From Cinema Scope issue 39, Summer 2014. — J.R.

I shelled out $56.19 in US dollars (including postage) to acquire the definitive and restored, director-approved DVD of Providence (1977) from French Amazon, and I hasten to add that this was money well spent. Notwithstanding the passion and brilliance of Alain Resnais’ first two features, Providence is in many ways my favourite of his longer works, quite apart from the fact that it’s the only one in English. And I can’t ascribe this preference simply to the contribution of David Mercer (1928-1980). I recently resaw the only other Mercer-scripted film I’m familiar with, Karel Reisz’s Morgan!, and aside from the wit of its own sarcastic dialogue I mainly found it just as flat and tiresome as I did in 1966, for reasons that are well expounded in Dwight Macdonald’s contemporary review (reprinted in his collection On Movies).

I haven’t yet been able to see The Life of Riley (Aimer, boire et chanter), Resnais’ swan song, but clearly part of what gives Providence even more resonance now, writing less than a month after Resnais’ death, is the theme it shares with his penultimate feature, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet (2013): an old writer facing his own death, and trying to create some form of art in relation to it. (John Gielgud’s performance as the old writer is for me one of the greatest bits of film acting that we have, and Dirk Bogarde’s superb rendition of the writer’s emotionally repressed older son may be as much of a self-portrait on Resnais’ part.)

The DVD has some fascinating extras: François Thomas’ very informative 29-minute audio interview with Resnais about the film (which Resnais conceived from the outset as a “documentary about imagination”) and a 51-minute documentary including detailed interviews with art director Jacques Saulnier, cinematographer Ricardo Aronovich, and actor Pierre Arditi (who doesn’t appear in Providence, but whose work with Resnais in countless other films still gives him plenty to talk about), both thoughtfully provided with optional English subtitles. The single-disc set also includes both the original English and the French post-dubbed versions of the film (the latter of which Resnais supervised, and which includes many of the most famous actors in French cinema, even though the lip-sync isn’t always up to the line readings).

On the box is a quote from Norman Mailer, of all people: “Le meilleur film jamais réalisé sur le processus de création,” which translates as “The greatest film ever made on the creative process,” and it’s surely telling that I had to go to a French source to come upon such an apt and just description of this vibrant masterpiece. On the other hand, go to James Wolcott, one of Mailer’s protégés, and you’ll find him actually bragging about helping to create a ruckus with another of his mentors, Pauline Kael, at a New York press screening for having “dared take Alain Resnais’ Providence (a meditation on death and creativity endorsed by Susan Sontag, swinging her incense ball) less than solemnly.” I guess those courageous pranksters and truth-tellers just didn’t dig how much of Providence is a comedy. Too bad I was off in Europe during most of the mid-’70s; otherwise I might have been around to hoot and jeer at Kael and Wolcott swinging their own solemn incense balls to greet the far less witty pomposity of The Godfather Part II (1974).

***

One shouldn’t be put off by the fact that Martina Kudláček’s astonishing Fragments of Kubelka (2012), released on an impeccable two-disc set from the Austrian Filmmuseum (and available from German Amazon for 22,99 Euros), is almost four hours long, for it’s hard to think of a better way to spend those 232 minutes. Jonas Mekas has called it “the best film on any artist that I‘ve ever seen,” and I’d certainly hesitate before calling his assertion hyperbolic. At the very least, Kubelka’s climactic cooking and eating of wiener schnitzel at the end of the film functions as a definitive expression of his vision, which encompasses his own variants of Borges’ “New Refutation of Time” and Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” along with a lot more.

To the same degree that Providence remains a profound meditation on death, Kubelka’s presentation of what he thinks and does about film, art, music, artifacts, language, time, space, food, and cooking is a bracing celebration of life, and Kudláček—who already showed her smarts and sensitivity in coping with the works and lives of Alexander Hammid, Maya Deren, and Marie Menken—surpasses herself here while sticking rigourously to Kubelka’s own baselines by refusing subtitles (the film is almost entirely in English, and very easy to follow) and showing none of Kubelka’s analog films in her digital format while allowing Kubelka to teach us a great deal about most of them. Following the same principle of non-translation, the 16-page booklet includes essays by Tom Gunning (in English), Christian Höller (in German), and Nicole Brenez (in French), and I can vouch for the fact that the first and third of these are very beautiful appreciations of both Kubelka and this film.

