A recent essay. — J.R.

Reflections on Kiarostami’s Two-Way Mirrors

Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa

“The power of cinema is to create believable illusions.” Abbas Kiarostami

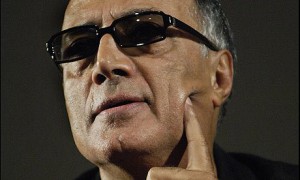

As I begin to write about Abbas Kiarostami’s cinema, my profound sadness about his loss emerges again. The vivid memories of several meetings and conversations with him in different countries (Iran, Europe, Canada, and the US) and at different times and on various occasions in the last four decades are now mixed with images from his films. How ironic that his death happened so abruptly, like the many unexpected and unresolved open-endings of his films.

The filmmaker I was fortunate to know was a graceful, thoughtful dignified man, observant and playful with a great sense of humor. Despite his fame, he was very humble. He was very supportive of other filmmakers, new directors, and especially his students in many of his workshops around the world.

I remember meeting him for the first time in Tehran after the screening of his second feature, The Report (Gozaresh, 1977). The dark bleak film had very little resemblance to its warm friendly-looking approachable serene director who always wore a sweet smile when greeting people.

During the year 1980 I’d run into him from time to time whenever I went to Kanun (The Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults) to resolve the production issue of my unfinished film, The Transfigured Night. Those days, I was extremely stressed and upset about the film industry and the frustrating nature of filmmaking and the fate of my first film that was interrupted due to the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988).

Kiarostami’s kind smile greeting me in the hallways of Kanun was the only consolation for me who had to face a dozen angry producers in my production meetings there. Years later, after studying Kiarostami’s films, especially his shorts, I realized how being insightful and innovative could simply ease up or even solve many of the common film production difficulties, in particular the ones I had been facing. His films, in particular his early shorts, made at Kanun with very low budgets, non-professional actors, simple settings, and minimal storylines, achieved much greater impact and had more sophisticated artistic qualities than those made within conventional industry norms. With these films, he showed that the challenge of artistic filmmaking is mostly a matter of vision and not so much one of budget.

My appreciation for his inspiring and innovative cinema grows deeper as the years go by. He had a unique vision in his films and in his artwork, that was deceptively simple yet hard to copy, like that of Parajanov.

He always stayed true to himself, to his creative impulses, striving to fulfill his own artistic urges and curiosity rather than following certain modernist fashions in filmmaking. In this way, he challenged many stereotypes and clichés of conventional representations of people and their stories on screen.

The Amateur

Similar to Jean Rouch who after making more than hundred films called himself an amateur, Kiatrostami also preferred to consider himself not a professional but an amateur—a novice and an unskillful beginner who is learning about filmmaking is experimenting with it, free from the demands of the market and the common formulas of conventional storytelling.

At times, he expressed his interest in poetic possibilities of cinema and believed that film should be open, unfinished, and open to multiple interpretations, like poetry.

He loved working with young film students in his many workshops that he led around the world and always considered them as his teachers. He said that making shorts alongside his students brought him close again to his initial love for cinema and provided a break from his features. (Many transcripts from those workshops and classes are usefully included in Paul Cronin’s recent book, Lessons with Kiarostami)

Not having a film school training, being a painter and graphic artist (before entering the field of filmmaking at Kanun to make educational films for children) and not being expected to make art or commercial films when he first started there, became his asset and gave him freedom to explore and make his own kind of cinema.

He was never spoiled by his international success and did not fall into repeating himself in his films. In fact, every film represented a new challenge and agenda for him. (Long before he was discovered by Cannes Film Festival in 1992 for his Life and Nothing More, he was well established inside and outside of Iran for two decades and had made more than 22 films (shorts, medium length, and features).

His work has light to heavy philosophical tones (echoing Dostoyevsky and Beckett) and is influenced by Persian poetry (from Forough Farrokhzad to Omar Khayyam, Sohrab Sepehry, and Rumi) ranging from quite serious dark films to ones that are more carefree, playful, and often both bleak and humorous at the same time.

Some of the Major Characteristics of Kiarostami’s Cinema:

The Characters:

There’s a sense of poetry in most of Kiarostami’s films that comes through his characters and the way he portrays them in his films, revealing their truths and their inner beauty which are at times hidden behind their borrowed identities.

