From the Chicago Reader, June 18, 1993. (This is also reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics.) — J.R.

Who is correct? Are we becoming better off or worse off? Where are we heading? It depends on whom you mean by “we.” — Robert B. Reich, The Work of Nations

“Men never get this movie,” a woman says to her friend in Nora Ephron’s Sleepless in Seattle, referring to Leo McCarey’s 1957 An Affair to Remember, with Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr, which is showing on TV. In fact, we’re told this again and again. Another woman tearfully describes the last scene of An Affair to Remember to the hero, who remarks, “That’s a chick’s movie.” To clinch the point, female characters in this romantic comedy are repeatedly shown watching this movie and sobbing (as if the TV stations in Seattle and Baltimore, where most of the action takes place, showed little else), and men are never seen watching it at all. And just in case we’re left with any doubts about the matter, the review of Sleepless in Seattle in Variety assures us that An Affair to Remember‘s “squishy romantic elements appeal to women more than men.”

This is utter nonsense. Since the time of the movie’s first release, when I was 14, I’ve seen this movie countless times, and I’m incapable of getting through it without crying. I have plenty of male friends who love it too — more of them, as it happens, than female friends. In fact, when I went to see the movie with a highly emotional English girlfriend in Paris 20 years ago, I was in tears at the end and her eyes were completely dry; she thought it was a hoot.

Moreover, during the movie’s initial release, you could see An Affair to Remember in CinemaScope — as you could at the Chicago Film Festival’s CinemaScope retrospective a couple of years back, and as you probably still can in Paris today. In Sleepless in Seattle you can catch only “scanned” clips of it on various TV sets, with about a third of the image removed from both sides of the frame. Some marketing executives decided many years ago that we all preferred to see films that way on TV, without the benefit of McCarey’s exquisitely composed and measured framing; they assumed it was better to eliminate a third of the image than to use a letterboxed format. Properly speaking, a better title for the movie as it now appears in Sleepless in Seattle would be An Affair to Remember Piecemeal.

There are two kinds of misjudgment (and abridgment) going on here — demographic and aesthetic — and they seem to go together, because they’re both dictated by unreflecting and ahistorical marketplace thinking. This kind of thinking now determines many of the ways we experience movies; it tells us what we’re supposed to like and implies that we’re not being cooperative — not behaving like happy campers — if we happen to disagree.

It’s theoretically possible, of course, that producers and marketing “experts” at 20th Century-Fox back in 1957 decided, long before Nora Ephron, that An Affair to Remember was to some extent a “woman’s picture.” But even if they did, it’s important to bear in mind that a division of labor still existed then between creative people and salespeople: regardless of what the producers thought and regardless of what the ads said, McCarey could still turn out a movie that could make someone like me cry. Today, when demographic thinking exerts a much greater influence on screenwriting and directing, as I’m sure it did on Sleepless in Seattle, the chance of someone like me being reduced to tears is much lower. And if I wanted to explain why I wept at McCarey’s movie in Paris 20 years ago while my former girlfriend laughed, I wouldn’t try to delve into what was wrong with me or with her; I’d try to discuss what was right about An Affair to Remember — irrespective of what marketing executives thought then or now.

Targeting has been part of our cultural life for some time, but it has become so prominent over the past few years that I think it’s making a mess of the way we live and think and relate to one another. When businesses treat us demographically, as simply parts of vast marketing units, we eventually start thinking of ourselves in the same way — with the frequent result that whatever confounds, contradicts, or challenges these calculations gets factored out of art, communication, and even what we regard as our own identities. (Either these elements are eliminated at the outset or, if they’re left in, we’re encouraged not to notice them.) And when marketing executives start molding not only our tastes but our own self-definitions, it’s time to start wondering who is serving whom and why.

It would be wrong, I think, to place all of the blame for this state of affairs on the film industry. Out in the “real” world, where competing interest groups clamor for “politically correct” representations of their identities and concerns, what these identities and concerns actually consist of often is reduced and oversimplified for practical reasons. Just as some men cry at so-called women’s pictures, some women may feel that their political interests can be represented by men, even if it isn’t always politically efficacious to say so. Unfortunately, what gets said is assumed to be what “women want.” The same thing applies, of course, to whites who feel that blacks can represent them (or the reverse). As one woman writer pointed out to me recently — to cite one of the many disparate casualties of PC discourse — it’s become very hard nowadays to even think of criticizing mothers or motherhood.