***

A film about Chris Marker is always welcome, so I was happy to see To Chris Marker: An Unsent Letter—completed shortly after Marker’s death by Emiko Omori, one of the cinematographers on his French TV series The Owl’s Legacy (1989)—on a DVD from Icarus Home Video, even if it offers something less than a proper survey of his life and career. (I suspect that Marker’s own reticence about himself and his reluctance to show many of his early films curtailed many of Omori’s choices.) But I was happier to receive, from the same label, the long-unavailable Far from Vietnam (1967), which Marker organized and edited, with his 26-minute The Sixth Side of the Pentagon, made the same year, included as an extra.

Part of what keeps many portions of Marker’s life and work beyond our reach are his special gifts as a collaborator, and Far from Vietnam remains one of the most precious examples of that talent. Made and received as a work of unabashed agitprop — I can still recall some of the booing it elicited when it received its premiere showing at the New York Film Festival — it is also a precious historical document (let’s even say a marker) of the triangulated relationships between France, the US, and Vietnam during the mid-’60s, expressed through the combined efforts of Marker, Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda.

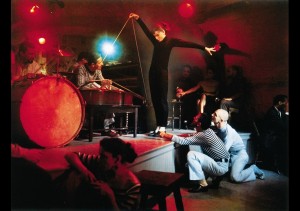

The most frustrating example of this triangulation is Chapter 5 on the DVD, the episode made by Resnais, Jacques Sternberg (who was scripting Resnais’ Je t’aime, je t’aime around the same time), and Bernard Fresson (the actor who played the German soldier in Hiroshima, mon amour, here playing the fictional character Claude Ridder, named after the hero of Je t’aime, je t’aime). It seems to express inadvertently the unbreachable distance between French and American styles of self-scrutiny — an anguished monologue delivered by Fresson’s character in his flat that remains unpalatable to American tastes, especially due to the repeated reaction shots of Ridder’s morose-looking wife or girlfriend listening sympathetically to his rant without uttering a peep. The precise opposite to this, and for me the most powerful of all the sequences, is Chapter 11, entitled “Ann Uyen” and shot by Klein, which intercuts between Ann, the widow of Norman Morrison (the Quaker who burned himself in front of the Pentagon), with her children in Baltimore [see above photo], and a Vietnamese woman named Uyen with her own children in Paris explaining how much this gesture by Morrison and the acceptance of this gesture by his widow means to her and other Vietnamese people. The other two sequences that stay with me the most are Chapter 3, “A Parade is a Parade,” also shot mostly or entirely by Klein, featuring an anti-war demonstration in Paris and both pro-war and anti-war demonstrations in Manhattan, and Chapter 7, “Camera Eye,” with and by Godard. But these are only the most notable parts of a two-hour film that continues to resonate—and even served as the model for Far from Afghanistan, by John Gianvito, Jon Jost and others a couple of years ago.

***

A punishing illustration of the maxim that history is written by its victors rather than its victims, the TCM Vault Collection’s typically scattershot and somewhat absent-minded dual-format edition of The Lady from Shanghai (1947) focuses mainly on kitschy publicity materials from Columbia, a poorly researched podcast, and a previously used audio commentary by Peter Bogdanovich (not one of his best) that chiefly relies on reading aloud portions of This is Orson Welles before belatedly and incompletely (albeit tactfully) correcting some of Welles’ misstatements in it. Furthermore, and typically for TCM Vault releases, no subtitles of any kind are included. The most factually reliable material comes in an onscreen essay that the lazier film buffs probably won’t bother with, but to get an inkling of what the 155-minute rough cut consisted of, you’ll have to turn to the final chapter of the second edition of James Naremore’s irreplaceable The Magic World of Orson Welles.

