This appeared in The Soho News (August 18, 1981). Apologies for the stupid headline; my editor at the time was addicted to bad puns of this kind.– J.R.

An Enemy of the People

Directed by George Schaefer

Public Theater

Beatlemania — The Movie

Directed by Joe Manduke

A cherished personal project of Steve McQueen, who served as executive producer as well as lead actor, Henrik lbsen’s An Enemy of the People, scripted by Alexander Jacobs, is a lot more appealing and less forbidding than its cultural aura might suggest. That McQueen was unable to get this 1977 film released prior to his death is unfortunate yet unsurprising; given the absence of outlets for movies of this kind in the United States, I would have thought that cable might prove to be its ideal resting place. But at least for us Manhattan country folk, it’s once again thanks to the underappreciated services of the Public Theater that we’re able to see it at all.

McQueen made this movie when he knew that he was dying of cancer and decided that he wanted to be remembered for something more than his blue-eyed beefcake parts. An advocate of Laetrile cancer therapy -– banned by the FDA, and usually pegged as “controversial” in this country – McQueen had to go to a Mexican clinic to get the treatment he wanted and must have had plenty of reasons to identify with Ibsen’s persecuted, innocent, and idealistic hero. An Enemy of the People isn’t a major or important film, but it’s at least as good as any other McQueen flick I can recall seeing, and it obviously has things that the others lack.

For one thing, a lot of absolutely right decisions were made, Bibi Andersson, cast as the good doctor’s wife, works wonders with her relatively restricted material. The music is composed by the man who scored East of Eden (Leonard Rosenman); the nuanced, nicely lit cinematography is by the man who shot California Split (Paul Lohmann); best of all, the attractive, sexy sets are designed by the art director of The Rules of the Game (Eugène Lourié). The film’s opening visual effect – the gradual saturation of a sepia interior still life with a full range of colors – is one of the loveliest thing of its kind that I’ve seen since Track of the Cat.

McQueen himself does Doc Stockmann about the same way that Richard Dreyfuss plays the childlike visionary hero of Close Encounters of the Third Kind — with similar uses of benign befuddlement, but without being showy about it, And for starters, the movie is a lot less silly than Joseph Losey’s own happily forgotten 1973 stab at lbsen (with comparable proportions of lemony light, textured tablecloth, and increasing snowdrifts) and at Jane Fonda with the same pin, in A Doll’s House.

In fairness to the solemnity of the occasion, though (this takes place in a small Norwegian coastal town in the winter – no fooling around), I’m obliged to admit that director George Schaefer, a first-rate craftsman from Broadway and TV, doesn’t really follow Harold Clurman’s provocative suggestion that An Enemy of the People is a comedy — at least not for any extended stretches. Dr. Stockmann may be something of a holy fool at times, but his crusade –- to tell the people in town that the springs with which they’re beginning to attract tourists are polluted and poisoned –- remains in deadly earnest, even though there are a couple of dry references to the present. (When the doctor and his family become social outcasts and he contemplates a move to America, he also muses, “I suppose they have the moral majority, too.”)

Stockmann’s brother Peter, the town mayor — effectively if a trifle monotonously fleshed out by Charles Durning — figures as the capitalist villain who keeps his brother’s report out of the local newspaper, then effectively silences him at a town meeting. (Despite a few nuances in the part, he’s nearly as all-bad as the doctor’s loyal and courageous daughter Petra — played with real passion by Robin Pearson Rose — is all-good.) The play (which might well have influenced Jaws) is far from being major Ibsen, and an intermittent tinge of self-righteousness in the rage occasionally reminds me that this was adapted 30 years ago by Arthur Miller.

In short, this movie has all the solid virtues of a better-than-average Stanley Kramer picture in the ’50s. And it’s worth recalling that this was a time when those liberal, middlebrow virtues really counted for something. As a concluding title informs us, it’s been 98 years since this play was first performed in Oslo. But it still plays well, and I wasn’t bored for an instant.

***

Beatlemania — The Movie is a tepid bomb — grossly misconceived, lifelessly executed, randomly assembled, dutifully delivered, and frantically sold. As a multifaceted press kit, it’s something of a masterpiece. Even the awkwardly footnoted subtitle, Not the Beatles, but an incredible simulation, performs the near-miraculous task of collapsing legal protection, inauthentic existential and ontological identities, and alienated fantasy into one all-purpose selling unit.