Consequently, whenever we hear about “women’s” interests, “black” interests, or “gay” interests — and we hear about them much more than we hear about “men’s” interests, “white” interests, or “straight” interests only because the latter are already firmly entrenched — we’re usually asked to assume that these are homogeneous, coherent entities. The assumption behind these shorthand formulas — which are becoming increasingly institutionalized throughout our culture — seems to be that all women, all blacks, and all gays have the same interests, just as all men, all whites, and all straights are presumed to have the same interests. (For the record, Ephron indirectly mocks this notion in Sleepless in Seattle when she has a male character describe how he cried during the last scene of The Dirty Dozen — perhaps the only display of wit in the entire movie.)

However these assumptions may (or may not) apply to legislation or short-term business investments, they often play havoc with how we perceive ourselves as human beings. After all, no one is ever any one of these categories to the exclusion of all others. And whatever’s left out of these calculations simply isn’t being addressed.

All these impoverished definitions of who we are wind up operating as negative or oppositional descriptions, sometimes even in spite of the intentions of whoever utters them. Regardless of what Robert Reich means in his book The Work of Nations, it’s entirely possible to conclude from his arguments, given the divisions currently built into our discourse, that we should be ecstatically happy about our future in the world economy if we’re well educated, despairing to the point of suicide if we’re not; and I guess if we’re unlucky enough to be homeless, we’re probably not reading his book anyway. Demographically speaking, this gives us three scintillating choices of how to feel about ourselves in relation to the present global economy: selfish, defeated, or off the graph entirely.

Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far away, movies were supposed to be for everyone — made that way and seen that way — and were therefore social events that involved a diversified community. Some of this universality was undoubtedly mythical, but another part was surely real — and accounts for the continuing appeal of such certified popular classics as King Kong, Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, and Casablanca, not to mention An Affair to Remember. But movies today, even when they cite such models as exemplary, as touchstones, almost invariably intensify the distances between us instead of speaking to our common situation. They are designed to splinter and isolate us from one another, not draw us together. Apparently someone figured out that more money could be made that way.

A playwright friend of mine says there are two ways you can look at plays and movies — as windows or as mirrors — and for some time now, at least since the early Reagan years, mirrors have been the only thing we’re supposed to want. This has a direct bearing on the way films get programmed, exhibited, and promoted, and has an even more insidious effect on the way they’re conceived and made — or not made in many more cases. It affects the independent sector every bit as much as the mainstream, perhaps more so: how else to explain the relatively recent growth of film festivals devoted to films by and about women, blacks, and gays — films whose feminism, blackness, or gayness is automatically assumed to supersede their other qualities? The fact that these mirrors are supposed to be mainly flattering limits the options of filmmakers and audiences even further. (Sometimes, to be sure, the same movie can function as both window and mirror — Menace II Society presumably serves as both a window for middle-class audiences looking at ghetto horrors and as a mirror for certain blacks in ghettos. But in this case it might be argued that both audiences are insulted to some extent by the degree of sensationalism and violence thought necessary to engage their interest in this subject. And in What’s Love Got to Do With It, another combined window and mirror, everybody gets to look at wife beating, but no one gets to see Tina Turner relating sexually to a white man.)

We’re all being repeatedly assured — not least by the discourse about “correct” representations that surrounds us — that, regardless of who we are, we all go to movies chiefly in search of role models, positive images of ourselves. (Feminists who might object to my formulation, pointing out that misogyny is given unbridled play in contemporary movies, should consider that they may be considered demographically less important than misogynists.) According to this rule, I should be on the lookout for movies that project positive images of straight, middle-aged, southern-born male Jews — though the only fairly recent example that springs to mind, Driving Miss Daisy, makes me more than slightly ill. Clearly I’m being irresponsible by not living up to my demographic duties, but I’m not inclined to feel apologetic. The truth is, I prefer windows to mirrors.

I admit that the reasons for this may be partly generational, partly circumstantial. Growing up Jewish in a southern town during the 50s undoubtedly made me — along with my playwright friend, who grew up as a French Protestant during the same period in Cuba — something of a xenophile, with a desire to project myself into cultures, ethnicities, and life-styles other than my own. The common and defeatist supposition that most Americans are xenophobic by nature rather than because of their culture and education is so seldom challenged that any deviations from this profile tend to be rejected before they’re even considered. (For an interesting alternative view, check out Clive James on the subject of Mark Twain in the June 14 issue of the New Yorker.)

My own belief, for whatever it’s worth, is that the reliance of recent movies on tried-and-true xenophobia and tribal self-glorification — which often amount to right and left variations on the same narrow marketthink — is largely predicated on an absence of imagination, courage, inclination to develop fresh markets, or ability to understand what audiences are open to. These absences may not matter to multinationals that couldn’t care less about where their money’s coming from, but they’re depressing to just about anyone who cares about movies.

In terms of short-term gains, the logic of these companies’ lack of concern may seem impeccable, but the tendency of this policy to waste genres and cycles as well as sensibilities recalls the scorched-earth policy of Reaganomics — use up whatever resources you have now and don’t worry about next year’s crop. If you believe the industry analysts, there’s simply no way out of this sterile recycling of old ideas and compulsive remakes and sequels; so much for the alleged freedom of open minds and markets.