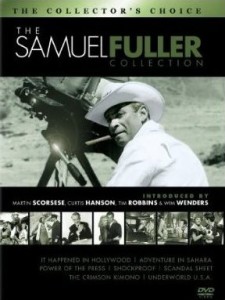

A much more creditable offering from TCM is their seven-disc Samuel Fuller Collection — the only catch being that five of the seven features included are written but not directed by Fuller. This doesn’t contradict the way that Fuller saw himself, which was basically as a writer who became a director to protect and serve his own scripts, like the otherwise very different Billy Wilder. But grateful as I am to have finally caught up with the Fuller-scripted It Happened in Hollywood (1937), Adventure in Sahara (1938), and Power of the Press (1943)—and to have the opportunity to re-see Douglas Sirk’s Shockproof (1949) and Phil Karlson’s Scandal Sheet (1952)—I’m not sure that I need to see these first three titles more than once, unlike the Fuller-directed The Crimson Kimono (1959)—which remains, along with White Dog (1982), the most remarkable of all Fuller’s films about racism—and Underworld U.S.A. (1961). The four extras in this package, featuring commentaries by Christa and Samantha Fuller, Curtis Hanson, Tim Robbins, Martin Scorsese, and Wim Wenders, are also quite welcome.

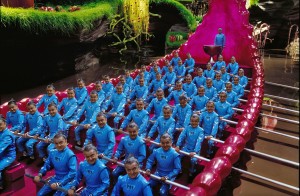

An even finer and genuinely thoughtful production is the Warners Blu-ray of Tim Burton’s sublime Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005)—released well over two years ago, although I’ve only just caught up with it. What now appears to be Burton’s masterpiece to date, both for its wealth of free-flowing invention and its superb architecture (both as a film and as a triumph of set design), is enhanced by extras that are tricky to track and navigate (much like the film’s title factory) but well worth the trouble of discovering. Alas, I can’t say the same for the Blu-ray of Burton’s Mars Attacks! (1996), which includes no extras of any kind.

***

Arrow Academy in the UK, whose superb edition of The Long Goodbye (1973) I heralded in my last column, has sent me a package of their more recent releases, including Don Siegel’s The Killers (1964), Donald Cammell’s White of the Eye (1987), and Brian De Palma’s Sisters (1973) and Phantom of the Paradise (1974). The extras here are comparably noteworthy. The first has an excellent archival interview with Siegel from French television as well as informative new features about both Lee Marvin and Ronald Reagan, while the second includes (along with much else) a feature-length documentary about Cammell from British television and an interesting essay by Brad Stevens. Phantom of the Paradise really isn’t my cup of tea, so I couldn’t do much with either the film or its reverential extras, but Sisters offers (also along with much else) an impressive critical “De Palma Digest” by Mike Sutton taking us through the director’s entire filmography — although for my money the best possible extra for this particular film has to be found elsewhere, in the De Palma chapter of Robin Wood’s Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond.

One nagging question that I have about The Killers — an unusually nasty hit-man movie with one of Marvin’s better performances — goes unanswered. The music over the opening credits is a direct steal from Henry Mancini’s score for Touch of Evil (1958), but those same credits assign the score of this film solely to John Williams, crediting Mancini only for a song that Nancy Wilson sings in a nightclub sequence. Is this the same score that was used in the film when it was first released, or has some skullduggery on the part of Universal due to rights issues intervened (the same sort of skullduggery performed by other studios on the DVDs of A New Leaf [1971] and California Split [1974])? Although I saw The Killers (or Ernest Hemingway’s The Killers, as Universal capriciously and inaccurately insisted on calling it, over Siegel’s understandable protests) back in 1964, I no longer remember.

