Part of a roundtable discussion with David Edelstein, Roger Ebert, Sarah Kerr, and A.O. Scott in Slate, December 26, 2001. Sorry that I can’t furnish the post from David that led to it. Note: let your cursor hit the first illustration below. — J. R.

Dear David (and Roger, Sarah, and Tony),

I appreciate your evocation of Sept. 11 at the start of your letter — a defining moment for us all — as well as your conflicted thoughts about vigilantism, and how these impact on your movie tastes. For me, there’s no conflict of this kind, because I’m afraid revenge strikes me as something less than an adult aspiration or concern — accounting both for why I think Mandela’s South Africa is far ahead of the United States in this respect and why In the Bedroom, a very well-made film, doesn’t interest me much. (The only moment I recall making my pulse race was when Spacek slapped Tomei.) As you’re the first to point out, Osama Bin Laden is also obsessed with vengeance — though surely not just for “slights against his brand of Islam.” Other beefs might include the deaths of about a million innocent Iraqis (the American Friends Service Committee’s estimate last spring) — collateral damage that Madeleine Albright told us she had no regrets about, despite the fact that it arguably only strengthened Saddam Hussein — as well as many other lethal forms of meddling in the Middle East, some of them slights against both humanity and common sense.

Read more

One of my “En movimiento”columns for Cahiers du Cinéma España, written specifically for their special Godard issue (December 2010). — J.R.

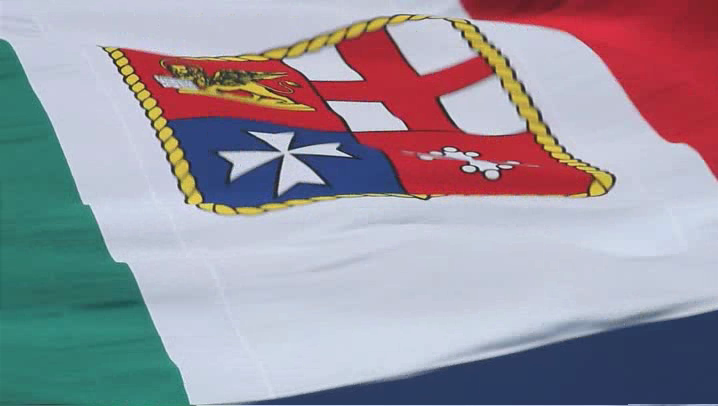

Writing recently here about the largely negative American reception of Film Socialisme at Cannes, I noted — in response to the implications of such critics as Todd McCarthy and Roger Ebert that the film’s difficulties could somehow be attributed to flaws in Godard’s character — that I was “impressed not only by the film’s singular, daring, and often beautiful employments of sound and image, but also by its tenderness towards virtually all the contemporary characters and figures in the film (including the animals) — a virtue I don’t find at all present in For Ever Mozart.”

One could, in fact, go through many portions of Godard’s filmography and cite works that are humanist (such as Bande à part, Masculin-Féminin, and France/tour/detour/deux enfants) and those that are relatively nonhumanist (such as Weekend, Vladimir et Rosa, and Passion). Even though one could argue that Godard’s self-imposed social isolation since his departure from Paris has had harmful effects on his art, it is too simplistic to assume that he’s always or invariably the simple grouch that many journalists have claimed him to be. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 500). I can think of two plausible reasons for reposting this now: Raquel Welch and Babylon.

I’m not sure why I neglected to mention Fatty Arbuckle, but obviously I should have. (I also might have mentioned that another long narrative poem by Joseph Moncure March, The Set-Up, provided the basis for a more enduring 1949 Robert Ryan/Robert Wise feature.)– J.R.

U.S.A., 1974

Director: James Ivory

Cert–X. dist–7 Keys. p.c–The Wild Party.A Samuel Z. Arkoff presentation. exec. p–Edgar Lansbury, Joseph Beruh. p-Ismai Merchant. assoc. p—George Manasse.asst. d–Edward Folger. sc–Walter Marks. Based on the narrative poem by Joseph Moncure March. ph–Walter Lassally. col–Movielab. ed–Kent McKinney. a.d–David Nichols. set dec–Bruce David Weintraub. set artist–Pamela Gray. sp. effects–Edward Bash. m/m.d–Larry Rosenthal. dance m–Louis St. Louis. songs–“Wild Partv”, “Funny Man”, “Not That Queenie of Mine”, “Singapore Sally”, “Herbert Hoover Drag”, “Ain’t Nothing Bad About Feeling Good”, “Sunday Morning Blues” by Walter Marks. musical sequences staged by–Patricia Birch. cost–Ron Talsky, Ralph Lauren, Ronald Kolddzie. make-up-Louis Lane. titles— Arthur Eckstein. title poster art–Peter Diaferia. sd. ed–Mary Brown. sd. Read more

The following article was written for the June 8, 2001 issue of the Chicago Reader, to coincide with the release of Jafar Panahi’s The Circle in Chicago — although a differently edited version was published. This is my original version, which I included in Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia, a 2003 collection I coedited with Adrian Martin. (Lamentably but unsurprisingly, this was the only section of the book that was left out of the Persian translation.)

