My column for the Summer 2016 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

J.P. Sniadecki’s feature-length The Iron Ministry (2014), available on DVD from Icarus Films, is by far the best non-Chinese documentary I’ve seen about contemporary mainland China. (Just for the record, the best Chinese documentary on the same general subject that I’ve seen is Yu-Shen Su’s far more unorthodox—and woefully still unavailable — 2012 Man Made Place; a couple of snippets are available on YouTube and Vimeo.) Filmed over three years on Chinese trains, it’s full of revelatory moments, and not only in its surprisingly outspoken interviews: the non-narrative stretches, which compare quite favourably with the more abstract portions of Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s Leviathan (2012), are pretty stunning as well. Skip this one at your peril.

Second Run’s very first Blu-ray — Pedro Costa’s Horse Money (2015) — is gorgeously transferred, and has splendid extras: Costa’s 2010 short film O nosso homem, essays by Jonathan Romney and Chris Fujiwara, an introduction to Horse Money’s introduction by Thom Andersen, and Laura Mulvey’s conversation with Costa at London’s ICA. The extras on Criterion’s Blu-ray of Jean-Luc Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964) are too numerous to mention here, but suffice it to say that just about every intertextual reference in this cherished object are teased out in one way or another.

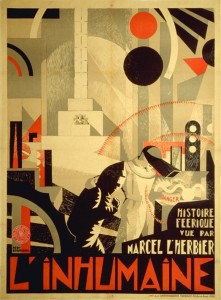

Three separate three-disc Blu-ray sets from the BFI also deserve special mention: Emir Kusturica’s 1995 Underground (including the six-part, 310-minute TV version) and two packages of Ken Russell’s best 1960s TV work, The Great Composers (including Elgar, The Debussy Film, and Song of Summer, the latter about Delius) and The Great Passions (Always on Sunday, about Henri Rousseau; Isadora, about Isadora Duncan; and Dante’s Inferno, about Dante Gabriel Rossetti). And as long as we’re on the subject of delirious mannerism, Lobster Films and Flicker Alley’s fine single-disc Blu-ray edition of Marcel L’Herbier’s 1924 L’inhumaine is almost perfect. (My only lingering complaint is that not enough clarity is offered about how much and in what way Aidje Tafial’s score — which gets a separate documentary of its own — is or isn’t related to the original Darius Milhaud score.)

It’s a lucky coincidence that Věra Chytilová’s contrapuntal 1963 feature Something Different, which came just before her celebrated Daisies (1966) — Chytilová’s own version of William Faulkner’s The Wild Palms that intercuts between a documentary about a female gymnast in training and a fictional story about a discontented housewife — should become available from Second Run on DVD around the same time that both versions of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 (1971) finally hit the Anglo-American market in separate editions, from Carlotta (US) and Arrow (UK). (I contributed to both of the latter editions, which is why I’m not saying more about them here.) The relevance of this coincidence is that Chytilová’s editing scheme, based on different kinds of formal rhymes, had as much of a visible influence on Out 1: Spectre as the colorful and crazy antics of Daisies had on Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974).

Either by coincidence or by design, the films that I regard as the two greatest paranoid fantasies of the 1960s arrived in a single package from Criterion: Blu-ray editions of Rivette’s Paris nous appartient (1961) and John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962). As different as these two features are — rambling and amateurish (albeit in the very best sense of both terms) in the case of Rivette’s debut feature, tight and streamlined in the case of Frankenheimer’s best work — I saw them both, in that order, as a freshman and sophomore at Washington Square College (the former at Cinema 16 and the latter at a commercial theatre), and I think it’s fair to describe both of them as essential New Wave productions, though for quite disparate reasons: the Rivette for its ragtag origins and its cinephilic underpinnings, the Frankenheimer for its unsettling mix of genres, oscillating between comedy and horrific tragedy as ruthlessly as Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianiste (1960). Both movies are milestones in their distillations of apocalyptic late ’50s zeitgeist, though this aspect of their importance, which is beautifully and cogently discussed in the Manchurian extras — above all, in discussions by historian Susan Carruthers (brilliantly illustrated) and, to a lesser extent, by filmmaker Errol Morris—is all but ignored on the Paris Blu-ray, whose extras are skimpy. An interview about Paris with film historian Richard Neupert (which is a bit academic for my taste) shows virtually no interest at all in the film’s meaning, and Luc Sante’s essay, adequate enough in its treatments of Rivette and the film’s production (as is Neupert), is only slightly better in grappling with the film’s metaphysics, or even acknowledging that it has a metaphysics. Both commentaries seem almost apologetic about the film, as if its haunting ambiguities and uncertainties were somehow tied only to the difficult production circumstances, and their joint implication that the film was ignored when it first appeared overlooks the rich and sensitive appreciations it received at the time in Sight and Sound and Moviegoer (to cite only two of the reviews that I still recall vividly).

