From the January 17, 2003 issue of the Chicago Reader. For those who care about such things, there are spoilers ahead. — J.R.

25th Hour

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Spike Lee

Written by David Benioff

With Edward Norton, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Barry Pepper, Rosario Dawson, Anna Paquin, Brian Cox, Tony Siragusa, and Levani.

I’ve complained a lot about Spike Lee as a filmmaker, before he made his remarkable Do the Right Thing (1989) and after. But the only time I’ve been tempted to accuse him of falling back on the tried and true was when he made Malcolm X and attempted to adapt his subject’s autobiography as if he were Cecil B. De Mille or David O. Selznick. I don’t mean that Lee hasn’t stubbornly stuck to the same stylistic tropes and mannerisms throughout most of his career — leaving them behind only when the occasion demanded it, as in his expert filming of Roger Guenveur Smith’s powerful performance piece The Huey P. Newton Story — but the stylistic consistency is his own. Moreover, taking on dissimilar projects he has always moved in exploratory directions, showing a lot of courage and initiative in his creative choices — even when they’re half-baked (as some are in Get on the Bus) or overblown (as in Bamboozled). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 18, 2003). — J.R.

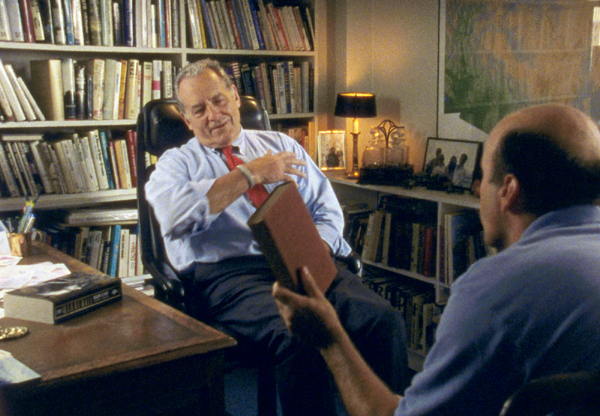

Stone Reader

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Mark Moskowitz.

Cinema has traditionally been regarded as the art that encompasses all the other arts. But start considering how successfully cinema encompasses any particular art form and the premise falls apart.

Filmed theater, opera, ballet, and musical performance omit the existential and communal links between performer and audience that their live equivalents rely on. Paintings can be filmed, but films that allow us even some of the freedom viewers have in galleries, museums, and other public and private spaces are rare enough to seem like aberrations. Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s 1989 Cézanne [see above] — which has the nerve to give us extended views of C

From the January 17, 2003 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

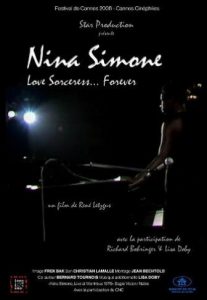

Rene Letzgus’ 1998 French documentary of a 1976 concert is hampered by a few distractions such as shots from inside a car cruising through Paris and actor Richard Bohringer in a studio muttering comments in unsubtitled French. (To all appearances these intrusions are simply efforts to paper over gaps in the visual continuity.) But the event being documented is so riveting and so eccentric in its own right that the interruptions hardly matter. The only time I’ve seen Simone live was when she sang “Mississippi Goddam” on the last lap of the Selma-Montgomery march, and although she doesn’t reprise that fiery anthem here, she’s just as unforgettable. This isn’t so much a concert as a work of performance art — one of the best I’ve seen since Richard Pryor–Live in Concert — in which Simone’s divalike behavior is as much a part of the show as her Juilliard-trained piano playing and her stupendous untrained voice. Whether she’s performing “Little Girl Blue” and a Langston Hughes tribute, alternately barking at or complimenting the audience (or getting them to sing with — or instead of — her), making cryptic comments to herself about show business or life in general, or dancing in high heels to African drums (when she isn’t simply listening to them, or adding a piano riff), she’s such a commanding and powerful presence that I was mesmerized for most of the film’s 75 minutes. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 28, 2003). — J.R.

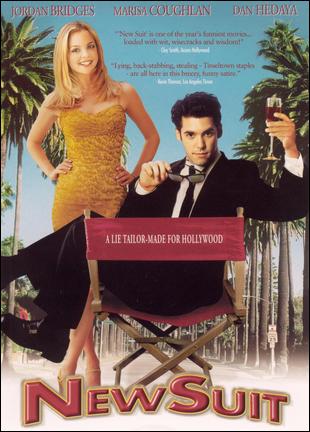

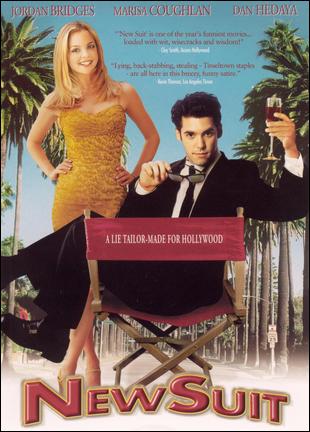

New Suit

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Francois Velle

Written by Craig Sherman

With Jordan Bridges, Marisa Coughlan, Heather Donahue, Dan Hedaya, Mark Setlock, Benito Martinez, Charles Rocket, and Paul McCrane.