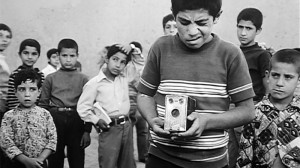

The deprived rebellious young boy in The Traveler (Mossafer, 1974) who only cries in his sleep, the rows of little boys whom he photographs with his empty broken camera, the poor tough boy in The Wedding Suit ( Lebassi Baraye Arusi, 1976) who wants to look rich by wearing a suit that doesn’t belong to him, the young boy who shows great acts of love for his friend in Where’s the Friend’s Home (Khaneye Doust Kojast?, 1987) , the innocent, impoverished, small criminal Sabzian in Close-up, the innocent looking young boy who helps Behzad in The Wind Will Carry Us (Bad Ma Ra Khahad Bord, 1999), the worker who collects plastic in Taste of Cherry (Ta’m-e Guilas, 1997), the persistent naïve and romantic Hussein in Through the Olive Trees (ZIr-e Derakhtan-e Zeytun, 1994) , or the many traumatized small boys in Homework (Mashgh-e Shab, 1989) , who are subjected to physical punishment and shame by their families and their teachers, are some of the examples of his unforgettable characters.

“The Shortest Way to the Truth is a Lie.” Abbas Kiarostami

Most of Kiarostami’s beloved characters are innocent liars. The young boy in The Traveler is portrayed as a sympathetic small town adolescent who dreams of going to Tehran to watch a soccer game. He tries to raise the necessary funds to go to the game by stealing from his mother and cheating school children by taking their photographs with his broken empty camera. We disapprove of his actions but feel sorry for him, especially when he is beaten by his school teacher.

An adult version of him appears in Kiarostami’s masterpiece Close-up (Nama -ye Nazdik, 1990) as Sabzian, an impoverished unemployed man who impersonates Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a famous film director. In fact, the same theme music played in Traveler is also used at the end of Close-up, reminding us of the boy’s tribulation and tragedy in The Traveler.

The last in the series is the young innocent looking Japanese woman in Like Someone in Love (2012), a prostitute.

In his earlier films, Kiarostami, shows how the children resort to lies in order to survive. They are subjected to a system of terror and torture and humiliation by their families and teachers, are afraid and ashamed of criticism, and are beaten by the adults.

The heartbreaking images of corporal punishment as a method of discipline that we see in Breaktime (Zang-e Tafrih, 1972), Experience (Tajrobeh, 1973), and in The Wedding Suit, emerge again as a pivotal part of The Traveler in two scenes. The first one appears early on in the film when the boy is being beaten by the principal. We then go to the classroom where the teacher is busy drawing a big heart on the blackboard. The loud sound of boy’s cries is heard but no one in the classroom dares to react to it. The second image of beating comes at the conclusion of the film in the boy’s silent dream scene.

Kiarostami focuses on the fear and the pain of corporal punishment on a mega scale in Homework. These children often lie in front of the camera. But through their interviews with Kiarostami we realize that lying is their only defense to survive in a family and society based on shame and fear. The film also provides a profound philosophical insight into the root of political violence by including many references to the Iran-Iraq war. We see how some of the boys in their interviews express their desire to become revolutionary guards in order to kill the criminals or fight in the war to slay Saddam when they grow up. Early on in the film when they are lined-up to go to their classrooms they are led by the principal to perform their morning rituals of physical exercise and chanting religious and revolutionary songs against Saddam, the enemy.

Kiarostami had a remarkable understanding of the children and a unique insight into the personalities of his adult characters in his films.

He also had a special talent and skill in directing them. He would spend a long time with his non-professional actors to make them believe in their parts, coming up with authentic lines of dialog before he would start shooting. In many of the car scenes of his films in fact it’s Kiarostami who is behind the wheel asking questions of his passengers and not his protagonists. In The Wind Will Carry US, when the school boy responds to Behzad’s question if he is a good man or not, or the village man talks about the mourning ritual, they are both responding to Kiarostami. Also in Taste of Cherry, all three characters who are picked up by Mr. Badii and get into conversations with him, are in fact talking to Kiarostami who is driving the car.

Self-reflexivity, Transparent Mirrors

Most of Kiarostami’s films have a mirroring function both for him as the filmmaker and for us as the audience. We see ourselves in his films as he looks at himself in them.

The Filmmaker

He appears in front of his camera in Close-up and Homework or represents himself through his main characters (his alter egos) in Life and Nothing More (Zendegi Va Digar Hich, 1992) , Through the Olive Trees, Taste of Cherry, The Wind Will Carry Us. Sometimes, we only hear his voice talking to his film crew (Orderly or Disorderly) or interviewing his subjects (Close-up, Homework).

