The following article was written for the June 8, 2001 issue of the Chicago Reader, to coincide with the release of Jafar Panahi’s The Circle in Chicago — although a differently edited version was published. This is my original version, which I included in Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia, a 2003 collection I coedited with Adrian Martin. (Lamentably but unsurprisingly, this was the only section of the book that was left out of the Persian translation.)

One indication of Panahi’s extraordinary courage, after his appalling incarceration in Tehran’s Evin prison back in March, was the fact that he expressly requested not to be accorded “special” treatment because of his status as an artist and filmmaker. It seemed worth reposting this article on December 21, 2010, not only because of the shocking sentence received by Panahi after his trial, but also to correct the original misdating of this article on this site and in Movie Murtations, which I learned about via David Bordwell’s site. — J.R.

Squaring The Circle

Last month, I was taken aback by an email from a colleague — not a cranky stranger — waiting for me at my office computer one morning. It said, “I thought, as an apparent defender of the Islamic Republic of Iran, that you should read this.” Before I even accessed the link — an AP story about a woman stoned to death by court order for appearing in porn movies — I wrote him back that I felt insulted by the implication that regarding Iranians as human beings meant supporting a totalitarian regime. He promptly sent back an apology, but added, “It’s just that sometimes it sounds as if you regard their regime as `better’ than ours. Perhaps I’m misreading you.”

One might ask, “better” for whom? And why put quotation marks around that word but not around “their” or “ours”? But I’m getting ahead of myself. To tell the truth, his second email upset me even more than the first, and not only because it was a misreading. If the first email could be rationalized as a sick joke — a bit like being called a “nigger lover” when I was an Alabama teenager (an epithet sometimes followed by, “Just kidding!”) — the personal pronouns in the second chilled my blood, carrying me back to the either/or, us/them mentality that is surely the most primitive as well as the most dangerous of all our Cold War legacies. It scares me even more when I reflect on where this country’s current isolationism may be leading us, and what those pronouns may wind up doing to live bodies as well as developing minds.

I guess this must sound like an excessive response. But I have to admit that those words and what they suggested haunted me for the rest of the week. They echoed in my ears like a tribal directive, implicitly telling me that my colleague and I — along with Timothy McVeigh, Janet Reno, Jeffrey Dahmer, and every other American who might be construed a mass murderer — shared something irreducible in terms of our identities that couldn’t be superseded by anything I had or felt I had in common with anyone else in the world. They were implying that even though I had no choice about being born an American, a white male, a Jew, or a southerner, these were none the less the very attributes that entitled me to use the personal pronouns “my” and “our” — unlike the more existential attributes I chose for myself, such as remaining an American but not a southerner, remaining a Jew but not a practicing one, or, most importantly, regarding myself as a member of the planet. Like it or not, we — my colleague, I, and those others mentioned — were all members of the same club, and other folks need not apply.

But what did my colleague actually mean by “their” regime, anyway? Could it honestly be called a regime belonging to the woman who got stoned to death? If it was, how could one account for her appearing in porn films, which isn’t “their” sort of thing at all? Even the Iranians I know in Iran are people I wouldn’t dream of insulting by identifying them with the oppression they all have to cope with, just as I’d feel slimed if someone insinuated that George W. Bush was “my” personal leader. That twerp, whom I and most of my fellow citizens didn’t even vote for? After all, it’s him and his sponsors, not “us”, who are breaking all those international treaties and polluting our planet for coin — or would it be more appropriate at this point to call it “their” planet? One reason, in fact, why I like remaining an American is that there aren’t so many laws here obliging me to take the blame or the credit for someone like Bush.

The only time I’ve been in Iran — last February, to serve on a film festival jury — I was treated with a great deal of warmth and hospitality by people I didn’t regard as totalitarian, maybe because Iran and Islam are far from the same thing. But my hosts and I were still subject to totalitarian laws, this being a country where, for instance, it’s illegal for men and women who are unmarried to touch one another in public, even to shake hands. This doesn’t mean they don’t touch one another in private; the parties I attended in people’s homes were pretty relaxed. But it does mean that I can’t tell you everything I saw and heard in Iran without getting some friends into trouble — and I can’t even say this much without giving a false impression that I’m lewdly winking about something. One of the big problems with totalitarian societies is how cramped they make everyone’s communication in general — tribal personal pronouns and Cold War paranoia included. During the single afternoon I spent in East Berlin before the wall came down, the most disturbing aspect of the bars and cafés I visited was how deadly quiet they all were, with voices seldom rising much above whispers.

