From Cinema Scope (Spring 2005, issue 22). The down side of reproducing my old DVD columns is that many of the links are bound to be out of date and no longer functional; the up side is that they offer some kind of history of what used to be available (or unavailable). — J.R.

With the exception of a few film buffs at some of the more discerning labels, and still fewer at the major studios, decisions about what older films to release on DVD, as well as when or why, are often capricious to the point of absurdity. So asking why some things are readily available and some things aren’t is a bit like asking an illiterate about his or her reading taste. Some time ago, I was contacted about contributing to the extras of an ambitious DVD being planned for Elaine May’s infamous and underappreciated Ishtar — a project developed with loving care by some maverick film buffs at Columbia/Tristar over many months, eventually soliciting the unprecedented cooperation and input of May herself.

It seemed like a golden opportunity for some thoughtful studio revisionism — especially in light of how much this prescient farce has to say about the dangerous blunders of American innocence and stupidity in the Middle East and how blind American reviewers were to this aspect of the movie back in 1987. Indeed, a recent spot check of the unadorned VHS version of Ishtar on Amazon revealed that 73 customer reviews were posted with an overall average rating of four and a half stars, suggesting that the audience by now is well ahead of most critics on this score. But only a few days after I enthusiastically accepted the film buffs’ invitation, a studio executive nixed the whole project without a second thought, letting perhaps a year of concerted planning go down the drain. And Ishtar, which recently came out on DVD in the U.K., remains unavailable in that format in North America. [Note in 2014: It’s available now.]

I’m also pondering the strangeness of the fact that Alain Resnais’ gorgeous 1920s-style musical Pas sur la bouche (Not on the Lips), released in France in late 2003, is still unseen and undistributed in the U.S. in any form [2014: it’s available now, albeit expensive], yet it’s recently become available with removable English, “traditional Chinese,” or “simplified Chinese” subtitles on a Hong Kong label. I just ordered it from Poker Industries, so I can’t yet vouch for either the transfer or the translation. (For a version without subtitles, the French DVD, which also includes a CD of the soundtrack score, seems letter perfect.) A world apart from Resnais’ previous musical, On connait la chanson (Same Old Song) — which seems to require a comprehensive knowledge of French pop tunes over several decades for genuine appreciation, making it probably the most “local” of Resnais’ films — Pas sur la bouche seems thoroughly steeped not only in Lubitsch (already a key Resnais cross-reference in Stavisky…) but also, more anachronistically and mysteriously, in color MGM musicals of the 40s and 50s, which Resnais appears to know like the back of his hand.

Furthermore, the central “ugly” American character played by Lambert Wilson, who sings the title tune and sports a tortured American accent, is possibly funnier to French audiences today than he might have been in the 20s, 30s, 40s or 50s–suggesting that, like Mélo, Resnais’ last major effort before this one (still available on a Region 2 PAL DVD with English subtitles from MK2 Editions), this is profoundly a film of the present. And the fact that residents of Hong Kong are more apt to appreciate this than Americans is my favorite anomaly of the quarter.

***

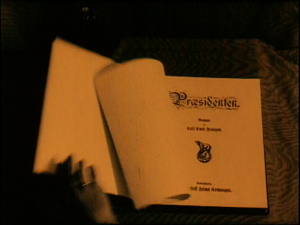

It’s also anomalous, though in a more positive way, that a great filmmaker whose works were (and are) as difficult to see as those of Carl Dreyer, especially in good prints, is fast becoming one of the best represented major foreign filmmakers on DVDs with English subtitles. Criterion has already brought us excellent restorations of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1927), Day of Wrath (1944), Ordet (1954), and Gertrud (1964), and Masters of Cinema has done the same for Michael (1924). I haven’t yet had an opportunity to check Image Entertainment’s editions of The Parson’s Widow (1920) and Vampyr (1932), and I’m still waiting with baited breath for someone to bring out his two 1925 features, Master of the House and The Bride of Glomdal. (I can exercise more patience when it comes to the 1919 Leaves from Satan’s Book and the 1944 Two People — though of course it would be good to have these as well.) And now the Danish Film Institute — whose restoration of the still-incomplete, 1922 Once Upon a Time I’ve already praised in this column — has brought out its tinted restoration of Dreyer’s first film, The President (1919),with combined Danish and English intertitles. You can order your own copy from http://eshop.dfi.dk/

***

Or consider that the beautifully letterboxed and uncut version of Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents (1960) on DVD, which I can thank Chris Fujiwara for alerting me to, is on a Spanish label, Suevia Films. It’s far more logical that the only DVD of Orson Welles’ Chimes at Midnight — recently on sale for about $15 at Xploited Cinema’s web site (where you can also purchase the Ray film) — is Spanish, because that film was shot in Spain and partly financed there. But Ray’s sublime parable about Eskimos is an Italian-British-French coproduction, shot on location in Alaska and in studios in London and Rome, and distributed in the U.S. by Paramount…so why Spain? It must be because of Spanish cinephiles.

I hadn’t seen the film in ages (which isn’t surprising given how scarce it is, especially in Panavision), so it was interesting to discover some of the ways I’d misremembered it, mainly to its disadvantage. Thanks to the film’s own anomalies –a beautifully crafted script that Ray apparently wrote single-handedly and which depends on oddly stylized and coded English dialogue; a wholly functional narration that periodically sounds, due to its ponderous delivery by Nicholas Stuart, like the commentary of a Disney True Life Adventure; the pointless redubbing of Peter O’Toole’s voice; the even more pointless freeze-frame as the final shot — I’d forgotten just how radical it is, a quintessential 60s counterculture movie avant la lettre (as Bob Dylan may have suspected when he wrote “Quinn the Eskimo” later in that decade). It wouldn’t even be accurate to call it an indictment of Western civilization; an indictment of civilization tout court would come closer to the mark.