***

Largely, I suspect, for temperamental reasons, I’ve never been much of a fan of William Friedkin. But the DVD release of a restored version of his first feature The People vs. Paul Crump (1962) on Facets Video — with superb documentation by Susan Doll and whoever else wrote the unsigned second essay in the 14-page booklet — clarifies that the undeserved obscurity today of this striking and provocative docudrama (or documentary with restaged fictional segments) is chiefly due to the unruliness of history, especially when it conflicts with an easily digestible narrative and moral thrust. (I suppose the same argument could be made now for Friedkin’s Sorcerer (1977), also just out on DVD and getting far more attention than The People vs. Paul Crump, but I must confess that I have far less interest in returning to that piece of macho-bluff.) Friedkin made this film almost a decade after Paul Crump was sentenced to the electric chair for killing a security guard during a 1953 payroll robbery at a Chicago meat-packing plant, yet by the time Crump died almost half a century later, after 39 years in prison, so much had happened to complicate his case and his life that Friedkin’s made-for-TV film can only seem out of date in any activist context. But the editing alone, along with much else, makes it a fascinating and notable experiment, well worth a look.

***

Full disclosure: the press release for a lovely new Blu-ray from Twilight Time quotes a phrase from my Chicago Reader capsule: “One of the best Hollywood weepies of the ’50s, comparable to the best of Douglas Sirk in both its imaginative mise en scène and its strong feeling.” Fuller disclosure — here is the final sentence of the first paragraph of Julie Kirgo’s essay accompanying this release: “So go ahead, cynics, call The Eddy Duchin Story (1956) a weepie; the rest of us will sit back, smile, and call it for what it is: a classic.”

Since I also like to sit back and smile, and don’t regard myself as any sort of cynic, might I propose an armistice — that we all agree to call The Eddy Duchin Story a classic weepie? I certainly don’t equate “weepie” with “women’s picture,” fully subscribing to the late Raymond Durgnat’s postulation of a category known as the “male weepie” (which includes, among many other noble contenders, Bicycle Thieves [1948]). In other words, I’m one of those who was (at age 13) and still am (at age 71) one of the unapologetic and non-cynical weepers this classic weepie was made for, and I further happen to be the proud owner of a poster for The Eddy Duchin Story signed by Kim Novak that I can see from my breakfast table. While I can’t vouch for Kirgo’s claim that the film substitutes Tavern on the Green for the long-gone Central Park Casino where pianist Duchin made his glitzy Manhattan debut — according to my father, who programmed the movie in Alabama when it came out, wrote a Sunday newspaper column about it, and recalled Duchin playing at the Casino during his college days, it was “rebuilt” as a “temporary structure,” presumably as a set, for the movie; see page 126 of my memoir Moving Places — and whatever the likely biographical distortions and hokey melodramatic upheavals in the plot, I still consider the movie an authentic work of art, epitomized in a lovely line uttered by Tyrone Power’s Duchin (and written by Samuel Taylor): “Look at the speed of the river. It’s strange how unreal the real can be.” Power himself has never been one of my favourite actors, but he surpasses himself here not only in his tragic performance but also in his uncanny mimes of Duchin’s piano runs, even when he occasionally slides down the keyboard while the music is cascading into the upper octaves. And the film’s final camera movement, the apotheosis of George Sidney’s powerful mise en scène, has got to be one of the most exquisite in the history of Hollywood.

A day later, I watch an even greater weepie from a decade earlier, Brief Encounter (in Criterion’s four-DVD box set David Lean Directs Noel Coward), and it immediately becomes apparent to me why Robert Bresson once cited this 1945 heartbreaker as one of his ten favourite films. I’m thinking not only of what might be described as the brute delicacy of its emotional thrust (with roaring trains and Rachmaninoff vying with the repressed and unfulfilled longings of souls in hiding), but also for the contrapuntal boldness of Celia Johnson’s off-screen narration, addressed to herself yet couched in the form of a confession to her husband. The film is quite radical in other respects as well, employing expressionistic lighting changes and tilted angles at key moments, and even takes the risk of departing from its own point-of-view narration to include an edgy conversation between Trevor Howard and a male friend after Johnson has fled from the scene.

A bit sheepishly, I’m forced to confront the possibility that it may have been the huge popularity of this film when it came out that has kept me from revisiting it any sooner — the suspicion that a film so universally loved and respected must have something wrong with it. But then again, I don’t feel the same way about William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), a film that for me grows in impact and stature every time I revisit it. This is clearly another case of the audience having been right—leading Billy Wilder (or George Axelrod, or some combination thereof) to appropriate the same Rachmaninoff piano concerto in The Seven Year Itch (1955) as a way of parodying both Brief Encounter and the public’s susceptibility to its power.