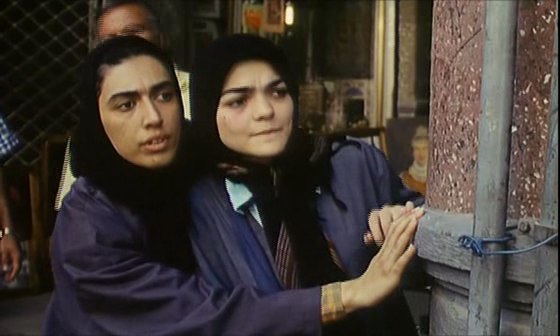

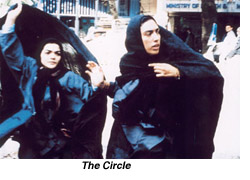

This wasn’t the case in the Iranian cafés and restaurants I visited (there are no Iranian bars). But one does worry at times in public places about being observed, and filmmaker Béla Tarr, a fellow juror in Tehran, told me that the city reminded him of his childhood in Budapest. It’s part of the singularity of Jafar Panahi’s The Circle — and indicative of the courage and perceptiveness of the man who made it — that this is almost certainly the first Iranian movie that depicts this everyday fear and makes it part of an overall emotional texture. It’s a far cry as well as a quantum leap from The White Balloon and The Mirror — Panahi’s previous two features, both of them relatively lighthearted films about little girls — though it also makes me want to see those pictures again, because it clearly has certain stylistic as well as thematic links with them. All three features, for starters, present unaccompanied females on the streets of Tehran and play with notions of real time. But it’s with The Circle, in any case, that Panahi fully establishes his credentials as a master, a man who clearly knows filmmaking like the back of his hand.

***

Perhaps the most talented of all of Kiarostami’s disciples — he worked as an assistant on Through the Olive Trees and got Kiarostami to write the story of The White Balloon — Panahi can be credited with going well beyond his mentor in at least one major respect: by giving a particular political thrust to the same kind of narrative ellipsis and deliberate formal construction that Kiarostami is famous for. Showing how formal and political radicalism can work together is itself a sizable achievement given the way such projects are commonly viewed as being at loggerheads with one another, especially in this country.

As one example of what I mean, some of the central women characters in the film are fresh out of prison, but we never find out why any of them went to jail in the first place, and our understanding in some cases of whether they escaped, got out on parole, or simply reached the end of their sentences is either delayed or remains incomplete. We gradually come to realize that none of this information matters, given the story that Panahi has to tell, and that our lack of certainty about these details even adds a particular edge to the viewer’s engagement with the storytelling.

It’s an edge that qualifies as an ideological inflection once we realize that this is a movie that refuses to allow us to rationalize the way these women are treated by their society with any excuses or alibis. The film lacks villains or heroes in the ordinary sense, because the protagonists all have their lifelike mixtures of strengths and weaknesses. But it’s obvious from the beginning that what these women have to put up with is intolerable, and Panahi refuses to allow us to say at any point, for any reason, that any of them is “getting what she deserves”. As with Kiarostami, the narrative gaps constitute a form of respect for the viewer, but in this case the respect is not merely for the audience’s imagination but also for its ethics, its innate sense of decency. It’s a sensitivity we wind up sharing with Panahi and therefore feel entitled to call “ours” — meaning, in this case, his and ours, not “ours” in contradistinction to “that Iranian’s”.

The point at which The Circle really kicks in for me is when a teenage character named Nargess keeps trying and failing to board a bus that would take her back to Raziliq, her home town. We know she wants desperately to go, but something keeps preventing her. Panahi and Nargess Mamizadeh, the wonderfully expressive and spontaneous nonprofessional playing the part, create a virtual symphony out of all the things we know and don’t know about her, adroitly dovetailed with all the things she knows and doesn’t know as well as the schedules of the various buses leaving. Like the wedding party that keeps re-entering the movie at separate stages, her character is both consistent and unpredictable, and her disorientation in the terminal as she wanders about soon becomes ours. She sports a large bruise under her right eye, and we never learn its source; she’s convinced that a reproduction of a Van Gogh landscape that she sees on the street depicts her home town, though the painter forgot to include certain details. We also suspect but can’t confirm that her older pal Arezou (Maryiam Parvin Almani), whose name means “hope,” turned a trick in order to raise money for her bus fare, and we aren’t told why Arezou eventually decides not to go with her either. What we gradually discover is that Nargess’s failure to board may be a phobic reaction, and assuming that we ever learn its cause, it may not be until very late in the picture — when we see another woman boarding a police van — that we can figure out its source.