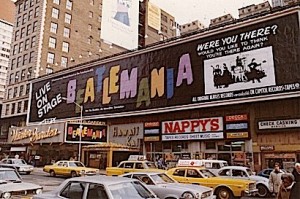

Practically speaking, Beatlemovie -– The Mania (not the Broadway hit or touring show, which juxtaposed its four Beatles impersonators singing 30 hits with slides and archive footage, and is said to have reaped $35 million) is less a product than a point of convergence, aimed at us like a speeding bullet. That it misses its crude mark is one of the few comforts it can offer. I caught it last Saturday afternoon at the Ziegfeld, the day after it opened, with fewer than 100 other lost souls and thousands of empty seats -– happy to discover that most people already knew enough to stay away. The few teenagers who were clapping along with the Muzak before the film started weren’t clapping at all long before the end.

Practically speaking, Beatlemovie -– The Mania (not the Broadway hit or touring show, which juxtaposed its four Beatles impersonators singing 30 hits with slides and archive footage, and is said to have reaped $35 million) is less a product than a point of convergence, aimed at us like a speeding bullet. That it misses its crude mark is one of the few comforts it can offer. I caught it last Saturday afternoon at the Ziegfeld, the day after it opened, with fewer than 100 other lost souls and thousands of empty seats -– happy to discover that most people already knew enough to stay away. The few teenagers who were clapping along with the Muzak before the film started weren’t clapping at all long before the end.

“How do you take a decade overloaded with revolutionary political, social, and cultural events,” begins one page in the press kit, “give it some form, and turn it into an entertaining evening?” Any movie that seeks to do this (and that regards “revolutionary political, social, and cultural events” as “overload”) is already declaring itself as an ideological machine designed precisely to sever our most meaningful links with the past, establishing artificial limbs that connect the movie to other current spinoff products in their place. I’m reminded of the General Electric pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair (“It’s a Great, Big, Beautiful Tomorrow”), which proved that, with the exercise of enough ingenuity and know-how, robots could be made to recite commercials as woodenly as most TV actors.

From a logical standpoint, any teenager who likes the Beatles and/or wants to learn something about them should go out and buy a Beatles album — not settle for any dumb “simulation” like this cheerless enema of the people. The fact that David Leon and Mitch Weissman resemble John Lennon and Paul McCartney more than either Tom Teeley or Ralph Castelli resemble George Harrison or Ringo Starr seems less vital than the fact that all four are necessarily academic, dehumanized equivalents -– and couldn’t be anything more than that for love or money.

“Visually, we tried to include those events of the decade that correlated with the underlying emotion of each song,” the director, Joe Manduke, is quoted as saying. “And through these series of events we have, hopefully, created a feeling of totality that is both exciting and entertaining. ” I can see just what he means. It’s obvious, for instance, that teletyped headlines in lights reading, “DUSTIN HOFFMAN SCORES IN THE GRADUATE,” ” ‘STAR TREK’ TOPS ON TV,” “STONES RAIDED IN LONDON,” AND “ISRAELIS AND ARABS WAGE SIX-DAY WAR,” all clearly of equal importance (like later newsreel fragments of speeches by Nixon, Wallace, and King, all similarly equated), by streaking periodically across the screen, correlate like crazy with the underlying emotion of “Can’t Buy Me Love” — obvious to someone, anyway, if not to us.

Likewise, the footage of military planes taking off with “Eleanor Rigby,” female wrestlers with “Get Back,” and car-wrecks with “The Fool on the Hill” must make some kind of sense to someone somewhere — who also probably knows in each case what the underlying emotion (and exciting and entertaining feeling of totality) is. When it comes to the use of blown-up, grainy black-and-white footage of the Selma-to-Montgomery March with “Day Tripper,” I mainly feel insulted and a little nauseated by the filmmakers’ flip cynicism about using parts of our heritage with all the delicacy of a Cuisinart — and the same disbelieving stance that I recall being expressed by racist Alabama newspapers at the time.

Beatlemania — The Movie was produced in part by Edie and Ely Landau, theatrical packagers whose ignorance about (or indifference to) film as an autonomous art or medium has been in evidence on other occasions. It seems entirely possible, therefore, that some of the crude effects and implications of the clumsy combinations of stock footage and stills with concert and other new material — like improbable Three Stooges versions of Syberberg’s Hitler, a Film from Germany — are more accidental than deliberate. For reductiveness on all levels — shrinking a lot of music, social history, and film technique to hollow and arbitrary inessentials — it probably can’t be beat, justifying a friend’s recent complaint that bad movies are worse now than they’ve ever been. But judging from An Enemy of the People, maybe mediocre films are getting better.