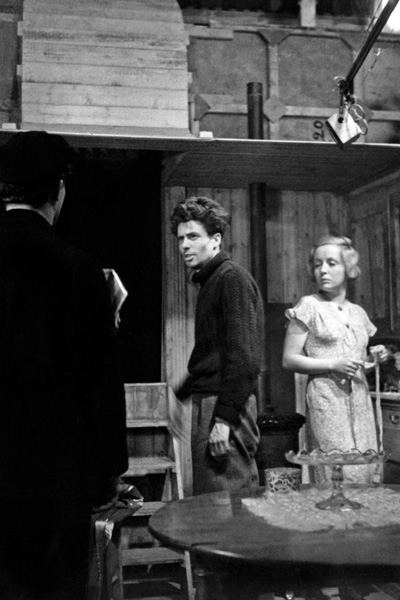

In fact, Nounez specifically requested that Vigo hold back on his usual impulses to experiment and make social statements and provided him with a highly conventional and unexceptional script called L’Atalante, authored by an obscure writer, R. de Guichen, who wrote under the pen name of Jean Guinée. It was a simple love story about a young barge skipper named Jean who marries a provincial woman named Juliette who’s never been to the city. Jean brings his bride on board the Atalante (the name of his barge), which is also occupied by an old sailor named Père Jules, a cabin boy, and a dog. The only conflict in the plot arises when Juliette meets a young sailor at one of the ports who offers to introduce her to the pleasures of the city. Jean manages to chase him away, but Juliette, still drawn to the city’s attractions, escapes anyway, and Jean, upset by her departure, refuses to go after her. Some time later, Père Jules defies Jean’s orders and goes out looking for Juliette, finds her, and brings her back. Life on the barge resumes, and Juliette becomes reconciled to her fate.

The popular French stage and movie actor Michel Simon, who had already appeared in four Jean Renoir films, was selected to play Père Jules, and the German film star Dita Parlo, who would subsequently play a lonely war widow in Renoir’s La grande illusion, was cast as Juliette; this package and the script were handed to Vigo, along with a request to include some songs in the film. Vigo — who was delighted with the choice of actors but much less happy with the story — agreed to these terms, requesting only a few minor changes in the script, such as the substitution of a peddler for the young sailor who tempts Juliette, the substitution of several cats for a single dog, and a somewhat more upbeat treatment of the ending.

To help him adapt the script, Vigo hired a friend who had been assistant director on Zéro de conduite, and he filled out the remainder of the cast with other friends, most of whom had acted in Zéro as well (Jean Dasté, whom he cast as Jean, had played the only sympathetic schoolteacher in the previous film). He also hired the same cinematographer (Boris Kaufman), composer (Maurice Jaubert), and lyricist (Charles Goldblatt) who had worked on Zéro. After several delays, shooting finally started in mid-November.

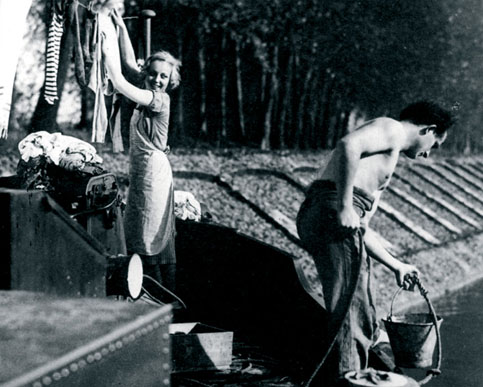

Vigo had been plagued all his life with weak lungs — a condition he shared with his wife, Lydou, whom he had met in a sanatorium when he was 23 — and had been feverish during much of the shooting of Zéro, his temperature ranging from 102 to 104. L’Atalante was shot on a barge from November to February (with periodic trips to the Gaumont studios, where sets were built duplicating some of the barge interiors and representing a working-class dance hall), and Vigo was sick roughly half the time. By the time the principal photography and rough cut (which proceeded simultaneously) were finished, he was too ill to work any further. After an abortive attempt at a holiday in the country he took to his bed, and during the seven remaining months of his life he went out only twice — once to view the work in progress with his editor, and once to see the virtually completed film with Nounez and his associates. (The film’s final aerial shot was filmed later according to Vigo’s instructions, so it’s likely that Vigo himself never saw it.)