In fact, it’s part of the overall risky strategy of this poetically interactive movie to have the story of one woman continued or “completed” by the story of another — a highly artificial procedure that the film miraculously brings off by making all the fragments we glimpse both extremely lifelike and congruent with one another. This method may constitute a kind of shotgun wedding between formalism and realism, poetry and agitprop, but Panahi stages the match with such natural grace that it sometimes feels like a marriage made in heaven.

This is the first Iranian noir I’ve seen — and I’m using “noir” here to denote a style that isn’t “ours” but the world’s. After all, the term itself is French, and it’s worth adding that France has probably influenced Iran as much as us. (The most common way of saying “thank you” in Tehran, audible in The Circle, is “merci”.) Fear and noir typically go together — and the most frightening of Val Lewton’s noirish B films, The Leopard Man, has a somewhat similar narrative structure, a narrative relay passing from one character to the next (though so do Luis Buñuel’s The Phantom of Liberty and Richard Linklater’s Slacker, among other arthouse examples).

Other mainstream movie counterparts come as readily to mind. In more ways than I can count, The Circle is also like a punchy Warners proletarian-protest quickie of the 30s, with salty convicts, a hard-nosed, self-accepting prostitute who could have been played by Joan Blondell, snappy extras, and a kind of narrative pacing — the way characters drift in and out of the plot — that evokes the way traffic moves on a busy city sidewalk. (Parenthetical query: are American movies made before we were born “ours” or “theirs”? Answer: I think they can become ours if we decide to adopt them.)

The movie begins and ends with two virtuoso long takes, both 360-degree pans that define the poetic and metaphoric limits of Panahi’s universe and are so overloaded that they threaten to explode the film’s structure. In the first, a baby is being born offscreen in a hospital, her mother howling with pain, and when a nurse reports through a window in a door that it’s a girl, the grandmother, speaking on the other side, is clearly upset — “But the ultrasound said it would be a boy!” — and continues to worry about the expected anger of the in-laws as she goes downstairs and speaks to another daughter. The latter leaves the hospital, passing three women beside a phone booth — all former prisoners who quickly take over the narrative. In the last shot, a prostitute enters a jail cell where virtually all the major characters in the film, excluding the grandmother, are revealed over the course of one lengthy circular pan. When a nearby phone rings, and a guard appears at a window on the cell door asking for a woman who isn’t there, but is apparently in an adjacent cell, the name is that of the mother whom we heard giving birth in the opening shot.

Simply put, Panahi’s film is about Iranian women who aren’t free — free to ride on buses or stay in hotels without IDs, free to walk down the street alone or enter some places without chadors or hitch rides or smoke cigarettes in public (a running gag as one character after another tries to light up) or have abortions or function as single mothers or be let off easily by the cops (unlike some men we see). And for all the artificiality of the bookend shots, and the many circular paths in between that are charted (and doors with windows that are peered through) — not to mention a narrative comprising a catalog of abuses — the surface textures of this film are every bit as real and as immediate as those in The White Balloon and The Mirror. Moreover, the fact that it’s so blunt and effective makes some people furious, Iranians and non-Iranians alike — because it’s axiomatic that political provocations tend to put us all on the spot and make us angry or defensive, sometimes both.

***

To hear Panahi tell it, The Circle isn’t political at all and this story could be set anywhere; that’s what he insisted when I met him at the Toronto film festival last September, and what he has said on several other occasions. For me, calling The Circle apolitical is tantamount to insisting that pork is a vegetable, but considering all that Panahi has had to contend with for having made it, it’s hard to fault him for saying such a thing, and it’s even likely that he believes it.

It may only be a matter of semantics — a question of whether or not humanism qualifies as a kind of ideology. “A political filmmaker commits to a certain ideology, tries to propagate that through his work, and attacks opposing ideologies,” Panahi has said. “In The Circle, I am not attacking or supporting anyone. I am not saying who’s good and who’s evil. I am trying to look at everyone from a humanistic point of view and hold a mirror that reflects social realities. It’s up to the audience to interpret those realities in political terms if they wish to do so. I have made an art film with a message of protest, not a subversive political film.”