As the opening narration makes clear, New Suit — a satirical comedy about Hollywood suits — is loosely based on “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Kevin Taylor, a 24-year-old script editor and frustrated screenwriter, is already jaded after 18 months working in the office of has-been producer Muster Hansau. Taylor (Jordan Bridges) gets especially irritated one day after hearing some of his hotshot coworkers spout bullshit at the studio commissary. He gets up from the table and buys a strawberry ice cream cone from a guy named Jordan, then returns and starts talking about an imaginary hot new script called “New Suit” by an imaginary writer named Jordan Strawberry that he says his bosses are excitedly pursuing.

His tablemates simultaneously claim they’ve already heard about the script and pump him for more information. Before long the whole town is talking about this promising property — especially after Kevin’s former girlfriend Marianne, a rising agent, overhears him saying that Strawberry is “unrepresented.” She promptly claims to be representing him, which starts a bidding war between two studios. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 11, 2003). — J.R.

10

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Abbas Kiarostami

With Mania Akbari, Amin Maher, Roya Arabshahi, Katayoun Taleidzadeh, Mandana Sharbaf, Amene Moradi, and Kamran Adl.

In my mind, there isn’t as much of a distinction between documentary and fiction as there is between a good movie and a bad one. — Abbas Kiarostami in an interview

One way to identify the world’s greatest filmmakers is to determine which ones have found it necessary to reinvent the cinema from the ground up. The names that quickly come to my mind are Antonioni, Bresson, Chaplin, Dreyer, Eisenstein, Godard, Griffith, Kubrick, Mizoguchi, Renoir, Tati, and Welles — a far from exhaustive list of mercurial artists who rethought the nature of the medium not once but repeatedly, most often to their commercial disadvantage.

Not all of these figures qualify as “difficult,” though even such crowd pleasers as Chaplin, Griffith, and Kubrick were called that at some points during their careers. Whether people wound up seeing them as old-fashioned or unfashionable, these artists refused to turn themselves into commodities, alienating even their most passionate fans by confounding expectations and changing the rules of the game, and at times scaring off potential investors. Read more

From the April 25, 2003 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

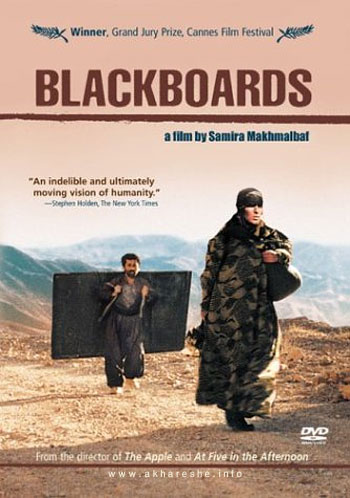

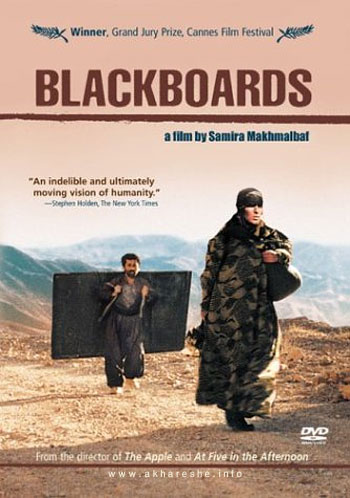

Blackboards

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Samira Makhmalbaf

Written by Mohsen and Samira Makhmalbaf

With Bahman Ghobadi, Said Mohamadi, and Behnaz Jafari.

I don’t know why it’s taken three years for Samira Makhmalbaf’s second feature to reach Chicago. It was finished in 1999 and won the jury prize at Cannes the following year. The Iranian director was only 17 when she finished her remarkable first feature, The Apple, which also screened in competition at Cannes and made her one of the youngest directors ever to gain an international reputation. Since then, she has made the 11-minute “God, Construction and Destruction,” about the responses of Afghan refugee children in Iran to the attacks on the World Trade Center, which is part of the 2002 international episodic feature 11/09/01 (still unscreened in the U.S.). She has also made the feature At Five in the Afternoon, about a young woman in post-Taliban Afghanistan, which is expected to premiere at Cannes in May.

All of her features to date have been produced, edited, and written or cowritten by her father, Mohsen Makhmalbaf. But the three films of hers that I’ve seen are significantly different from his in that they deal with communities more than individuals, and I happen to like The Apple more in some respects than any film directed by him. Read more