Either by coincidence or by design, the films that I regard as the two greatest paranoid fantasies of the 1960s arrived in a single package from Criterion: Blu-ray editions of Rivette’s Paris nous appartient (1961) and John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962). As different as these two features are — rambling and amateurish (albeit in the very best sense of both terms) in the case of Rivette’s debut feature, tight and streamlined in the case of Frankenheimer’s best work — I saw them both, in that order, as a freshman and sophomore at Washington Square College (the former at Cinema 16 and the latter at a commercial theatre), and I think it’s fair to describe both of them as essential New Wave productions, though for quite disparate reasons: the Rivette for its ragtag origins and its cinephilic underpinnings, the Frankenheimer for its unsettling mix of genres, oscillating between comedy and horrific tragedy as ruthlessly as Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianiste (1960). Both movies are milestones in their distillations of apocalyptic late ’50s zeitgeist, though this aspect of their importance, which is beautifully and cogently discussed in the Manchurian extras — above all, in discussions by historian Susan Carruthers (brilliantly illustrated) and, to a lesser extent, by filmmaker Errol Morris—is all but ignored on the Paris Blu-ray, whose extras are skimpy. An interview about Paris with film historian Richard Neupert (which is a bit academic for my taste) shows virtually no interest at all in the film’s meaning, and Luc Sante’s essay, adequate enough in its treatments of Rivette and the film’s production (as is Neupert), is only slightly better in grappling with the film’s metaphysics, or even acknowledging that it has a metaphysics. Both commentaries seem almost apologetic about the film, as if its haunting ambiguities and uncertainties were somehow tied only to the difficult production circumstances, and their joint implication that the film was ignored when it first appeared overlooks the rich and sensitive appreciations it received at the time in Sight and Sound and Moviegoer (to cite only two of the reviews that I still recall vividly).

Watching Elaine May’s excellent American Masters profile of her former improv partner Mike Nichols in late January — a canny and subtle mixture of affectionate tribute and sly sibling-rivalry putdowns — I realized that, even though I’d long ago given up on Nichols as an interesting filmmaker (despite all his mainstream smarts), his six-hour Angels in America (2004) was obviously something I needed to see, so I ordered the two-DVD set from HBO Video and was more than amply rewarded. Thanks to the material he had to work with — Tony Kushner’s polyphonic script and many virtuoso actors, especially Al Pacino, Meryl Streep, and Jeffrey Wright — this is far and away his best film. When it comes to orchestrating special effects to attach expressive directorial arias to the performances, it even accomplishes the impossible task of synthesizing Ken Russell and Andrei Tarkovsky in order to illustrate spiritual issues involved in brassy showbiz terms that never cheat on the metaphysical stakes involved. (Mutatis mutandis, Justin Kirk’s journey back across a pond in Heaven to return to his hospital sickbed inevitably recalls the spiritual climax of Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia.)

P.S.: If, like me, you missed the hour-long Nichols and May: Take Two when it was shown long ago on American Masters, you can order a copy for only $2.99 (plus shipping and handling, which for me was $5.25) from Premiere Opera at premopera@gmail.com; while I found it a bit too sound-bitey, it’s clearly a lot better than nothing.

The following is taken from my “Cannes Journal” in the September-October 1973 issue of Film Comment and corrected in a few particulars in April 2016, after seeing the restored 128-minute director’s cut of Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street on a Blu-ray from Olive Films: “In theory, the Marché du Film is merely one division of the festival out of many (official selections, Directors’ Fortnight, Critics’ Week, etc.); in practice, every film and every person attending is on the marketplace, to purchase or to be purchased, and all the rest is journalistic euphemism. It was there, at any rate, that I came across Samuel Fuller’s latest film.

