This book review, which I’ve alluded to previously on this site, appeared in the November 2, 1980 issue of The Soho News. —J.R.

Under the Sign of Sontag

Under the Sign of Saturn

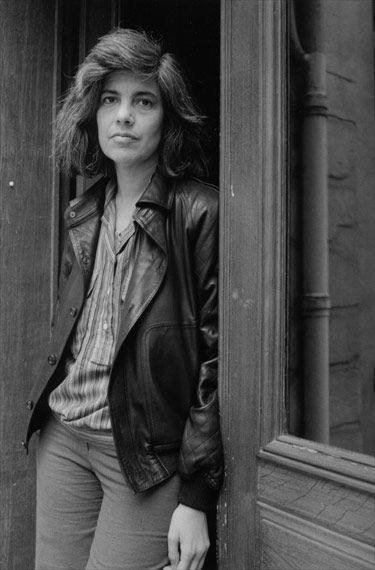

By Susan Sontag

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $10.95

If, dialectically speaking, every book can be said to have an unconscious — a repressed subtext — one can find glimpses of the unconscious of this one in the misleading flap copy that quotes from an interview (“Women, the Arts, and the Politics of Culture,” Salmagundi 31-32) and mentions the inclusion of a “famous exchange on fascism and feminism” (apparently with Adrienne Rich, in the March 20, 1975 New York Review of Books), both regrettably missing from this slim volume of seven essays.

These omissions betray the absence of a gritty, indecorous social context — a sense of Sontag existing in the world, not merely staging grand Platonic shadow-plays in the theater of her mind. Much as Illness as Metaphor (1978) was partially structured around her refusal to allude once to her own personal struggle, this book discreetly, indirectly dances around the notion that the subject of every essay proposes a different kind of mirror to the author, a speculative self-portrait.

Against Interpretation (1966) is one of the best popular guidebooks ever written to mid-century modernist taste and its diverse encounters with the sexuality of thought. Styles of Radical Will (1969) is a series of variable skirmishes on some of the exciting, if treacherous, battlefields of the late ’60s. Speaking as someone who used the parenthetical examples of these essays rather like the way an earlier generation used Eliot’s footnotes to The Waste Land — as a central tool in my liberal arts education — I am disappointed in not being able to appropriate Sontag’s recent, more inner-directed essays in quite the same fashion. As an old college friend observed recently, “She doesn’t belong to us anymore.”

Let’s put it differently: the pieces here are all precisely dated — from 1972 to 1980 — without being existentially placed. Like Goethe or Thomas Mann (both frequent reference points), they speak to us from some remote Mount Olympus of the imagination, an exclusive key club whose members are either male misogynist bookworms (Roland Barthes, Elias Canetti, Paul Goodman) or at least their kindred spirits (Antonin Artaud, Walter Benjamin, Hans-Jürgen Syberberg) — doleful, solitary visionaries shoring their heroic ruins against the fragments of a discontinuous culture.

***

The essays in this collection become more interesting when one examines them in pairs or in threesomes, where the ideas and inflections gain in depth by being carried through different settings. One should shake up their chronological order and view them in other groupings: very personal obituaries of Goodman and Barthes; Artaud, Benjamin, and Canetti — an ABC of lonely, eccentric accomplishment — examined for the climates of their temperaments and the shapes of their careers.

A largely unconvincing panegyric to Syberberg’s interesting Hitler, a Film from Germany is complemented by essays located to the left and right of its arguments. On the left is “Fascinating Fascism,” a bracing attack on formalist defenses of Leni Riefenstahl and some troubled reflections on the erotic currency of Nazi symbolism — the only genuinely political and socially engaged article in the book. On the right is “Mind as Passion,” the closing essay, which argues that “Canetti’s thought is conservative in the most literal sense. It — he — does not want to die….Recurrent images of needing to feel everything inside himself, of unifying everything in one head, illustrate Canetti’s attempts through magical thinking and moral clamorousness to ‘refute’ death.”

Both these forays help to explain, in their different ways, how and why the Black Maria (Edison’s first film studio) of Hitler, which stirs Sontag’s and Syberberg’s imaginations to such hyperbolic flights, resembles the inside of a tomb –catalogued and inventoried at lyrical lengths in the final pages of her novel Death Kit. “The enterprise that one takes through a Surrealist landscape,” she writes of Hitler, “is always quixotic — hopeless, obsessional; and, finally, self-regarding.”

The same could be said of this peculiarly airless appreciation, which stops just short of defining a masterpiece as a work that reflects and restages Sontagian preoccupations rather than expanding or elucidating them. Somewhere along the line the radical modernist has turned into the decadent classicist.

The problem is that Hitler is removed “through magical thinking” from any social history or space of its own. “Taste is context, and the context has changed,” Sontag writes earlier of fascist art. But what about the contexts of Hitler — shown in German classrooms, as a weekly serial on BBC, or presented by Francis Coppola in Lincoln Center with a different title (Our Hitler) at $12 a head — that help to determine its own social meanings and about which Sontag remains resolutely silent? (By furnishing a quote to Coppola’s ads for the latter event — “One of the great works of art of the 20th century” — she certainly chose to contribute to that context.)

***

Other objections to this essay are more a matter of style and rhetoric. It’s disconcerting to read, “A posthumous event, in the era of cinema’s unprecedented mediocrity,” on page 140 and then, on 163, “In the era of cinema’s unprecedented mediocrity, his masterpiece has something of the character of a posthumous event.” When we’re told that unlike Ivan the Terrible and 2001 (among other “mega-films”), Hitler is “open to personal references as well as public ones,” it’s hard to believe that viewer as sophisticated as Sontag could fail to see the personal references in the Eisenstein and Kubrick films. Is she merely not listening to herself, lulled by the sound of her own voice?

It is often, to be sure, a melodious, mellifluous voice, even in its bittersweet, half-defeated ironies, ambivalences, and love-hatreds (that animate so much of On Photography), or in its odd tics, like a determination to drag surrealism in at every juncture of this book, to explain anything, everything. A fondly remembered writerly voice whose delicate, desperate clarity still sometimes shines through the stardust tarnish that diffuses so much light.

Why, in the Barthes obit, does she fail to mention that great writer’s happiest, most ecstatic books, The Pleasure of the Text and the still untranslated meditation on “Japan,” L’Empire des signes? Perhaps because, as Sontag herself usefully pointed out in the Salmagundi interview, her 1964 “Notes on Camp” was merely a second attempt to name a sensibility, after trying to accomplish the same thing with morbidity and death — a subject that eventually swamped her. It swamps too much of the present, saturnine collection.

—The Soho News, November 12, 1980