Nounez was quite happy with the results, but his associates were not, demanding several cuts. Vigo reluctantly agreed to one major change — an extensive reduction of Père Jules’ search for Juliette in Le Havre — and the results were screened on April 25, 1934, for company representatives, exhibitors, and distributors. Most of them disliked the film, and Gaumont then decided to cut it much more drastically, rework the score in order to feature a current popular song (“Le chaland qui passe,” or “The Passing Barge”), and retitle the film after the song. At most, only two or three sequences in the film were left intact; this “final” version opened in mid-September at a single Paris theater and closed after a couple of weeks.

A few days after it closed, while Vigo lay dying, a street musician outside his apartment was playing “Le chaland qui passe” on an accordion, and Lydou, who had been cradling her husband in her arms, rushed to the window and tried to leap out. Some friends restrained her, and she was placed in a clinic in a state of delirium. (Vigo had jokingly described the strain of bacteria that caused his illness, streptococcus, as a little fat man in a top hat, and Lydou was asking to speak to the little fat man and demanding that L’Atalante be wrapped around the fat producers and set on fire. She died herself less than five years later; the eventual fate of her and Vigo’s daughter Luce, born in 1931, is apparently unrecorded.) [February 2010 postscript: In fact, Luce Vigo is alive, well, and active in France as a film critic.] [February 12, 2017: Luce Vigo, a Facebook friend to me and many others, coincidentally died the same day that this article was reposted.]

Attempts to restore Vigo’s original version of L’Atalante were made in 1940 and 1949, and those efforts produced the only versions of the film that have been visible until recently. (The first of these versions premiered in the U.S. in 1947 on a double bill with Zéro de conduite.) But in 1989, a few years after repurchasing all the surviving L’Atalante material in France, including some outtakes, Gaumont decided to do a more thorough job of restoration and located a nitrate version with the original title (but without the final shot or the excised material of Jules looking for Juliette) at the British Film Institute’s National Film Archives. What they aimed for was not a duplication of the version screened on April 25, 1934, but something much trickier — a restoration of Vigo’s original intentions based on his notes. Thus a series of short overlapping dissolves punctuating Père Jules’ comic demonstration of “Greco-Roman” wrestling, which were indicated in Vigo’s script but never executed, was brought about in the lab for the first time, and the placement of certain shots not indicated in the script was carried out by stray clues and guesswork; a few shots from previous restorations were also eliminated. [February 13, 2017: Bernard Eisenschitz is currently carrying out a new restoration, reportedly in order to correct the more fanciful changes in the previous restoration that is being considered here.]

Some of the decisions made are questionable — I’ll be getting to a couple of them later — but shouldn’t deter anyone from seeing this version, which runs for 89 minutes (the precise running time Vigo wanted) and contains about ten minutes of new footage. With the possible (and debatable) exception of a new print of Citizen Kane, which will be showing here in May, I doubt that a more beautiful film will be showing anywhere in Chicago this year.

Significantly, none of Vigo’s four films, including his shorts A propos de Nice (1929) and Taris (1931), survives in its original form today. But the fact that Vigo still remains one of the key figures in the history of cinema based on a total oeuvre that runs less than three hours gives some hint of how indestructible his talent remains and how trivial certain losses and alterations are in the broader scheme of things. Even though I’ve never seen the truncated and mutilated Le chaland qui passe that opened in 1934, I’ve little doubt that Vigo’s genius would be evident even there.

What does this genius consist of? It’s easier to define in Zéro de conduite, an exhilarating celebration of nonstop rebellion against bourgeois propriety and authority informed by free-flowing poetry and fantasy. But having recently seen that film and L’Atalante back to back, I’ve come to the conclusion that the much more “conventional” and commercial L’Atalante is an even greater work, for reasons that are less immediately obvious.