“Not all of Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street is peaches and cream, but the beginning is extraordinary — a brilliant burst of action that illustrates the title in lightning flashes — and the mad finale in a weapons room is not far behind. Fuller’s habitual obeisance to the title composer reaches an apogee of sorts in a scene set in the Beethoven Museum, where the head of one of the leads (Glenn Corbett) is cut off by the top of the frame in order to give one of the Master’s pianos a privileged place in the composition. Some of the personal/filmic references get pretty Baroque, too: a clip of Rio Bravo dubbed into German; a snippet from Alphaville to reveal an earlier acting part of Christa Lang, Fuller’s wife (seen as a prostitute servicing Akim Tamiroff); Stéphane Audran doing a guest bit as a lesbian named Dr. Bogdanovich. If this all sounds like a movie freak’s nightmare, I can only confess that Sam seemed to have a whale of a time making this two-bit classic, and I for one had a whale of a time watching it. It may not have production values like Electra Glide in Blue, a conformist crowd pleaser shown in the Grande Salle — a film that aims to out-gross the highest grossers by synthesizing at least six other ‘hits,’ heartily recommended to all viewers with like temperaments — but by God, it has style. As is customary with Fuller, the acting veers from woodblock-hard to awful-ugly (automatically turning every face into a mug shot), the violence is corrosive, the double crosses mutual, the implications perfectly bananas, the imagination fertile. As a modest entry in the Louis Feuillade tradition, this is a minor joy.”

Now that we can see it in its full-length version (24 minutes longer than its original release), Pigeon is all the more fascinating and flavoursome in terms of its sheer weirdness, and (as Christa Fuller points out) its conscious kinship with the French New Wave becomes much clearer. Another reason for getting this wonderful release is Robert Fischer’s superlative, eye-opening, 110-minute Return to Beethoven Street: Sam Fuller in Germany, which does a fine job of unpacking Fuller’s best and in some ways most neglected European film. (A minor caveat: while I agree with almost everything Bill Krohn says about the film in Fischer’s documentary, including the fact that it belongs with Fuller’s “late” period, it’s worth adding that the touristic treatment of Bonn, Cologne, and Essen still calls to mind many sequences in Fuller’s 1955 House of Bamboo, as does the ever-present Fulleresque double-agent theme, even if the narrative style is radically different.)

Long before a marketing term like “noir” came along to aestheticize such an experience, the sheer negativity of Cyril Endfield’s The Sound of Fury (another Blu-ray from Olive Films) was so shocking and disturbing in 1950 that audiences stayed away, which led the desperate distributor to retitle it Try and Get Me! — a less elegant, appropriate, or meaningful moniker, which this powerful feature has been stuck with ever since. One of the lamentable offshoots of this mislabelling is that the film’s daring opening sequence — which is connected to the remainder of the film only thematically, but not in relation to the narrative — no longer makes as much sense without the original title as a guide. But no matter: the transfer is great, and, thanks to the optional English subtitles that Olive has thoughtfully provided, I was able to notice for the first time that a neighbor and creditor of the film’s protagonist (played by Frank Lovejoy, in his greatest performance) who appears in an early sequence is named Mr. Lenin. It might be stretching things a bit to see the soon-to-be blacklisted Endfield alluding here to his communist past, but it’s still tempting to entertain such a fantasy — and even if one doesn’t, it’s hard to think of a more scorching critique of American society that emerged from early ’50s Hollywood. (Check out Brian Neve’s recent and excellent biography of Endfield for many more details.)

Mike Hodges’ A Prayer for Dying (1987) was one of the first films I reviewed for the Chicago Reader after I moved to Chicago, and, as I discovered from the Twilight Time Blu-ray (which includes an informative and level-headed recent interview with Hodges, as well as an interview with cinematographer Mike Garfath), I was flummoxed at the time by a press release about the distributor’s rejection of Hodges’ cut and the release of a re-edited and remixed cut, which led me to call the released version of Hodges’ IRA/gangster thriller “disjointed.” But as Hodges reasonably points out, reviewers such as myself who made judgment calls about this matter without having seen his own version were taking too much for granted. In fact, whatever one thinks of the film as it now stands (which flopped commercially in the US), it’s beautifully acted, expertly paced, and not at all disjointed. Hodges had the superb and unorthodox idea of switching the roles of Alan Bates and Bob Hoskins so that the former plays the gangster villain and the latter plays the sympathetic priest, and Mickey Rourke in the lead role as a guilt-stricken and angelic IRA terrorist does a remarkable job of making such an improbable character compelling. This is well worth a look.