In this way, he is commenting on his role as a filmmaker, often in a critical fashion. This aspect of Kiarostami’s self-criticism is a significant part of his cinema.

In Close-up, we see how the policemen respect Kiarostami, how he is allowed to shoot in the court, and how he becomes part of the trial, interrogating Sabzian although in a sympathetic non-judgmental way. We witness the power of a celebrated director and understand why Sabzian in his failed attempt wanted to act like one.

In The Wind Will Carry US, we are presented with Behzad, a documentary filmmaker who has no regards for the villagers, the dying woman, or the magnificent nature around him.

The Audience

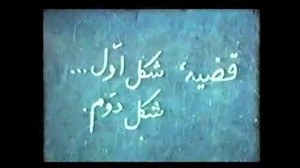

Kiarostami always plays with the concept of the audience in his films. For example, in Case No. 1, Case No. 2 ( Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Avval, Shekl-e Dovvom, 1979), Close-up, Where’s My Romeo, and ultimately Shirin (2008), he includes his audience. He also addresses his audience directly through his camera. The most obvious examples are in The Report and in The Wind Will Carry Us, in which, his characters, Firuzkuhi and Behzad, while washing and shaving, look directly into the camera; treating it as a mirror and confronting us. At times, the mirroring effect is more subtle, and is achieved through the structure of the film and his elliptic style in storytelling, which makes us aware of ourselves and our expectations of the film.

The Incomplete/Imperfect Cinema

Kiarostami insisted on calling his cinema an imperfect cinema since his films, in opposition to those made in Hollywood, had gaps in their stories, did not provide the expected information about their characters’ motivations and had no clear resolution or closure. Thus, creating a space for his audience participation to use their imaginations and creativity to fill out the missing parts and interpret and shape the films as their minds see fit.

A good example of this approach can be seen in Taste of Cherry, where the audience has no idea why the protagonist is contemplating suicide or why he needs to be buried once he is laid dead in his grave. In Like Someone in Love, what happens between the young woman and the old professor is left to our imaginations and desires.

When suddenly the professor starts caring for the young prostitute like her father we are not sure why in the first place he called for her. This shift from her client to her father figure is not explained.

Similarly, in Certified Copy, when halfway through the film, the writer and this hostess act as a married couple, we have no clue. We are puzzled and wonder if they were married before and if what we see is a flashback. We could also conclude that the second part is real and the first part is a fantasy or vice versa.

On certain occasions, the gap happens in the sound track that makes the audience wonder what they are missing. For example, the final scene of Close-up where Sabzian meets his ideal, Makhmalbaf, we want to know what they are talking about but Kiarostami interrupts their dialog several times with the false excuse that the sound equipment is not working properly.

In Ten (Dah, 2002) we are inside a car, seeing only the driver and the passenger. This is one of the most essentialist films of Kiarostami, made without a film crew and with minimal directing. Hiding himself behind the back seat, he only fed certain lines of dialog to the driver (Mania Akbari). Here, the exterior environment is only seen through the car window. The two digital cameras fixed on the car dashboard, one on the woman driver and the other one on the passenger side, show all we need to see or hear. In the case of the intoxicated passenger, we only hear her voice as she is speaking to the driver. Similarly, in The Wind Will Carry Us, we never see the crew throughout the film, but hear them talking.

The use of off-screen sound and the idea of sound replacing image becomes more significant in the films made after Ten. In his bold, monumentally minimalist and illusionist film, Shirin, we are shown a group of isolated women who are watching a movie that we don’t see. The off-screen movie is about Khosrow and Shirin, a medieval classic triangle love story, that is based on Nezami Ganjavi’s poem, accompanied by a magnificent Iranian score.

Kiarostami used three chairs in his house to film the close-ups of 110 of the most famous Iranian actresses as well as Juliette Binoche. (A fantastic response to those who criticized him for never using any Iranian professional actresses in his films.) He instructed them to sit and look at a blank sheet of paper fixed next to the camera and think about memories of their romantic relationships or their favorite romantic movies for six minutes. Later on, he created and added the sound of the imaginary/invisible movie (voices and the music) to the images of these women as its audience.

Here Kiarostami demands his audience to imagine a whole film that they don’t see. We hear the sound track of the invisible movie and try to imagine it in our minds while watching its audience–the women who are presumably viewing the film and reacting to it.