***

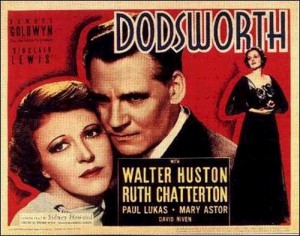

Speaking of Wyler, I only recently got around to seeing his superbly acted 1936 Dodsworth (with Walter Huston, Ruth Chatterton, Mary Astor, and Maria Ouspenskaya the principal standouts) for the first time. But in order to do so, I had to order it from abroad: the current price for the DVD on American Amazon is $89.99, but when I went to Italian Amazon, where it sells under the title Infedelta’, I could order a good copy for under ten Euros. (Still later, I discovered another edition there as well for less than five Euros, but can’t vouch for whether or not this one includes the original English language soundtrack, as the other one does.)

***

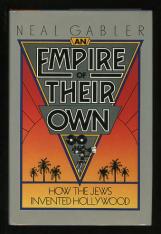

William Dieterle’s The Life of Emile Zola (1937) and Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1961): two justly despised Oscar winners, even though both have their occasional compensations (e.g., some high-flown courtroom rhetoric in the former, Maximilian Schell in the latter). Both also carry some ideological interest if one follows the juicy overall insight of Neal Gabler’s invaluable An Empire of Their Own: How The Jews Invented Hollywood — that Hollywood’s American Dream is largely founded on the rock of ethnic (specifically Jewish) self-denial. For both these movies about anti-Semitism go out of their way to force Judaism into the discreet margins of their discourse — especially the former, which dares to use the word “Jewish” only once (and in writing, glimpsed only momentarily, not in speech), but also to some degree the latter, calling on the likes of Montgomery Clift and Judy Garland to articulate the facts of Jewish suffering. If the going DVD prices are reflective of the contemporary appeal of these two didactic history-lesson talkfests, it’s worth noting that Emile Zola usually sells these days for about $5 on Amazon whereas Nuremberg’s prices, the last time I looked, ranged from $45.90 to $112.50. (I ordered my own copy of the latter from Spanish Amazon—a mere 4,95 Euros plus postage.)

Both literally and figuratively rather empty, Alain Robbe-Grillet’s first feature L’immortelle (1963), on Blu-ray from Kino Lorber, was nonetheless worth a look for at least two reasons: (1) displaying the same sort of spatial and temporal/ chronological discontinuity and disorientation (not to mention half-frozen tableaux of ritzy gatherings) found in Robbe-Grillet’s first script to be filmed, i.e., Marienbad, and (2) Robbe-Grillet’s half-hour interview about it, recounting both its tortured production history and what he subsequently came to realize were his own errors in directing it, such as turning Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, the male lead, into a block of wood.

From Olive Films, Robert Parrish’s unusually gritty and caustic crime story Cry Danger — which was deservedly awarded by Manny Farber one of his “six-inch Emmanuels” for 1951 — is notably misogynistic, yet no less misanthropic when it comes to nearly all of its male characters, with the possible exception of an ex-marine and full-time alcoholic with a wooden leg (played by Richard Erdman), who is affectionately pitied.

Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1964), also from Olive, is impressive and godawful in roughly equal measures: great new York street photography by Boris Kaufman, possibly the worst use of big-band jazz (by Quincy Jones) ever perpetrated in any feature film, a flurry of rapid montage effects that are equally square and strident, and a lead performance by Rod Steiger that runs the gamut from nuanced and thoughtful to bombastically overwrought.

***

Love Happy (1950), the Marx Brothers’ last movie, on a Blu-ray from Olive, may well have been the first of their features I ever saw. It’s certainly no Duck Soup (1933), but thanks to a story written by Harpo (who makes himself the virtual hero) and a script co-authored by Frank Tashlin, it may be their strangest outing, with lots of Tashlinesque gags involving hyperbolic dominatrices (mainly Ilona Massey, but also Vera-Ellen), huge outdoor advertising (complete with product plugs, and including some anticipations of Tashlin’s Artists and Models [1955]), and the sort of free-form, cascading delirium that we associate with animated cartoons. Groucho is basically reduced to the role of narrator and a few fleeting appearances as a detective (chasing at one point Marilyn Monroe, in an early walk-on), and I assume it must be his relative scarcity plus the low production values that has kept this rough gem undervalued.