One indication of Panahi’s extraordinary courage, after his appalling incarceration in Tehran’s Evin prison back in March, was the fact that he expressly requested not to be accorded “special” treatment because of his status as an artist and filmmaker. It seemed worth reposting this article on December 21, 2010, not only because of the shocking sentence received by Panahi after his trial, but also to correct the original misdating of this article on this site and in Movie Murtations, which I learned about via David Bordwell’s site. — J.R.

Squaring The Circle

Last month, I was taken aback by an email from a colleague — not a cranky stranger — waiting for me at my office computer one morning. Read more

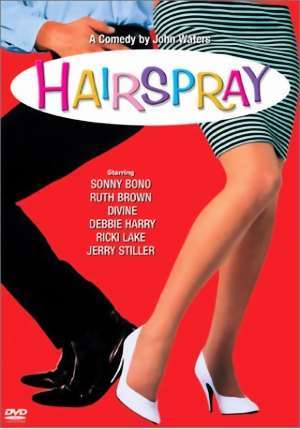

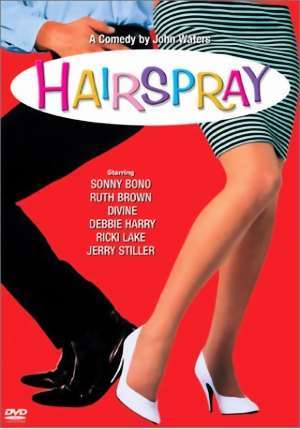

This is a review of the John Waters original (1988) — not the Adam Shankman remake (2007) derived from the Broadway musical, which I haven’t seen. Thanks to the seeming omnipresence of the latter, I originally found it very difficult to find any stills from the former on the Internet. My review appeared in the March 4, 1988 issue of the Chicago Reader. Today I persist in thinking that America would be a better place if John Waters were hosting The Tonight Show. — J.R.

HAIRSPRAY

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by John Waters

With Ricki Lake, Divine, Leslie Ann Powers, Colleen Fitzpatrick, Ruth Brown, Sonny Bono, Debbie Harry, and Shawn Thompson.

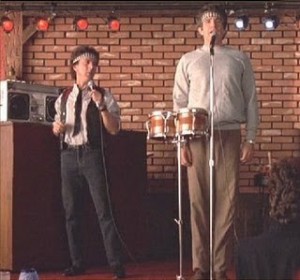

As John Waters is the first to point out, Hairspray is “a satire of the two most dreaded film genres today — the ‘teen flick’ and the ‘message movie.'” But one of the nicest things about this exhilarating, good-natured pop comedy is that it actually is both a teen flick and a message movie. Satirical or not, it redeems as well as revitalizes both genres while celebrating their excesses.

This downscale, urban Dirty Dancing is a cunning crossover maneuver that opens as many doors to the mainstream audience as Waters can reach for, urging black and white, fat and skinny, blue collar and white collar, and generations some 25 years apart to join in the festive euphoria. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, June 18, 1993. (This is also reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics.) — J.R.

Who is correct? Are we becoming better off or worse off? Where are we heading? It depends on whom you mean by “we.” — Robert B. Reich, The Work of Nations

“Men never get this movie,” a woman says to her friend in Nora Ephron’s Sleepless in Seattle, referring to Leo McCarey’s 1957 An Affair to Remember, with Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr, which is showing on TV. In fact, we’re told this again and again. Another woman tearfully describes the last scene of An Affair to Remember to the hero, who remarks, “That’s a chick’s movie.” To clinch the point, female characters in this romantic comedy are repeatedly shown watching this movie and sobbing (as if the TV stations in Seattle and Baltimore, where most of the action takes place, showed little else), and men are never seen watching it at all. And just in case we’re left with any doubts about the matter, the review of Sleepless in Seattle in Variety assures us that An Affair to Remember‘s “squishy romantic elements appeal to women more than men.” Read more

This interview with Han Jian, reporter for the Bund Pictorial– a culture and lifestyle weekly based in Shanghai — was conducted for a cover story about American film critics planned for their February 17, 2015 issue. [Feb. 28: Now that I’ve been sent a link, it’s clear that the Chinese version of this piece is somewhat longer, because of an added introduction.]– J.R.