Interestingly, this geometry of looking created in Shirin that divides our attention between the invisible movie and its audience, the women we are seeing on the screen, echoes the triangle love story of the off-screen film.

The spectacular historical film score and the multi-level soundtrack of the invisible film suggest an epic, a film that could possibly have many extreme long shots. But what we see are only close ups of its audience. Kiarostami had already played with the concept of Shirin in his short, Where’s My Romeo (2007), where he used the sound of Romeo and Juliet (Franco Zeffirelli, 1968)

With Shirin, Kiarostami also pays his tribute to the Iranian voice artists by casting talented narrators (led by Manoochehr Esmaeili) and Iran’s master musicians such as Morteza Hananeh and Hossein Dehlavi.

We see another intriguing and brilliant example of using off-screen sound and on-screen space in Like Someone in Love. In the opening scene we are introduced to a bar in Tokyo at night. In the center of the frame there is an empty chair, representing an absence or anticipating a forthcoming entrance. We hear the voice of a young woman talking (saying “I’m not lying ton you”). Not seeing her for a good seven minutes creates a sense of mystery and discomfort. It also draws our attention to the off-screen space (extending the frame) and makes us conscious of an absence. Later, when another woman in the bar starts to talk, our confusion about what is happening turns into curiosity and a sense of anticipation that directs our attention to different parts of the screen. (Echoing the opening scene of Certified Copy, where we are shown a podium with two microphones. Both the audience in the film and ourselves are waiting for a speaker who is absent.)

“I see thousands of people who are myself

Yet they keep thinking they are themselves.” Rumi

One of the best examples of how Kiarostami creates a multi-layered echoing/mirroring effect is in Close-up. Here with the Borges’ labyrinth hall-of-mirrors-like structure and an elliptic narrative he reveals the truth about the characters of his story and his role as the director of the film. We also see how everyone in one way or another is caught in the deceptive power of cinema.

In Close-up Kiarostami revisits the idea of lying not only to display the reality about his characters (and their agendas) but also to comment on the inherent artifice of cinema in exposing the truth through fabricating and manufacturing realism and realistic illusions.

Close-up with its theme of cinephilia in Iran and the corruptive possibilities of cinema in the lives of ordinary people, influenced many generation of filmmakers and changed the course filmmaking in Iran after 1990.

In the beginning of the film we see the journalist entering Ahankhah’s house to arrest Sabzian. We expect to follow him inside but instead, Kiarostami keeps us outside, making us pay attention to the driver who is waiting for the journalist. We observe his casual conversation with the two soldiers in his car and later on we see him, bored, kicking an empty spray can down the street. Not being able to see what is happening inside the house creates a break, disconnecting us from the story, which leads us to become more aware of ourselves and our expectations of the film. Kiarostami show us what we want to see in a later part of the film, thus creating a sense of displacement in its narrative organization. He also treats his characters in a similar fashion. They are either inadequate for their tasks or are wrongly assigned to do them.

If Sabzian does not have the means to become a famous director, the journalist doesn’t have a recorder to do his job either and the taxi driver is a pilot who has now become a driver to earn his living. It seems no one has the right tools/equipment to do their jobs. Even jokingly at the end of the film, we hear Kiarostami talking to his off-screen crew saying that Makhmalbaf missed his mark and did not stand where he was supposed to. Makhmalbaf knew he was going to meet Sabzian at the end of the film but Sabzian didn’t know. Their meeting thus became both real (documentary) and fake (staged). In fact, Sabzian’s surprised reaction at seeing Makhmalbaf was more authentic than Makhmalbaf’s response to meeting him. Close-up with its non-linear structure and its shifting points-of-view constantly builds up and breaks our expectations and blurs the border between fact and fiction. What looks like a documentary film is in fact a work of fiction. In fact, the trial was shot several hours after the judge left the courtroom and all the people involved in the story had to re-enact the events in order to produce the story for the camera.

Kiarostami shows his power as a director who is respected throughout the film. This becomes a context for us to understand the motivation behind the powerless Sabzian’s action to impersonate a famous director like Makhmalbaf. It also makes us see the roles of filmmakers and cinema in the lives of people in Iran: the fact that cinema in Iran became not only the main form of entertainment but also proved to be a medium that could make you famous and powerful overnight. Obviously, the power of celebrities is not unique to Iran as Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982) also attests but in Iran the celebrities can also become influential social and political figures. The phenomenon of Makhmalbaf was a good example of that. If during the 60s and early 70s a youth wanted to become a poet, in the 90s the majority of youths wanted to become film directors.