If we accept this prognosis, there’s no point in going to movies any longer — not if we’re looking for fanciful windows like An Affair to Remember instead of flattering mirrors like Sleepless in Seattle. This is not to say I don’t believe in identifying with characters in movies, or even with movies inside of other movies. (If Ephron’s film showed she had even a clue as to why McCarey’s movie makes anyone cry, her elaborate exercise in piety might have seemed worth it.) But the fact that I find it easier to empathize with the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park than with any of the human beings probably stems from the fact that, as far as the movie’s calculations about my profile as a viewer are concerned, I’m as much of a clone as any of them. Like those Disney-fied prehistoric animals — alternately stuffed toys and predatory beasts — I’m waiting for all the high-tech computer systems in the control station to shut down so I can run free for a spell, even if that means causing some damage. I want to be liberated from the itinerary this theme-park ride has mapped out for me. It assumes that I’ll be delighted to see greedy ersatz characters get their just desserts and accept the movie’s moralism about tampering with nature for profit — which I’m expected to associate only with the designated villains, not with Spielberg and company.

More than anything else, what has destroyed the possibility of good or even coherent studio pictures getting made in recent years has been test-marketing previews. I recently learned that it was thanks to this practice that Joe Dante’s The ‘Burbs wound up with a stupid ending that contradicts the clever preceding premises and that Dante disapproves of. [February 2010 postscript: I later found out that Dante actually wanted this ending.] The movie flopped anyway, so everyone lost out — a turn of events I’d wager happens much more often than most studio executives would care to admit. Perhaps irrationally, I’m still hankering after the volcano climax that once ended Sliver (which, after the strong opening weekend the targeters were aiming for, has been deservedly plummeting at the box office), if only because it implied a form of dementia much more entertaining than what replaced it after the test previews. For all the satisfaction of Sharon Stone’s closing line in the release version — “Get a life!” — one is still prompted to bark back at the screen, “Get a movie!”

Obviously, desperate, last-minute second-guessing of this kind is likelier to produce gibberish than anything promised by the ads. Because very few spectators, including those at test previews, are prone to analyze or think much about what they’re watching on the spot, putting their collective twitches into the auteur’s seat makes about as much sense as sculpting our foreign policy around the public’s gut reactions to TV news reports. (People are at their most reactionary when they’re least prone to be thinking, something marketing experts bank on.) This strategy doesn’t allow for second thoughts — for the sort of response that might come an hour or a day after leaving the theater — or for fidelity to any long-range educated strategies or reasoned deliberations that might have preceded the market tests. Everything is tossed out for the sake of that opening weekend, with the often empty assurance that restoring the “original director’s cut” (whatever that is) on laserdisc will make everything all right again.

I’ve seen three movies recently in which an arrogant male chauvinist character plays a central role — a crime writer (Tom Berenger) in Sliver, an upper-class gigolo (Don Johnson, the best performance of his I ever hope to see) in Guilty as Sin, and an art critic (Robin Renucci) in a French film from 1985 by Jean-Charles Tacchella, Stairway C (showing this Saturday at Facets Multimedia). All three movies threaten to show us a sympathetic female character who’s sexually attracted to the male chauvinist. Not surprisingly, the French movie meets this challenge head-on, without flinching, while the two American movies devise various excuses for backing away from it — in both cases to their detriment as thrillers exploring certain moral tensions. (Stairway C, I should hasten to add, isn’t a thriller, and its implications are quite different.) We all know women who are turned on by male chauvinists, but the chances of encountering this phenomenon in a “major studio release” are lessened by the offense it would likely bring to certain members of the audience (myself, no doubt, included).

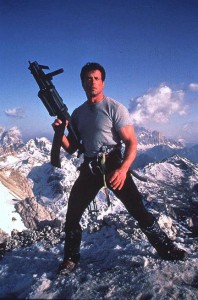

This example of studios making decisions about a movie’s content based on “political correctness” is a minor one — the everyday sort of simplification that’s currently expected from movie mirrors. A more grotesque example of the same tendency can be found in the determination of Cliffhanger to cast blacks and women in positive as well as negative roles and as victims as well as nonvictims, despite the fact that the movie’s modus operandi throughout is to treat its audience as a callous mob howling for blood. This places women and blacks in politically correct roles at the same time that it allows misogynists and racists to satisfy their blood lust: democracy at work. Thanks to careful targeting, neither xenophobes nor tribal narcissists should have any cause for complaint; it’s only all the rest of us — a negligible pack of humanists, xenophiles, and various others missing from the charts — who’ve been left out in the cold.