The same goes for two other Twilight Time Blu-ray releases, Robert Parrish and Irwin Shaw’s In the French Style (1963) and Fred Zinnemann’s Julia (1977), albeit with heavy caveats in both cases: the former is a failed independent effort starring Jean Seberg (at her most luminous), while the latter is slickly engineered Oscar bait with Jane Fonda at her near-best. An important part of what made these watchable for me are the extras: Julie Kirgo’s essay about In the French Style, which gives a convincing account of how and why the film fails, and Nick Redman and Jane Fonda’s audio commentary for Julia (with Redman remembering the film much better than Fonda does, but both having much of interest to say). My demurrals mainly have to do with (a) what I take to be some of the pro-Hollywood and anti-independent biases of Kirgo, Redman, and Lem Dobbs on their audio commentary for In the French Style (all of whom seem reluctant to grant any ambiguity to Shaw’s conflicted portrait of Seberg’s character and the casting of Stanley Baker as one of her lovers), which seem to demand Hollywood simplicity from a project conceived to elude such satisfactions; and (b) the intermittent glibness and phoniness of Julia itself — especially its first half, which mainly serves as preparation for its far more purposeful and compelling second half as a resistance thriller. (Furthermore, the supposed “true-life” aspects of the plot have by now been definitively disproven, and Kirgo in her essay on this release helpfully guided me towards an online essay spelling out all the evidence.)

The Mark (available on DVD for nine quid at moviemail.com the last time I looked, but costing $125 on Amazon) moved me quite a lot for its compassion and sensitivity when I was in my late teens, and it holds up remarkably well 55 years later. In her mixed review (included in I Lost it at the Movies, but not in For Keeps), Pauline Kael did a pretty good job of discussing its thematic limitations in handling a convict on parole (Stuart Whitman) in provincial England trying to start a new life after having turned himself in for almost raping a ten-year-old girl. But she didn’t give nearly enough credit to the performances (especially by Whitman, Maria Schell, and an unusually restrained Rod Steiger) or the script (largely by Sidney Buchman, who also produced), and at least one of her other complaints struck me then—and strikes me now—as boorish philistinism: “I wish Stuart Whitman’s head, particularly from the side and back, weren’t so remarkably thick and ugly.” I wouldn’t describe Guy Green, the director, as any sort of unsung auteur, and he does a very clumsy job in handling dream sequences, but otherwise he excels in allowing the characters and story to carry the movie without getting in their way. It isn’t M, as Kael points out, but it’s a fine movie just the same.

Mervyn LeRoy was one of Sam Fuller’s favourite directors, and the non-stop (if semi-brainless) gusto of Big City Blues (1932) — the first of five features in Volume 9 of Forbidden Hollywood in the Warners Archive Collection — helps to explain why. In a mere 63 minutes, a routine low-budget time-filler breezes past with the manic urgency of a fever dream, complete with speedy, mechanically-delivered line readings, clunky but hallucinatory collage and montage stretches, and an uncredited early appearance by Humphrey Bogart halfway through in which he almost single-handedly turns a hick comedy about New York parties and hucksters into a sinister crime story where big-city brutality and indifference seem no less operative.

I still haven’t read Joseph Conrad’s first novel, but Chantal Akerman’s nervy and passionate free adaptation La Folie Almayer (2011), which I acquired on French Amazon for 19,99 Euros (a Shellac Sud DVD with optional English and Dutch subtitles), turned out to be far more substantial and absorbing than its largely negative reviews led me to expect. Even if the film finally becomes unhinged by what appears to be a disproportionate interest in its white colonialist father figure (Stanislaus Merhar), it is still a rather exciting attempt by Akerman to stretch the boundaries of her art—most notably in the film’s opening and closing sequences, but also in the beautiful handling of landscapes.