Terms like “surrealism” — or “realism,” for that matter — prove to be wholly inadequate in dealing with Vigo, despite the fact that he was a strong admirer of both Luis Buñuel’s surrealist Un chien andalou (“Beware of the dog — it bites,” he declared in a 1930 lecture) and the realist work of Erich von Stroheim. A first-degree reading of Zéro might conclude that it’s a surrealist film with realist touches, just as L’Atalante might initially appear to be a realist film with surrealist touches. But both descriptions fail because they imply a consistent surface speckled with “touches”; Vigo’s style and vision in both films are so seamless that the very notion of “touches” is inappropriate.

Zéro and L’Atalante both begin with shots of steam, vapor, and/or fog — a magical summoning of forces that is grounded in the real, which happens to be a train in Zéro, the barge in L’Atalante. (Boris Kaufman, who shot both films, later won an Oscar for his work on On the Waterfront, where he was still working wonders with ethereal textures; a key sequence in a park between Marlon Brando and Eva Marie Saint is virtually orchestrated by fog and the smoke from a burning trash can.) These openings make one think that from this point on anything can happen, but that the world it will happen in is still and always the world we know, however unexpected its form. In Zéro, the school principal may be a fastidious, bearded midget and the drawing on a schoolboy’s notebook may suddenly turn into an animated cartoon, but the characters and settings s/till belong to a recognizable and even familiar universe. This is not simply an ordinary place where strange things occasionally happen, but a poetic universe we all instinctively know.

In the supposedly more realistic universe of L’Atalante, the barge that travels up and down the river docking at real French towns and cities seemingly holds no cargo at all — save for one fleeting line in the dialogue (“Does unloading take long in a city?”), none is ever seen or mentioned — yet Jean clearly makes his living from some kind of cargo, and at one point even comes close to being fired in a company office in Le Havre, until Jules speaks on his behalf. In an ordinary film, this would be a lapse in credibility, but lapses are as foreign to Vigo’s mature filmmaking as touches, and the film’s cargoless barge, nevertheless brimming with both possibilities and actualities, is as real — or as unreal, for that matter — as any working boat in movies.

This sense of possibilities and actualities applies to many other aspects of L’Atalante as well. When I first saw the new version at the Toronto film festival last fall, I was struck by what seemed to be the film’s bisexuality — not a bisexual program of any sort, but a treatment of the characters’ sexuality that goes beyond the usual heterosexual norms and definitions. We know, for instance, that Jules has some sexual interest in women — we hear him allude a couple of times to someone named Dorothy, see him about to ravish a buxom fortune-teller, and clearly sense his attraction to Juliette as well — but this surely accounts for only part of his sexual nature. I was struck, for starters, by the highly charged ambiguity of his relationship to Juliette — a mysterious kinship that is implied in the similarity of their names — which comes to the fore whenever their responses to certain things suddenly coincide. One scene begins with him demonstrating his skill in using her sewing machine. She then gets him to model her skirt while she adjusts the hem (an experience that fills him with delight), and the sequence ends with them admiring one another’s hair and Juliette combing his hair after he has stripped off his shirt to show her his tattoos.

In another scene, in his cabin — where he introduces her to the exotic trinkets he has collected from all over the world on his sea travels –she comes upon a pair of human hands pickled in a jar. Jules indicates that they belonged to a friend who died three years ago (we see his photo) and that they’re all he has left of him — a piquant line that suggests that the friend may also have been a lover. (Just before this, to demonstrate the sharpness of his stiletto, Jules deliberately cuts his knuckle and then licks the wound — at which point Juliette instinctively licks her lips.) Jean suddenly enters, obviously upset by the intimacy he recognizes between Jules and his wife, and starts complaining about the cabin’s messiness and the smell of the cats; before he starts breaking dishes and a mirror in a rage, he asks Jules to identify a nude black woman in a photograph, and Jules cracks, “That’s me when I was young.”

In some ways, the behavior of the peddler (Gilles Margaritis) whom Jean and Juliette encounter in a cabaret is equally outrageous. “How nice of you to come,” he says to them when they arrive. “We were waiting for you to start the party. Bring on the biscuits, as dry as the duchess’s very dry pussy.” When he starts to flirt with Juliette in a song, he quickly interjects “You’re pretty, too” to Jean, and he wiggles his ass shamelessly when he’s dancing with Juliette a little later. (His marvelous sales patter, which mainly takes the form of a musical number, also implies a certain link between Juliette’s libido and consumerism that is played out elsewhere in the film.)