The characters in Close-up all mirror Sabzian in one way or another. The journalists who are excited to become famous by writing the story of Sabzian, the Ahankhah family who welcomes the fake Makhmalbaf and later on Kiarostami, even the soldiers who walk into the frame in the beginning of the film, all want to be in the film and be seen, reminding us of the row of children who want to be photographed by the empty camera of the ambitious teenager in The Traveler.

A Meditative Cinema

There is a painterly (1) and meditative quality to most of Kiarostami’s images, in particular those films with landscapes that often reflect his views about life rather than those of his characters.

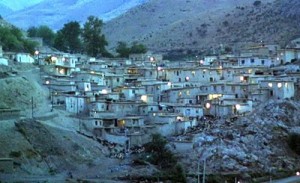

In The Wind Will Carry Us, we are presented with magnificent paradise-like images of Siah Darreh in Kurdistan, like those of the dreamy village in Brigadoon (Minnelli, 1954) that Behzad, the protagonist, does not pay attention to—a commentary on his lack of awareness and his obsession with his job and with filming the death ritual.

In Life and Nothing More (1992) we see the director’s point-of-view of looking at a beautiful landscape through the ruins of the village house that is destroyed by the earthquake. His camera zooms pass the ruined doorway into the gorgeous views of the trees and the vast green space.

And in the last scene of Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003) he focuses on the reflection of the moonlight on the dark water at night. In both Certified Copy (Copie Conforme, 2010) and Like Someone in Love (2012) we see the reflection of the environment (sky/trees/roads, street lights) on the window of the moving car, a dominant image that makes us detach from the story and pay attention to the off-screen space that is reflected in the frame.

In The Birth of Light (Tavalod-e Nur, 1997) his still camera celebrates how the movement of sunrise generates an image of a mountainous landscape. In ABC Africa (2001) when the electricity power is gone, in Taste of Cherry when Mr. Badii lies in the grave, and in Five, where we only hear the frogs sounds, it’s the dark screen that forces us to reflect on what is missing: the image, the light.

More recently, I saw a short from his latest project, 24 Frames Before and After Lumiere, that displayed two black horses playing in heavenly white snowy landscape, viewed through a car window. The highly meditative composited image looked like a painting in motion.

Metaphors and Philosophical view

A fascinating characteristic of Kiarostami’s films is how he creates metaphors within his films and how he manages to draw our attention to larger concepts by his precise observation.

The car windows in many of his films including Taste of Cherry, Ten, Life and Nothing More, Certified Copy, and Like Someone in Love act as transparent barriers that separate the interior/private space from the exterior public environment. Similar to a film camera, the windows frame people and landscapes/environment that appear through them. Also, the large window of the old man’s apartment in Like Someone in Love provides a view for the old man and a false sense of security and separation from the outside world for him that can be easily broken. Here, the large window also acts as a film screen at the end where a piece of rock breaks it and the film abruptly ends with a loud, unexpected sound.

At times, Kiarostami creates metaphors by concentrating on the details of a scene, objects, and their shapes, or simply by the way he uses shadows, darkness or color.

In Solution (Rah Hal-e Yek,1978) a lonely man on the side of a road decides to walk to his broken car when no one gives him a ride. He pushes his spare tire and walks behind it. But soon the wheel speeds up as it rolls down the road, leading the way and making the man run after it until it finally reaches his car. This simple existential film about the man’s loneliness turns into a surrealist piece when the tire becomes a character that knows where to go and how to turn on the edge of the winding road.

Kiarostami revisits the mechanical and autonomous movement of objects in his later films such as the rolling of the empty spray can down the street in Close-up, or the fallen apple in The Wind Will Carry Us, and the bouncing ball in Take Me Home (2016).

These trivial and apparently unimportant observations of the paths of movement could be seen as the director’s philosophical views about life’s journey.

In each of his films, his characters are connected to an object. In The Wedding Suit, the suit of the rich boy becomes a metaphor for a different identity–being rich–that cannot be borrowed, representing an impossible class mobility, a dream that turns violent, as indicated by the drop of the poor boy’s blood on the new suit.

The piece of human bone that is carried by the protagonist, Behzad, in The Wind Will Carry Us, adopts several meanings at the end when he throws it into the stream. His action can indicate that he has learned his lesson and has reached a new level of awareness. And the floating bone going down the stream can be seen as the director’s comment about life and death.

Kiarostami has a unique interest in framing the curvy and zigzag paths and the movement of people, cars, and objects in them.