Despite Orson Welles’ effective turn as Clarence Darrow (under a fictional disguise), Compulsion (1959) is far from the best of Richard Fleischer’s crime pictures; just for starters, I much prefer The Narrow Margin (1952), which I have under the title L’Enigme de Chicago Express from an Editions Montparnasse DVD, The Boston Strangler (1968), and 10 Rillington Place (1971), and others might wish to add The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing and Violent Saturday (both 1955). But if you plunk down thirteen quid and order the Compulsion Blu-ray from English Amazon, you’ll get a wealth of material about Fleischer’s career in two extended interviews given at the National Film Theatre (from 1981, in audio only, and from 1994, with sound and image), which helps to compensate for Compulsion’s awkward sidestepping of the gay context of the Leopold and Loeb murder case, which Hitchcock had dealt with far more forthrightly over a decade earlier in Rope (1948). And without quite claiming that Fleischer necessarily deserves to be celebrated as an auteur, it’s still worth noting how masterfully he deals with confined spaces in The Narrow Margin, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1952), and 10 Rillington Place. My other favourite Fleischers — 20,000 Leagues, The Vikings (1958), and Mandingo (1975) — are also available on Blu-rays, but neither of the two editions of Mandingo available from Legend and Olive includes any extras; to supplement this shocking (and shockingly underrated and misread) Gothic masterpiece, inexcusably ground underfoot by the much sillier Django Unchained, you should hunt down the interview with Fleischer in Movie no. 22 (Spring 1976) as well as the detailed defenses of the film by Robin Wood and Andrew Britton. It’s worth adding that (a) the new Kino Lorber Blu-ray of The Vikings includes Fleischer’s promotional “featurette” A Tale of Norway, which understandably omits the director’s lingering irritation with the prima donna attitude of the film’s producer and star Kirk Douglas (which Fleischer freely aired at the NFT); and (b) the two-disc “special edition” Blu-ray edition of 20,000 Leagues from Disney, with a shitload of extras, can be purchased on Amazon for only $9.99.

On the Criterion Blu-ray of Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Michael Sragow should be applauded for demonstrating that James Agee identified Howard Hawks as an important personal filmmaker before either Jacques Rivette or Manny Farber (in his 1948 Time review of Red River that was excluded from Agee on Film, but included in Sragow’s own Agee collection for the Library of America). And on the same release, I’m grateful to Craig Barron and Ben Burtt for their scholarly extra Howard Hawks and His Aviation Movies, even if I remain uneasy about the title: we get detailed comments from them about The Dawn Patrol (1930) and Only Angels Have Wings and passing remarks about a few others, such as Ceiling Zero (1936), but not even the barest mention of Air Force (1943). Both the latter film and The Dawn Patrol, incidentally, are now available on Warner Archive DVDs.

Thanks to the Kino Lorber Blu-ray, I’ve now seen the UCLA restoration of Arthur Ripley’s 1946 cult noir item The Chase twice, having missed it in all its speckled and dupey public-domain versions. To be perfectly honest, I can’t say I was won over by it, although its status as a murky, quasi-camp curiosity encouraged me to watch it a second time with Guy Maddin’s charming if somewhat discombobulated audio-commentary—truthfully, the major reason why I requested a review copy of this release—which enhanced my appreciation of it without quite turning me into an acolyte. Two radio adaptations of the movie’s source novel, Cornell Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear, starring Brian Donlevy and Cary Grant, are also included. Without being a fraction as good as either The Window (1949) or Rear Window (1954), Roy Rowland’s 1954 Witness to Murder (included in Kino Lorber’s five-disc Blu-ray collection Film Noir: The Dark Side of Cinema) is, as its title suggests, a thriller with a similar premise, although in this case the murderer (George Sanders) is followed from the beginning as well as the witness/neighbour (Barbara Stanwyck). Before the movie slides into formulaic and predictable drivel (which starts around the time that Sanders’ character, an ex-Nazi, starts spouting German), it’s pretty edgy and scary stuff, helped along by superb cinematography from John Alton and a capacity for telling most of the story in terms of details, observations, and deductions without any dialogue. I suspect the principal auteur here is producer-writer Chester Erskine, though it’s worth adding that both Ted Geisel (i.e., Dr. Seuss) and Janet Leigh expressed some affection and admiration for Rowland, a mainly unsung director, in separate conversations with me.

I’ve been slow to catch up with such warhorses as Jezebel (1938), Dark Victory (1939), Now, Voyager (1942), and Old Acquaintance (1943) because I’ve never quite understood the logic of Bette Davis. But now that a brilliant essay about her by Murielle Joudet in the online journal Lola has explained it all to me in fulsome detail, the Turner Classic Movies two-disc Greatest Classic Legends set containing these features and many extras has come in very handy.