There’s certainly no question that the sensuality of Vigo’s work as a whole — and especially the carnal impact of flesh touching flesh — has a special aura and potency. The key moment that kicks off the schoolboys’ full-scale revolt in Zéro de conduite is a fat chemistry teacher stroking the hand of an effeminate, long-haired boy named Tabard — the character in the film who, it is said, most represents Vigo, and who responds by screaming at the teacher, “I say shit on you!” (Vigo’s Catalonian father — a controversial anarchist and newspaper editor who was strangled in his prison cell by unknown parties when Vigo was 12 — had composed a headline for his socialist paper which said exactly the same thing, addressed to the government, in large letters. And at the age of 17, following his first arrest, Vigo’s father changed his name, as an act of defiance, to Miguel Almereyda, the last name a deliberate anagram for a phrase that translates roughly as “There is shit.”)

Vigo’s biographer, the Brazilian film archivist P.E. Salles Gomes, provides us with one intriguing anecdote that relates to Vigo’s attitudes about sexuality. Just after the end of shooting, when Vigo and his actor Jean Dasté were invited to lunch by Margaritis, they arrived arm in arm, both whimsically dressed, according to Margaritis’ mother, who was cooking the lunch, “in women’s summer frocks, with bare arms and legs, wearing small hats on their heads, one of them apparently in an advanced state of pregnancy.”

This carnivalesque gesture seems wholly compatible with Vigo’s universe and vision, but whether it pointed to any active bisexuality on Vigo’s part is ultimately irrelevant. Just as L’Atalante winds up making terms like “realism” and “surrealism” seem inadequate, it also makes terms like “heterosexual,” “homosexual,” and even “bisexual” seem beside the point. Vigo’s grasp of the world is a particular kind of alertness and aliveness that confounds most social and aesthetic categories because it has the freedom to call upon anything and everything that might enhance our appreciation and understanding of what he has to show, ordinary distinctions be damned.

At one point, we’re told by P.E. Salles Gomes, when Vigo was scouring Parisian flea markets to fill Jules’ cabin with exotic trinkets — he also called on friends to contribute several objects, and even stole some wrought-iron wreaths from the Montparnasse cemetery — he was especially interested in finding one of Alexander Calder’s mobiles. The usually astute Salles Gomes concludes that Vigo “must have eventually realized that, although they were not well known in 1933, the presence of a mobile among an old sailor’s mementos would have been out of place.” On the contrary, I think we have to argue that in a Vigo film — most of all, in this Vigo film — a Calder mobile would not have been out of place, not even in an old sailor’s junk-strewn cabin. The mystical point at which imagination and observation fuse is present in L’Atalante in virtually every shot.

Even without the Calder mobile, many of the shots in the film are simple awestruck discoveries, and the sequences that coagulate around them are often ones that simply arose from these discoveries. Consider the numerous cats of Père Jules’ that roam about the barge, affecting the events of the film in numerous ways. We know that they have an autobiographical basis (Almereyda was a fanatical cat lover, and the single-room attic apartment in which Vigo was born was filled with scrawny alley cats), and the poetic mileage the film derives from them goes well beyond their function as suggestive décor. One of them scratches Jean’s cheek when he first steps aboard after the wedding, and soon afterward Jean is furious when a litter of kittens is born in his and Juliette’s bed — two signals at the outset that Jules and what he represents threaten the sexual health and privacy of the couple, even if it’s Jules who ultimately succeeds in reuniting them at the end.

During a pivotal and wonderful sequence in which Jules magically succeeds in repairing an old gramophone, there’s a brief shot showing kittens crowded around the machine as if they’re listening intently to the record playing, one of them standing inside the shell-like loudspeaker. The gramophone and its repair originally served a minor and quite different role in the scene, but when the kittens unexpectedly became fascinated with the machine between takes, Vigo quickly filmed them that way and then reworked the entire sequence around this improvised shot — turning these kittens into a kind of Greek chorus in the process.