The zigzag roads in Where’s The Friend’s Home and in The Wind Will Carry Us and the repeated action of Behzad going up the hill to get a better reception for his cell phone, the final shot of Through the Olive Trees and Life Goes On are good examples of his kind of formalism to informs us about his philosophical views of life.

His interest in philosophy and poetic symbolism of the roads is best summarized in Roads of Kiaostami (2005). The beautiful roads shockingly end with an image of atomic explosion that burns the last image of the film, the shot of a dog looking into the camera. As the image burns, the blackness fills the screen, making a strong statement about the destructive power of a nuclear bomb that threatens life on earth.

But his philosophical view about the world does not often come as clear and straightforward as in The Roads of Kiarostami. In fact, at times, it is presented to us in a complicated or contradictory way, by offering two ways of seeing an issue, or a relationship (turning one version as a metaphor for another) while playing with our assumptions about fictional and documentary cinema, challenging our expectations and assumptions about them.

In Orderly or Disorderly? (Be Tartib ya Bedun-e Tartib?,1981), we are faced with the two possibilities of people’s behavior in public spaces in terms of respecting or disrespecting social order. In both sections, disobeying the rules of traffic and ignoring the rights of others generate chaos. (Thanks to the shot compositions, hence reference to Tati, and the conversation of Kiarostami with his crew over the shots, they become hilariously funny).

Here the citizens and the system show mutual disrespect for each other. The pedestrians who ignore the cars, the cars that do not pay attention to the traffic light, and the traffic police who could not or would not maintain the order reveal an entangled social situation. In the conclusion of the film, we hear that the filmmakers are unable to take even one single orderly traffic shot and that it’s impossible to get such a shot in any part of the city. Kiarostami and his crew, who are off-screen, become part of the story and we hear their conversation. Our attention is divided between what he shows (in front of the camera) and what he doesn’t (behind the scene) or what we hear.

One of the brilliant moment of the film is when the school boys taking a long time getting on a bus are vshown to us from a distance. The time code on the long shot emphasizes the length of time for them to get on the bus. But when we cut to a close -up (on the other side of the street, the reverse angle) we see how the boys have jammed the entry to the bus by not respecting the order in the line. This simple cut not only creates a hilarious comic moment in the film but also comments on the two ways of seeing an event.

Realism

There’s a strong sense of realism in Kiarostami’s cinema that comes from the choice of settings and his non-actors as well as his style of filming and the look of his films.

In many of his interviews he talked about how he would spend a long time finding the right settings for his films. For example, he spent months to find the apartment for the middle-class family for The Report and the right village for The Wind Will Carry. Also, he would make sure that the appearances of people were realistic and not altered for the sake of his films.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, he would not change the look of his settings or the clothing of his characters. Interestingly, he makes a reference to that kind of filmmaking in Through the Olive Trees, where the director in the film insists that the young village woman, Tahereh, should wear a local traditional dress (against her will). In fact, it’s often in a Kiarostami’s film like Taste of Cherry that we can see a worker wearing a UCLA T-shirt. What also contributes to the realism of his films, in particular those made in Iran, is his insistence on exposing the cinematic artifice and the process of filmmaking that at times requires his own appearance in his films. Homework, Close-up, and Orderly or Disorderly are all good examples of his approach of revealing how he captures what is happening in front of his camera.

Similar to many of the French New wave films, especially those of early Godard, Kiarostami relies on natural light and seemingly unplanned camera movements that give his films a documentary look. He told me that at times he’d have many arguments with his cameraman for wanting to have long shots instead of close-ups. He also preferred a camera movement which would not end on a perfect spot. He believed that instead of perfecting the performance of his actors or his film crew he would welcome their mistakes during the shoot and would willingly include them in his films. (Similar to the way he welcomed the “misunderstanding” of the audience of his films)

Although Kiarostami pays a lot of attention to the realism in his films, he always resisted defining his films as documentary or fiction. In the beginning of Homework in response to a stranger who is asking him whether his film is a documentary or a fiction he say he doesn’t know until it is done, then he adds that it’s a visual research about homework. He did not believe in the distinction between documentary and fiction but rather in a good film versus a bad film.

Illusions

With Case No. 1, Case No. 2 Kiarostami starts to include his audience in reacting to both real and imaginary events of his film. Although I had heard about the film, it took me almost two decades to finally receive a VHS copy from Kiarostami himself . Jonathan Rosenbaum and I were trying to write a book on him and we had no access to this film. (Ever since 1992, when in Toronto International Film Festival, we both saw Where’s the Friend’s Home?, we started discussing his cinema, which resulted in writing our book together in 2003.)