1. How did you become a film critic? Do you still remember your first film review?

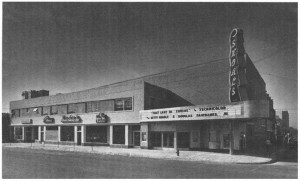

Much of this is described in my first book, an experimental memoir entitled Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980; second edition, 1995). I was the grandson and son of movie theater exhibitors in northwestern Alabama, which enabled me to grow up watching a great many movies for free. My father wrote a column for the local newspaper promoting the current releases, and shortly after my 14th birthday, I substituted for him one week, although this wasn’t actually a review. But the following year, I published my first actual film reviews — of The Astounding She-Monster, The Viking Women and the Sea Serpent, The Vikings, and a live TV drama called No Place to Run — in my high school newspaper. Read more

From the February 2014 Artforum; their title was “Beyond Good and Evil”. — J.R.

Claude Lanzmann, The Last of the Unjust, 2013, 16 mm and 35 mm, color and black-and-white, sound, 218 minutes. Claude Lanzmann and Benjamin Murmelstein.

THE LAST OF THE UNJUST, the latest of Claude Lanzmann’s footnotes and afterthoughts to his 1985 masterpiece, Shoah, functions even more than that earlier film as a dialectical palimpsest, so its successive layers — which remain in perpetual dialogue with one another — should be identified at the outset:

December 1944: Benjamin Murmelstein, a Vienna rabbi, is appointed by the Nazis as the third (and last) Jewish “elder” of Theresienstadt (Terezin, in Czech), a “model” or “showcase” ghetto set up in the former Czech Republic in 1941, his two predecessors having been executed the previous May and September. Murmelstein retains this position through the war’s end. Then, after spending eighteen months in prison for his collaboration with the Nazis, he is acquitted of all charges (although still widely despised as a traitor) and moves to Rome.

1961: Murmelstein publishes a book in Italian, Terezin: Il ghetto-modello di Eichmann, describing the suffering of the ghetto’s inhabitants.

1975: Lanzmann films an interview with Murmelstein over a week in Rome — the first interview that he films for Shoah, although he later decides to discard it, donating the unedited footage to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 10, 1993). — J.R.

The most impressive thing about Steven Soderbergh’s third feature (after sex, lies, and videotape and Kakfa) — an adaptation of A.E. Hotchner’s childhood memoirs, rich in period flavor — is that it’s set in Saint Louis in 1933, roughly three decades before Soderbergh was born, yet it offers a pungent and wholly believable portrait of what living through the Depression was like. Soderbergh gets an uncommonly good lead performance out of Jesse Bradford as the resourceful 12-year-old hero, living in a seedy hotel and steadily losing the members of his family: his kid brother (Cameron Boyd) gets shipped off to an uncle, his mother (Lisa Eichhorn) to a sanitarium, and then his German father (Jeroen Krabbe) goes off to try to make money as a door-to-door watch salesman. We also learn a fair amount about the hero’s neighbors (Spalding Gray, Elizabeth McGovern, Adrien Brody) and schoolmates, and Soderbergh does a fine job of keeping us interested and engaged without stooping to sentimentality. This is a lovely piece of work. Fine Arts.

Read more

Read more

The second part (roughly the second half) of Chapter One of my most popular book, Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000); for the first half, go here. The illustration below is from the now out-of -print English edition. — J.R.

Is the Cinema Really Dead?

Susan Sontag’s essay “A Century of Cinema” — a generational lament whose validity for me both rests on and is partially thrown into doubt by its generational stance — has by now appeared in many languages around the world as well as in many different English-language publications, including the The New York Times Magazine (February 25, 1996), the “movie issue” of Parnassus: Poetry in Review (volume 22, nos. 1 & 2, 1997), The Guardian, and at least two book-length collections of essays. I’ve noted many interesting variations in this piece as it’s appeared in various settings, and assume that some of these represent subsequent revisions or afterthoughts on Sontag’s part. But the most striking differences appear between the first version published in America — in The New York Times Magazine, with the strikingly different title “The Decay of Cinema” — and all the others, and I assume that these, including the title, stem from editorial interventions, or at the very least collaborations between Sontag and her editor or editors at the Times. Read more

From Chris Fujiwara’s 800-page collection Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007).

I’ve just read an advance copy of a terrific new book about this film by Nick Pinkerton, endlessly informative and packed with ideas. Don’t miss it! Fireflies Press is publishing it.– J.R.

Scene

2003 / Goodbye, Dragon Inn – The shot of the empty auditorium near the end.

Taiwan. Director: Ming-liang Tsai. Original title: Bu san.

Why it’s Key: A minimalist master shows what can be done with an empty movie-theater auditorium.

One singular aspect of Ming-liang Tsai’s masterpiece is how well it plays. I’ve seen it twice with a packed film-festival audience, and both times, during a shot of an empty cinema auditorium, where nothing happens for over two minutes, you could hear a pin drop. Tsai makes it a climactic epic moment.