During the same sequence, there’s a somewhat jarring cut from Jules, the cabin boy, and Jean (brooding over Juliette’s absence) on deck to Jean rubbing his cheek against and licking a large block of ice on land. The logical place for this startling and moving shot is a little bit later, after Jean has docked the barge at Le Havre and is looking for Juliette on land; according to Variety, the restorers placed it where they did solely on the basis of how certain individual shots were numbered.

My only other major objection to their work (which involved about 40 editorial changes in sound and/or image from previous versions) is their artificial prolongation of the final shot, through a technique called step-printing, in order to make Jaubert’s score conclude at precisely the same instant that the shot does — a kind of symmetrical neatness that seems counter to Vigo’s own looser sense of balance and closure. Letting the music run past the shot, as it did quite pleasurably and naturally in the earlier versions, would surely have done his memory no disservice. (Gracefully sculpted around the action throughout, Jaubert’s wonderful score also plays off certain natural sounds — using the barge’s engine as a metronome, much as he used a train engine at the beginning of Zéro.)

I can’t hope to do more here than hint at a few of the riches in L’Atalante, including the lasting impact it has had on subsequent generations of filmmakers. (There’s an extended hommage in Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris, for instance; and I think it could be argued that practically all of the good things in Truffaut’s work — most of them realized most fully in his early features — would have been inconceivable without Vigo’s direct influence.) In conclusion, then, let me focus briefly on three aspects of the film that deserve more detailed consideration than I can give them here:

(1) Michel Simon as Père Jules offers what is just about the most wondrous character acting I know of in movies; but even this performance would be substantially less than it is if it weren’t for Vigo’s superb sense of how to integrate him with everything else in the picture. At once the film’s only pure infant and its only pure adult, he embodies a kind of stream-of-consciousness, polymorphous-perverse behavior that perfectly exemplifies the film’s capacity to integrate fantasy and reality. His two extended scenes with Juliette in the barge’s lower cabins are perhaps the richest examples of this — delirious, free-form two-part inventions whose pivots are either props or phrases by Juliette that send him off into fresh paroxysms of play or demonstration.

The only remote equivalents to Simon’s character in the American cinema are the crotchety comic parts played by Walter Brennan in Howard Hawks’s To Have and Have Not (a rummy named Eddie) and Rio Bravo (a cripple named Stumpy), both of whom play a major role in defining (not to mention cussing out and irritating) and ultimately uniting the other characters. But Brennan never quite transcends his function as comic relief, while Jules is much more central. James Agee compared him to Caliban, but in other respects he is even worthy of Falstaff.

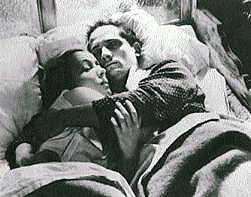

(2) Conceivably the most erotic sequence in the movie is one that poetically and rhythmically intercuts between Jean and Juliette, each of them in separate beds many miles apart, suffering from insomnia and longing for each other. Another powerful two-part invention, as symmetrical as Vigo ever gets, it rhymes Juliette and Jean fondling their own torsos and musically plays with their restless movements in and out of the frame; both characters are speckled mysteriously with polka-dot shadows, implying a common ground to their individual torments and desires — a mutual passion that makes their subsequent reunion as exciting and fully satisfying as any last-minute Hollywood clincher.

(3) Apart from its loose narrative construction, L’Atalante is far from being an art movie in any ordinary sense. If it follows the conventions of any genre, it comes much closer to being a musical at several critical junctures — including the climactic moment when Jules finds Juliette in a record parlor, listening to the sailor’s song that serves as one of the score’s major themes. Just as the movie confounds our usual understandings of realism and surrealism, documentary and fantasy, and sexuality with its various prefixes, it also collapses what we ordinarily mean by “commercial” and “popular” on the one hand, “arty” and “experimental” on the other. What category can we hope to assign a movie whose beauty and greatness finally rest on the simple gratitude it makes us feel for being alive?