What’s amazing about the film is that similar to Chronicle of a Summer (Jean Rouch, 1961), it includes its own audience (except for the school boys who act as the students) as the subject of the film. They respond to the question of the film having (apparently) viewed the fictional scenes of a troubled classroom.

The film starts with fictional piece about a teacher drawing the anatomy of a human ear on the blackboard. Every time he turns his back to the class, we hear a student making some disturbing noise. When no one wants to identify him, the teacher decides to punish a group of his students by sending them out of classroom for the whole week until they report the name of the guilty one. The second fictional piece shows one of the students who decides to betray his friends and report to the teacher the name of the guilty one and thus getting the permission to return to his classroom. These two fictional pieces apparently are shown to some of the parents as well as several authority figures, governments officials as well as educators and media people (some of whom were exiled and executed after the film) (2). They give their opinions about the situation and whether the act of the teacher or the students were right or wrong. We see the classroom scenes and assume that the interviewees have also seen them. But only the first interviewee is seen with the film projector and the film screen that shows parts of the classroom scenes. For all others, we only see the projector or hear its sound or see the film reel to help us conclude that they have all seen the classroom film.

The question of the film presented through the fictional piece evokes the emotional reaction of some of the interviewees and influences their responses. Here, not only are wev presented with the classroom situation and the opinions of the interviewees about it, but we are also confronted with the idea of cinema and its possible role in shaping people’s opinions. Interestingly, the question of the film through its voiceover is presented to both the interviewees and us as the audience of the film.

The Blurred Borders

A curious relationship between fiction and documentary forms at the end of Taste of Cherry when we cut from Mr. Badii lying in the grave to the digital video footage of him among the film crew behind the scene.

Strangely, this transition doesn’t stop our curiosity to want to see the rest of Mr. Badii’s story. The fiction builds an intimate relationship between the audience and the actor, while the video footage shows his exterior reality. Mr. Badii still looks thoughtful (just like his character in the fictional film). He is not lying in the grave but walking towards Kiarostami who is behind the camera. The surprising effect created here is mostly due to the change of format from film to the digital image while the conceptual emphasis lies on the split between acting and being.

Kiarostami shared a memory of his youth and how he wondered about acting and being while watching a Ta’zieh, (a kind of religious passion play in Shiism), in which the actor who played the horrible murderous Shemr (3) would take a break to smoke a cigarette before returning to the stage and assuming his evil mythical role.

Kiarostami entertains the idea of the shift of roles in some of his later films including Certified Copy and Like Someone in Love.

Copy/Original

I quench my thirst

by drinking from a mirage.” Abbas Kiarostami

Both films, Like Some One in Love, and Certified Copy, deal with the concepts of illusion and reality, or essence and appearance or in the director’s word, copy and the original.

They both express their hesitation and ambiguity, disbelief and disappointment in romantic relationship-a concept that emerged in earlier films such as Experience, The Report and Through the Olive Trees.

In Experience, we see a teenage boy running after a bus that carries his beloved girl who is laughing at him. In Through the Olive Trees we watch the young naïve romantic Hussein keep pursuing his beloved Tahereh who never responds to him (the extreme long shot of him following her in the vast field at the end of the film becomes the director’s statement about the eternal pursuit of the beloved.)

If Mr. Firouzkuhi is disappointed in his marriage in The Report we see an army of women in Shirin who are crying about their love life (according to Kiarostami observing them crying on and off camera).

In Like Someone in Love, the old man sets the stage for a romantic dinner in his apartment to meet a young prostitute. We find out that she is not at all interested in anything but going to bed.

Here, in the absence of the original (his daughter or wife), the old man resorts to the copy, a young prostitute. The way he treats her and his actions (cooking for her, tending her wounds, desiring her company, and protecting her against her angry boyfriend) reveal his fatherly feeling or an old illusion of romantic encounter.

What the film displays though is that in the beauty that is absent between the young woman and the lonely old man can be restored by the gorgeous cinematography of the film (especially in the driving scenes where we see the reflections of lights and sky on the car window). It seems that Kiasorstami is suggesting that what cannot be experienced in real life can be found in art and poetry, just like the Ella Fitzgerald song that fills the old man’s apartment.