One thinJonathan Rosenbaumg that’s pretty clear about both Panahi and his movie, regardless of whether you think they’re political or not, is that both are unreconciled, perhaps even unreconcilable. Panahi fought for years before receiving script approval from the Iranian government, and it seems likely that he never would have gotten it without the prestige of his two previous features. The film still doesn’t have a screening permit for showings in Iran, and reportedly has been shown there only once — at a secret screening planned for 25 students, though according to Panahi, “400 students showed up” and “their reaction was very positive.” He rejected a proposal last year to show it at the Fajr film festival in Tehran with the final 18 minutes removed, but wound up showing a video of the uncut version in his house to foreign guests. This has encouraged some Iranians–including many liberal-minded ones — to accuse him angrily of tailoring his film for the West and reinforcing the stereotypes of Westerners about Iranians.

This is part of the gist of an attack by two women studies professors writing last March in the Montreal Gazette, Roksana Bahramitash and Homa Hoodfar, who define “three distinct kinds of problems for those of us intent on familiarizing people with the realities of women’s situation in the Muslim world. First, it ignores completely the multiplicity of women’s acts of resistance to and subversion of oppressive practices. Second, it presents the story of Iranian women as one of continuous defeat. As a result, they seem in dire need of a white knight to ride in from the West, much as the Crusaders did, to rescue them. Third, it compromises Muslim women’s position and poisons the atmosphere among family, friends and community. When one of our teenage daughters saw the movie, she whispered: `I will never go back to Iran’ because of her shame about being Iranian.”

This sounds like another form of the “them” and “us” discourse alluded to earlier — some of which may seem unavoidable, though I must say it still gives me the creeps. But if people are going to make charges of this kind against Panahi, they might as well be more precise and say that The Circle is tailored specifically for Westerners who tolerate cigarettes and abortions, and find virtue in unhypocritical prostitutes. But how seriously would we take anyone who charged, say, William Faulkner with tailoring Light in August for Yankees and French intellectuals? I assume it must cater to Iranians, because I’m told it’s easier to find several Faulkner novels in Persian — including this one — than it is to find any Iranian novel in English. Since it’s my favorite novel in any language, I harbor the fantasy that some Iranians, some other Americans, and I might like it for similar reasons, regardless of all our other differences — and that’s an “our” unlike the one proposed by Bahramitash and Hoodfar that I can fully endorse and respect.

I hope they’ll forgive me for saying that the problematic responses to The Circle they cite are precisely the sort of thing that complex works of art tend to foster; I’d hate to hear the shellacking King Lear might get from critics who point out how unfair it is to grateful children and humble patriarchs, among the types that Shakespeare overlooked. Obviously, there’s always a price to pay for expressing negativity about the state of things. But it strikes me as unthinkable that Panahi himself would ever express shame about being Iranian, whatever his quarrels with the Islamic Republic, and highly unlikely that any white knight — a stereotyped version of my ethical self-image that I find abhorrent, whether it applies to other Western white males or not — could offer the blazing light provided by Panahi’s measured detachment as well as his anger. Furthermore, to suggest that the women he shows are all “defeated” is a reductive summary of a story where solidarity between women, shown in varying degrees throughout, surely counts for something, along with highly visible signs of pride and defiance. (One of the first things we see in the film is a woman aggressively berating a passing male on the street for asking her and a friend, “You two alone?” — not exactly the behavior of a passive victim.) And I’m afraid these academics give the game away when they add, “Interestingly, the movie was made by a man, evidently seeking Hollywood success.” I’m not holding my breath while DreamWorks offers Panahi an exclusive contract; but given that he doesn’t speak a word of any language except Farsi, I can’t imagine what he’d want to do with one if they did.

“There are many other Iranian movies, technically and aesthetically of higher quality,” they continue, “which present a far more accurate picture that have received no acclaim in the West.” Since they refuse to divulge a single title, thereby making their argument impossible to refute, I’ll be presumptuous and cite one myself that happens to be showing for free on the Northwestern campus this Wednesday — Divorce Iranian Style — and tied for fourth place on my ten best list for 2000. I wouldn’t call it “technically and aesthetically of higher quality,” and it may be further disqualified by having received at least a modicum of acclaim in the West. But since it’s a masterful documentary made by two women, one of them Iranian, I see no point in ranking it alongside Panahi’s masterful work of fiction as if the two were comparable. Suffice it to say that it’s wonderfully attentive to “the multiplicity of women’s acts of resistance to and subversion of oppressive practices,” presents the story of Iranian women as one of frequent — if not continuous — triumph against impossible obstacles, and beautifully complements The Circle without in any way challenging or negating what it has to say.