Indeed, for all its minimalism, Goodbye, Dragon Inn fulfills many agendas. It’s a failed heterosexual love story, a gay cruising saga, a Taiwanese Last Picture Show, a creepy ghost story, a melancholy tone poem, and a wry comedy. A cavernous Taipei movie palace on its last legs is showing King Hu’s 1966 hit Dragon Inn to a tiny audience — including a couple of the film’s stars, who linger like ghosts after everyone else has left — while a rainstorm rages outside. Read more

From Moving Image Source (www.movingimagesource.us), posted September 22, 2009. Also reprinted in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

Following James Agee: Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005), and American Movie Critics (2006), Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber is the Library of America’s third and so far most ambitious effort to canonize American film criticism — a daunting task that’s been lined at every stage with booby traps, at least if one considers the degree to which film criticism might be regarded as one of the most ephemeral of literary genres. And this is certainly the volume that adds the most to what has previously been available; by rough estimate, it easily triples the amount of film criticism by Manny Farber that we have between book covers.

As Karl Marx once pointed out, quantity changes quality, but this doesn’t entail any lessening of Farber’s importance. I would even argue that both the nature and evolution of his taste and writing over 30-odd years, before he gave up criticism to concentrate on his painting, still make him the most remarkable figure American film criticism has ever had.

Bringing a painter’s eye to film criticism and couching even his most serious observations in a snappy, slangy prose, Farber was the first American in his profession to write perceptively about the personal styles of directors and actors without any consumerist agendas or academic demonstrations. Read more

The first part (roughly the first half) of Chapter One of my most popular book, Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000). The second half will be posted tomorrow; the illustration below is from the now out-of-print English edition. — J.R.

Is the Cinema Really Dead?

[The] early nineties have not been as encouraging as the early seventies.. . . It is not as easy now to believe in the medium’s vitality or its readiness for great challenges. So many of the noble figures of film history aredead now, and who can be confident that they are being replaced? . . . .The author sees fewer films now. He would as soon go for a walk, look at paintings, or take in a ball game. [1994]

It has become harder, this past year, to go back in the dark with hope or purpose. The place where “magic” is supposed to occur has seemed a lifeless pit of torn velour, garish anonymity, and floors sticky from spilled sodas. Forlornness hangs in the air like damp; things are so desolate, you could set today’s version of Waiting for Godot in the stale, archaic sadness of a movie theater. Read more

My column for the Summer 2016 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

J.P. Sniadecki’s feature-length The Iron Ministry (2014), available on DVD from Icarus Films, is by far the best non-Chinese documentary I’ve seen about contemporary mainland China. (Just for the record, the best Chinese documentary on the same general subject that I’ve seen is Yu-Shen Su’s far more unorthodox—and woefully still unavailable — 2012 Man Made Place; a couple of snippets are available on YouTube and Vimeo.) Filmed over three years on Chinese trains, it’s full of revelatory moments, and not only in its surprisingly outspoken interviews: the non-narrative stretches, which compare quite favourably with the more abstract portions of Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s Leviathan (2012), are pretty stunning as well. Skip this one at your peril.

Second Run’s very first Blu-ray — Pedro Costa’s Horse Money (2015) — is gorgeously transferred, and has splendid extras: Costa’s 2010 short film O nosso homem, essays by Jonathan Romney and Chris Fujiwara, an introduction to Horse Money’s introduction by Thom Andersen, and Laura Mulvey’s conversation with Costa at London’s ICA. The extras on Criterion’s Blu-ray of Jean-Luc Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964) are too numerous to mention here, but suffice it to say that just about every intertextual reference in this cherished object are teased out in one way or another. Read more

From Cinema Scope (Spring 2005, issue 22). The down side of reproducing my old DVD columns is that many of the links are bound to be out of date and no longer functional; the up side is that they offer some kind of history of what used to be available (or unavailable). — J.R.

With the exception of a few film buffs at some of the more discerning labels, and still fewer at the major studios, decisions about what older films to release on DVD, as well as when or why, are often capricious to the point of absurdity. So asking why some things are readily available and some things aren’t is a bit like asking an illiterate about his or her reading taste. Some time ago, I was contacted about contributing to the extras of an ambitious DVD being planned for Elaine May’s infamous and underappreciated Ishtar — a project developed with loving care by some maverick film buffs at Columbia/Tristar over many months, eventually soliciting the unprecedented cooperation and input of May herself.

It seemed like a golden opportunity for some thoughtful studio revisionism — especially in light of how much this prescient farce has to say about the dangerous blunders of American innocence and stupidity in the Middle East and how blind American reviewers were to this aspect of the movie back in 1987. Read more