***

In spite of its many pleasures, I’ve always had some resistance to Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (1956) because of the sheer dumbness of its story, which offends me much more than the dopiness of Love Happy because it’s supposed to be smart. I realize that musical plots are sometimes just mechanisms for carrying us from one number to the next, and I wouldn’t even mind the jeering putdown of French intellectuals and existentialism if there were any sort of wit or observation behind it instead of a lot of expedient stupidity, which spills over into the muddled conception of Audrey Hepburn’s character as well. But I’m glad I ordered the Warner Video Blu-ray just the same, and not only because of all its documentary extras, which include a pocket history of VistaVision — in which Bill Krohn offers a bit of production history about To Catch a Thief [1955] which helps to explain why it is stylistically inferior to the Hitchcock VistaVision pictures that followed it — and a feature about Kay Thompson that belatedly informed me who she was, and which includes the convincing argument that she manages to steal the show from Fred Astaire when they perform a number together for the ersatz French intelligentsia. On the other hand, I could have done without Drew Casper’s dubious assertion in another segment that Funny Face’s location shooting was an “innovation.” (What about On the Town in 1949, which Donen co-directed? And why, for that matter, do the studio-shot sequences in both movies go unmentioned?) Among the other treats in the movie proper are the opening “Think Pink” number and the Parisian photo shoot, where the sumptuous employments of colour are especially striking.

***

For $20 plus postage, via Amazon, you can order a 128-page collection catalogue produced by Philadelphia’s International House to accompany an interesting retrospective earlier this year, Free to Love: The Cinema of the Sexual Revolution, with texts by J. Hoberman, Elena Gorfinkel, Barbara Hammer, Jesse Pires, Eric Schaefer, and Herb Shellenberger, among others. As an extra, the package includes a 16-minute DVD including three shorts in the program: Lisa Crafts’ delirious and lively hardcore animated cartoon Desire Pie (1976), Dirk Kortz’s rather hackneyed slapstick farce A Quickie (1970), and John Knoop’s hardcore and experimental Norien Ten (1972).

***

Having grown up in the Muscle Shoals area in northwestern Alabama, I’m grateful for the intricate and fascinating history offered by Greg “Freddy” Camalier’s 2013 documentary about its local music-recording scene, Muscle Shoals, available on both Blu-ray and DVD from Magnolia Home Entertainment. Practically all of this history unfolded after I migrated north, but my acquaintance with a few fragments of the prehistory — including my friendship with Tom Stafford, a few informal jam sessions with Donnie Fritts, and an actual demo tape I once made with James Joiner of a sarcastic little ditty I wrote called “The A-Bomb Boogie” — made me welcome Camalier’s informative account of all that came afterwards, oriented around two recording studios. My only misgivings, relatively minor, relate to the fact that history, folk mythology, and simple promo are often difficult to distinguish in this particular world, and I wouldn’t go to Muscle Shoals in order to find out much about the larger town I grew up in, Florence (located directly across the Tennessee River from Muscle Shoals), or the other neighbouring towns of Sheffield and Tuscumbia. Even though local talents form much of the hub of what Camalier has to impart, I couldn’t help but feel that it’s the view of tourists that predominates.