Of course Panahi doesn’t give the whole picture of women in Iranian society. Who could, and who would want to? Light in August doesn’t begin to offer the full range of Mississippi society, either, and its own rage about racism — which must give a certain amount of unwarranted solace to glib Yankees — also has to be judged for the emotions it stirs in the rest of us. Southerners who call those feelings defeatist, provoking embarrassing shame in their children, are being just as parochial as everyone else — including me, who finds it both exalting and tragic, beautiful and caring, measured and unreconciled. Like many works of art, it can and should affect many people differently.

***

Since we’re no longer living in a Cold War, I hope it’s still possible to criticize this country’s government without being labeled a potential terrorist. That must sound hyperbolic, but only because I’m lucky enough to not be an Iranian. According to our state department, simply being an Iranian automatically makes one a potential fundamentalist terrorist, regardless of whether or not one is critical of this country — and even regardless of whether or not one is a fundamentalist. In this respect, at least, one has to concede that “their” regime may be better than “ours,” because even though Iranians hear about Americans such as McVeigh and Dahmer, not to mention countless trigger-happy teenagers with handguns, “their” officials are sufficiently trusting and respectful–that is to say, civilized — not to fingerprint and take mug shots of American visitors to Iran.

But that’s what U.S. custom officials routinely do to all Iranians crossing our borders. When a movie by Majid Majidi was nominated for an Oscar, he was fingerprinted and photographed en route to the Academy Awards ceremony he was invited to attend. (Maybe they were afraid he might shoot Billy Crystal if he didn’t win.) The same year, Darius Mehrjui, one of the pioneers of the Iranian New Wave, met the same humiliation with his Harvard-educated wife and their two-year-old son, en route to a retrospective of his own work at Lincoln Center, where he’d been invited jointly by the Human Rights Watch Film Festival and the United Nations. Still in a state of shock, he and his wife decided they’d rather fly back to Iran instead–only to be told that they couldn’t do that unless their fingerprints and mug shots were taken first. Why? Because, it was explained to them, they were already on American soil and thus subject to American laws.

Why do our customs officials — or more precisely, the blowhards dictating their policies — insist on being so obnoxious? I can’t believe it’s always been this way or that it hasn’t been a coarsening of behavior brought about by the increased and largely market-imposed isolationism of American culture. “Lately,” Gore Vidal wrote in Vanity Fair in 1998, “I have been going through statistics about terrorism (usually direct responses to crimes our government has committed against foreigners — although, recently, federal crimes against our own people are increasing). Only twice in 12 years have American commercial planes been destroyed in flight by terrorists; neither originated in the United States. To prevent, however, a repetition of these two crimes, hundreds of millions of travelers must now be submitted to searches, seizures, delays.” And it appears that Iranians and Cubans get treated with particular callousness. The Iran hostage crisis during the Carter administration is probably a major reason for this behavior — a crisis that, in keeping with Vidal’s point, was partly a response of fundamentalists to the CIA-orchestrated coup ousting Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953.

In any case, Panahi got so sick of being treated like a criminal every time he came here — and he’s been here many times with his films — that he finally chose to stop coming if he had to go through it all again. This led to special waivers of this practice when he attended the New York Film Festival with The Circle last fall and the National Gallery somewhat later, but not any more since George W. has assumed office, even if Panahi’s only changing planes. I kid you not. When Panahi was recently flying from Hong Kong to South America to attend a couple of film festivals, and had to change planes at JFK, United Airlines assured him that he wouldn’t have to submit to the usual insult “we” dish out impartially to all Iranians, regardless of race, creed, or color. But United was mistaken, and when Panahi refused to cooperate, he was shackled to a bench for over a dozen hours in a room full of illegal aliens, not allowed to phone anyone, and then sent straight back to Hong Kong with his hands and feet in chains, even after he showed evidence of who he was and where he was going. After all, the fact that The Circle won the Golden Lion in Venice last year doesn’t mean he might not have managed to sneak a hand grenade through the metal detector in Hong Kong.

