From the Chicago Reader (November 28, 2003). — J.R.

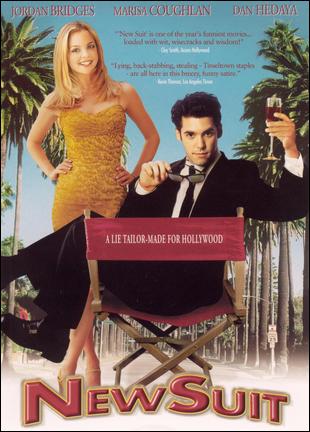

New Suit

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Francois Velle

Written by Craig Sherman

With Jordan Bridges, Marisa Coughlan, Heather Donahue, Dan Hedaya, Mark Setlock, Benito Martinez, Charles Rocket, and Paul McCrane.

As the opening narration makes clear, New Suit — a satirical comedy about Hollywood suits — is loosely based on “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Kevin Taylor, a 24-year-old script editor and frustrated screenwriter, is already jaded after 18 months working in the office of has-been producer Muster Hansau. Taylor (Jordan Bridges) gets especially irritated one day after hearing some of his hotshot coworkers spout bullshit at the studio commissary. He gets up from the table and buys a strawberry ice cream cone from a guy named Jordan, then returns and starts talking about an imaginary hot new script called “New Suit” by an imaginary writer named Jordan Strawberry that he says his bosses are excitedly pursuing.

His tablemates simultaneously claim they’ve already heard about the script and pump him for more information. Before long the whole town is talking about this promising property — especially after Kevin’s former girlfriend Marianne, a rising agent, overhears him saying that Strawberry is “unrepresented.” She promptly claims to be representing him, which starts a bidding war between two studios.

It’s an obvious premise, but I was pleasantly surprised to discover that Francois Velle directs this farce without any of the glibness that scriptwriter Craig Sherman is attacking. The characters are all recognizable studio types, and some of them are quite funny. Paul McCrane is especially good at underplaying an uptight studio chief whose name, Braggy Shoot, seems to invite overkill, and Heather Donahue, as one of Hansau’s assistants, has a touching scene in which she responds to one of her boss’s tirades by collapsing in front of a refrigerator and devouring someone else’s sandwich. As Dave Kehr points out in the New York Times, Velle also manages to soften the implied harshness of Sherman’s script by making the characters enjoyable in their own right, independent of the plot: “Though the script gives us every reason to believe that Kevin despises Marianne, the two are shown forming a jolly, piratical friendship as they plan to defraud and humiliate the abusive Hansau.” More generally, the story is compelling not because it’s believable in any literal sense, but because it delivers a general truth about Hollywood and about this country.

If Sherman and Velle were really interested in giving us a detailed picture of how hot air propels the studios, they might have come up with something closer to Sammy Glick’s modus operandi in Budd Schulberg’s 1941 novel What Makes Sammy Run? — still probably the best novel about the way Hollywood works. Glick uses a ruse at the studio commissary that’s similar to Kevin’s, but he’s not trying to demonstrate any philosophical or sociological point. He tosses out a few details about a nonexistent screenplay, figuring that by the time the rumors make their way back to him his sketchy ideas will have been so embroidered he won’t have to do much of the hard work of invention.

Schulberg was more interested in how pictures got made than in how deals got brokered. But if a picture named “New Suit” gets made in this movie we never find out — and it doesn’t matter much. The biggest difference between Schulberg’s story and Sherman’s isn’t just that in 60 years Hollywood has shifted from a producer’s playground to an agent’s business. It’s that New Suit is most interesting not for its literal story but for its subtext — namely the way that energy and emotion can become centered on a void.

The main explanation for this phenomenon in this movie is fear and conformity, which sounds reasonable enough. But the movie’s also hinting at other motives. The climactic bidding war between rival producers who used to work together is clearly driven by macho competitiveness, which isn’t very interesting in itself. Far more interesting is the reaction to the hero’s revelation that the property that’s been bought for a huge sum doesn’t exist: with just a modicum of effort, Marianne spins this into the revelation that Jordan Strawberry is actually Kevin Taylor, eliciting a round of applause and raised champagne glasses for all concerned. It seems the real issue for all of the characters except Kevin isn’t whether a particular script exists, but whether their lives have purpose. And if a nonexistent script can make all these characters feel a sense of purpose, that’s just fine.

In short, what seems to drive these people is a kind of transcendentalism — all the chips at stake are ultimately symbolic and therefore of value only for what they represent. This attitude, and its concomitant faith and gullibility, has many comic implications. It’s also a reflection of absurdities in the world around us, such as the statement made last July by Arthur Sulzberger Jr., publisher of the New York Times, to his employees after the departure of Jayson Blair led two senior editors to resign: “There’s no complacency here — never has been, never will be.” And it points to a national trait described by Mary McCarthy in a 1947 essay, “America the Beautiful”: “The buying impulse, in its original force and purity, was not nearly so crass…or so meanly acquisitive as many radical critics suppose. The purchase of a bathtub was the exercise of a spiritual right. The immigrant or the poor native American bought a bathtub, not because he wanted to take a bath, but because he wanted to be in a position to do so. This remains true in many fields today; possessions, when they are desired, are not wanted for their own sakes but as tokens of an ideal state of freedom, fraternity, and franchise. ‘Keeping up with the Joneses’ is a vulgarization of Jefferson’s concept, but it too is a declaration of the rights of man, and decidedly unfeasible and visionary. Where for a European, a fact is a fact, for us Americans, the real, if it is relevant at all, is simply symbolic appearance. We are a nation of twenty million bathrooms, with a humanist in every tub.”

That’s a cheering thought, and it helps explain why New Suit, for all the anger behind it, is mainly a cheerful film, taking more pleasure than pain in its observation of something approaching madness. This doesn’t mean that all the implications of that observation are pleasant. I was reminded of George Packer’s “Letter From Baghdad” in the November 24 issue of the New Yorker, in which he describes the Bush administration’s assumptions about the governing of Iraq after the invasion as “so wishful” they “bordered on self-deception” and in which he quotes an anonymous senior official’s explanation: “‘It isn’t pragmatism, it isn’t Realpolitik, it isn’t conservatism, it isn’t liberalism,’ the official said. ‘It’s theology.'”