Similarly, the reflections in Certified Copy generates a sense of beauty beyond the world of its characters. In the first part of the film, we watch a writer and a woman who is his hostess. They seem to have just met and have a friendly relationship. In the second half of the film we see them as married couple who argue with each other and are unhappy and hesitant about their relationship. Here, we don’t know which one to regard as original (married life) and which one to see as the copy (meeting someone new: a man or a woman) which one to see as fake and which version to consider as real and the film’s open-ending that leaves us in an ambiguous limbo, enforces these optional readings.

Kiarostami’s Vision

The rich diverse body of works of Abbas Kiarostami offer new ways of looking and interacting with cinema. With each film, he experiments with different ways of constructing and deconstructing the cinematic language.

His deceptively simple looking yet profound philosophical and insightful films with their despairing yet playfulness not only invite us to be more attentive to the world around us, but they also force us to confront with our presumptions about people and their environment and the way we are used to see them.

His films reveal different and unconventional poetic possibilities of cinema as an art form. Many film critics have compared him to Ozu (for poetic meditation on everyday life), Godard (for self-reflexivity), Rossellini (for attention to real life, human condition, use of real location, and documentary style) and Tati (for using cinematic form to create humor and social commentary), or even called him the Iranian neorealist, yet the mystery in his films demands that we formulate new ways of understanding, studying and examining his illusive cinema.

Kiarsotami at times talked about his philosophy on open-ending or arbitrary beginnings of some of his films. “Since stories begin before we encounter them and continue long after we leave them,” he said, “then it’s our choice to pick where to begin and where to end. In fact, what we are dealing is just the middle.”

He often stressed that the role of cinema is to reveal, and that the job of a filmmaker is to see and make others see.

“I have often noticed that we are not able to look at what we have in front of us, unless it’s inside a frame”, said Kiarostami.

He believed films should be authentic, that the directors have to be true to themselves.

In his last phone interview with me, he stressed this autobiographical, almost organic nature of his filmmaking. “A good film is when you reveal yourself fearlessly — without a mask, to the point of almost embarrassing yourself.”

Unlike other filmmakers who often hide behind their cameras, Kiarostami often includes himself in his films or represents himself in different ways on and off the screen. With a critical eye, he portrays his role as an urban middle-class media maker who interacts with both urban working class characters as well as impoverished villagers without patronizing them.

He also challenges his audience in different ways. With his minimalist and elliptic stories, he encourages his audience to use their imaginations and creativity to fill in what they perceive to be missing based on their expectations. Abbas Kiarostami was a multi-disciplinary artist who worked as a filmmaker, writer, poet, photographer, and video installation artist. He was one of the most prolific innovative, influential and unconventional director of our time whose rich body of work will continue to inspire the generations of filmmakers to come.

Notes:

1) Link Kiarostami and painting: Painting and cinema https://www.fandor.com/keyframe/kiarostami-ruiz-benning

2) Case No.1 Case No. 2 interviewees: The interviewees includes government officials such as Nurredin Kianoori, General Secretary of the Central Committee of Tudeh party (the communist party that soon after was banned), Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, the director of the Radio and Television of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Sadegh Khalkhali, religious magistrate of revolutionary courts, Ebrahim Yazdi( foreign minister), the Archbishop Artok Manukian, head of the Iranian Armenian Church, Rob David Shoft the religious leader of the Iranian Jewish community, a number of educational experts from Kanun, Masud Kimiai (filmmaker) ,Mahmud Enayat (writer, journalist)

(3)Shemr

Shimr ibn Ziljushan or Shimr was a son of Ziljushan from the tribe of Banu Kilab (Sunni belief differs), one of Arabia‘s Hawazinite Qaysid tribes. Shimr has a villainous reputation in Shia Islam. He is known as the man who killed Islamic prophet Muhammad‘s grandson Hussein ibn Ali at the Battle of Karbala. Shimr is depicted in the passion plays during the Shia mourning remembrance of Ashura (Day of Remembrance) in the tenth day of Muharram in the Islamic calendar in the year 61 AH (October 10, 680 CE). The massacre of Hussein with a small group of his companions and family members had a great impact on the religious conscience of Muslims, particularly Shi’a Muslims, who commemorate his death with sorrow and passion. (Wikipedia)

Ta’zieh means comfort, condolence. It comes from roots aza which means mourning. Ta’ziyeh as a kind of passion play is a kind of comprehensive indigenous form considered as being the national form of Iranian theatre which have pervasive influence in the Iranian works of drama and play. (Wikipedia)