One can argue that Panahi, a man with an evident martyr complex, should have put up with the minor nuisances and not been such a diehard — though if he’d done that, it’s unlikely the rest of us would have ever heard any of the above stories (recently reported by stateside teacher and filmmaker Jamsheed Akrami). I can’t imagine Bahramitash and Hoodfarit condoning what happened, but it does seem ironic that the man who allegedly caters to American prejudices about Iranians and “is evidently hankering after Hollywood success” suddenly gets treated like a dog when he passes through one of our airports. Yet it also seems terribly consistent, because those who condemn Panahi for raising a ruckus, either through The Circle or in American customs, are essentially saying the same thing: “Sit down, you’re rocking the boat.” Or, “Who do you think you are, an American?”

So what should we do? Should we applaud Panahi for protesting injustice wherever he finds it? Or should we call him an asshole for protesting when he finds it over here? And how should we feel when he forces us to become aware of a practice that most of us know less about than the chadors Iranian women have to wear? Maybe this man is a terrorist after all — an emotional terrorist whose project is to upset us, and whom most of us are determined to ignore as a consequence.

I realize that the referents for “we” and “us” in the above paragraph keep shifting, meaning something different with every usage. But I’d argue that’s what often happens when we use those words, especially when they have national, racial, and ethnic referents, and it’s only when boat-rockers like Panahi come along that we even begin to notice some of the problems and impostures involved. If we’re all simply Westerners looking at Iranians in The Circle — “us” looking at “them” — we can’t be paying much attention to what the film is doing, which also has something to do with an Iranian looking at Iranians, among other things.

One of the festivals Panahi had been heading for, which he never reached, was one I was attending in Buenos Aires, and when his own account of his ordeal went out in English on the Internet, I spent some time with Mark Peranson, the editor of the Canadian magazine Cinema Scope, in the festival’s cybercafé, trying to find what American newspapers, if any, had bothered to report the incident. At that point, none had, though the L.A. Times and Village Voice ran stories a bit later. Typically, the New York Times decided around that time that the jokey putdowns of Otto Preminger’s Exodus by Miramax’s Harvey Weinstein were what its urbane readers who followed movies really needed to know.

***

Getting back to personal pronouns, it’s worth asking, finally, whom The Circle belongs to. Although it may have been authorized in part (and with difficulty) by the Islamic Republic of Iran, one clearly can’t claim it belongs to them, especially if “they” won’t allow it to be shown. And one can’t say that it belongs to “the Iranian people” either — not if many of them are so vociferous about disowning it. Does it belong to the Westerners some Iranians (and Westerners) claim it was tailored for, most of whom haven’t seen it? Or does it belong to the Iranians who can’t see it, some of whom wouldn’t like it if they did?

The problem, however, isn’t nearly as acute as I’m making it sound. In fact, there are many people all over the world who feel passionately about The Circle, and their numbers become even more apparent once we drop this antiquated nationalist jargon and silly tribal chant and recognize that some of them are in the West, some are in the East, some are in the Middle East (including Iran), and some are even in the Midwest. I also know some Iranians in North America who like it. We might even constitute a community of sorts, though some of us may not know this yet. I daresay there are a significant number of us on the planet who would be happy to call this lovely and mysterious object our film, at least if other people let us. In fact, though I don’t speak a word of Farsi, I can’t think of a movie I’ve seen anywhere over the past year that speaks to me as directly or as powerfully. I certainly haven’t seen any shot as breathtakingly beautiful or as dramatically satisfying as the long take of the prostitute (Mojhan Faramazi) sitting alone in the police van after a male prisoner has successfully offered cigarettes to the two cops riding in front, one of whom had previously told her to put out the cigarette she was starting to light. (It’s apparently easy to smoke most places in Iran if you’re a man.) Taking a furtive glance around her, and coming to the realization that she can finally light her cigarette in peace because no one will mess with her now or even notice, she looks out the dark window and takes a drag while the night rolls past.

Maybe there’s something important about the fact that Panahi, I, and several others have a film and certain emotions about it in common, even though we don’t share a country, a government, a language, a set of laws, a definition of politics, or even the same treatment at the hands of American customs officials. At this particular moment in history — when this country, according to some of “our” leaders, is supposed to be the only one that truly exists or matters — I’d say that’s a meaningful start of something, even if the middle or end of it still isn’t in sight.