***

King of the Hill (1993) and The Underneath (1995). I have to admit that I started out as mainly sympathetic to Steven Soderbergh and gradually turned against him around the same time that he and his work appeared to become more cynical (which, if I’m not mistaken, is around the same time that some of my colleagues seemed to become more invested in him, perhaps for the same reason). I don’t want to oversimplify this overall trajectory, because Soderbergh’s second feature, Kafka (1991), was already pretty dopey, and I should admit that my personal irritation with Soderbergh’s inside-the-Hollywood-bubble thinking was already set in motion when I read him complaining to Richard Lester in an interview that critics had missed the boat with Jacques Tati—which, like Michael Herr’s complaint that critics had missed the boat with Eyes Wide Shut (1999) or Robert Altman’s frequent dismissal of the entire critical community, was in effect an assertion that the only critics who mattered were high-profile, mainstream middle-of-the-roaders like David Denby and Vincent Canby, who functioned for Soderbergh, Herr, and Altman mainly as flackmeisters (and, of course, Soderbergh was wrong even there, because Canby had loved Playtime [1967]).

Nevertheless, without any longer feeling obliged to keep up with all of Soderbergh’s features (especially his many recent items built around his obsession with what it means to be a prostitute), I’ve persisted in regarding King of the Hill and The Underneath, most especially the latter, as notable exceptions to his overall decline (along with his subsequent The Limey [1999] and Bubble [2005]), so I can only welcome the re-release of these two early features by Criterion. But Soderbergh’s own dislike for The Underneath apparently had to be honoured in order for this to happen, so what we get is a dual-format release of King of the Hill in which The Underneath gets snuck in rather sheepishly as an extra, getting mentioned on the box only if you bother to read the fine print; and then it gets saddled on both the DVD and Blu-ray versions with an extended account by Soderbergh of why he doesn’t like it (apart from conceding that he does like the expressionist distortions of a hospital room, one of the film’s finer achievements). It’s understandable, of course, how Soderbergh might dislike this movie because, as he explains at one point, his marriage was breaking up at the time, but it’s inexplicable to me why I should dislike the movie for the same reason—and most of the other reasons he gives (e.g., his dissatisfactions with the filming and editing of dialogue around a dinner table) strike me as equally unpersuasive and irrelevant to my own interests. (For a far more convincing estimation of the film’s strengths and weaknesses, check out the three-page analysis in James Naremore’s More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts.)

***

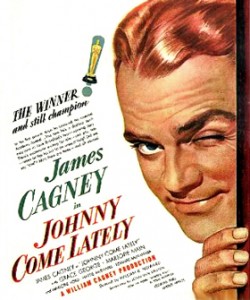

Obviously too sweet, good-natured, and anti-capitalist for its own good, because it bombed with the public and critics alike, James Cagney’s independently produced Johnny Come Lately (1943), directed by William K. Howard (another Blu-ray from Olive), moved Patrick McGilligan to call it, in his Cagney: The Actor as Auteur, “the most personal cinematic accomplishment” of his subject’s career. With almost every character in the movie a different kind of lovable eccentric, most often middle-aged (with special shared honours to Grace George, Marjorie Main, Hattie McDaniel, and Edward McNamara), planted in a hopelessly nostalgic small-town yesteryear, it’s hard to resist at least some of the film’s charm and optimism, even if it’s almost impossible to swallow all of it. As usual, no extras from Olive, but check out the McGillgan book for more information.

***

Two particular circumstances made me especially primed for Kyle Armstrong’s gorgeous 12-minute experimental short Magnetic Reconnection, available on Blu-ray with many extras (including five other Armstrong films) from HYPERLINK “http://magneticreconnection.ca” \t “_blank” http://magneticreconnection.ca

for $23 Canadian and a modest shipping cost: (1) at a boarding school in Vermont circa 1960, I was once privileged to witness the Northern Lights (aurora borealis), and I’d been wondering ever since if I would ever be able to witness such a spectacular event on film, and (2) I saw this Blu-ray, kindly sent to me its co-producer and co-cinematographer Trond Trondsen (the co-founder of the Masters of Cinema DVD and Blu-ray label), very shortly after seeing for the first time Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive (which I like somewhat more than the editor of this column, Andrew Tracy, despite some shared reservations), with its own intimations of both millennia and timelessness. Magnetic Reconnection juxtaposes the Northern Lights in all their uncanny splendour with decaying manmade debris (including an airplane and ship) in and around Churchill, Manitoba in northern Canada, which makes the relevance of the Jarmusch film even sharper, at least to me. But it may also be relevant to note that Werner Herzog is another big fan.