***

Whenever I lament the absence of any film record of the stage productions of Orson Welles (apart from the closing minutes of his Voodoo Macbeth) or John Cassavates, I should forcibly remind myself of the results of Shirley Clarke’s 1961 film of The Living Theatre’s 1959 stage production of Jack Gelber’s The Connection, a play about junkies, just out on a multiregional DVD from EforFilms, the same Spanish company that released The Greatest Jazz Films Ever (discussed in my Fall 2004 column). It’s possible that I’m unqualified to judge these results because, at the tender age of 16, having been spurred by Robert Brustein’s review, I attended that stage production, directed by Judith Malina, and it remains the most electrifying theatergoing experience in my life — a staged confrontation with the audience that had me reeling. There was no curtain — the junkies were already seated onstage when I entered the auditorium — and I couldn’t even escape the play’s corrosive challenge to my nerves and biases during the intermission, when one of the actors/junkies came into the lobby to beg money from me and other audience members for a fix. How could anyone adapt the equivalent of that cinematically?

I saw the play two more times during its lengthy run, though by the time of my third visit, some of the cast had already changed, including the members of the onstage jazz quartet, which was now headed by Cecil Payne (baritone sax) instead of Freddie Redd (composer and pianist) and Jackie McLean (alto sax). Clarke’s film retains much of the original cast, including Redd’s quartet, and some of the ways it’s been adapted are ingenious, if dated in spots. My personal admiration for Clarke also made this DVD an essential purchase, even though her still-unavailable subsequent features are usually more highly regarded. But a work as dependent on live performance as Gelber’s can’t really survive on film, and what remains isn’t an adequate substitute, even if it does serve as a rough pointer, marker, and/or aide de mémoire. Basically it’s a pungent period piece and Beat curiosity, a precise contemporary of Shadows, with some great hard bop numbers by the quartet. So understandably the DVD is being targeted at a jazz audience. But inexplicably and infuriatingly, the chapter headings, when they refer to those numbers, land one somewhere in the middle of each of them, making it impossible to enjoy the music integrally without a lot of laborious back-pedaling. Maybe the DVD company’s deliberately fucking with my head the way that The Living Theatre once did, but somehow I doubt it.

***

Luis Buñuel made two substantial English-language Mexican features — the highly prestigious Robinson Crusoe (1952) and the totally unprestigious The Young One (1960) — and it’s great that both are out now in decent DVDs. The first, released by VCI Entertainment in the U.S., has been restored and includes an interesting audio interview with Dan O’Herlihy, the lead actor. The second — which boasts no restoration, but still looks fine — is released by Manga Films in Mexico under its Spanish title, La Joven, a Region 2 PAL item with optional Spanish subtitles (or dubbed Spanish dialogue, if that’s your trip). What’s anomalous here is that The Young One, the more interesting work, is Buñuel’s only film set in the U.S. (not counting the brief epilogue of Simon of the Desert) — a wry comic parable of the Deep South, believable and authentic, involving sex, race, and religion. It recalls certain elements in both Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and several William Faulkner novels while remaining a deeply personal work, yet it persists in being one of the most underappreciated and least known works in the Buñuel canon, especially in the U.S.

Meanwhile, Robert Bresson’s own two hillbilly masterpieces, Au hazard Balthazar (1966) and Mouchette (1967), both set in the backwoods of rural France, have been issued on beautifully restored, letterboxed, and subtitled DVDs from Nouveaux Pictures in the U.K. that can’t be recommended too highly. (The same label has done a similarly fine job with Luchino Visconti’s underrated final feature in ‘Scope, L’innocente, which might be described as his most erotic film for heterosexuals, released a decade after Balthazar.) And, in a much pulpier realm, Phil Karlson’s corrosive southern-sleaze noir thriller, The Phenix City Story (1955), complete with its rarely seen documentary prologue, can be found in an acceptable pirated version from Shocking Videos (www.revengeismydestiny.com).

***

Ever since Criterion’s By Brakhage: an anthology, winner of Masters of Cinema’s 2003 DVD of the Year Award, amply demonstrated that experimental films could survive and flourish in that format, I’ve been waiting with bated breath for further demonstrations. (For starters, Michael Snow’s *Corpus Callosum sounds like an obvious choice.) But experimental films tend to occupy a different time frame from commercial and art movies, especially when it comes to distribution, and subsequent blockbusters in this realm have been relatively scattered and unheralded. The following checklist represents a first stab at rectifying this neglect.

Zeitgiest’s DVD of Martina Kudláček’s superb In the Mirror of Maya Deren (2003), the best documentary about an experimental filmmaker that I know, also includes Stan Brakhage’s hand-painted Water for Maya (2000), outtakes from Deren’s lost Witch’s Cradle (1943), and Deren’s choreographic Ensemble for Somnambulists (1951). And if all this whets your appetite for complete Deren films, www.superhappyfun.com is offering her most famous half-dozen shorts. I haven’t yet checked out this collection, but this company’s usual standards — in contrast to those of, say, www.5minutestolive.com, whose DVDs often have a tendency to jam even when the print sources are worth watching — are sufficiently high to make this a fairly safe bet.

Among the other cultish sources, Shocking Videos (see above) seems to have the largest catalog of experimental items, including stuff on DVD-Rs by Peggy Awesh, the Kuchar brothers, Curt McDowell, and Yoko Ono, plus Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s Letter to Jane and even an unsubtitled version of Maurice Lemaître’s 1951 Le film est déjà commence.

Raro Video — the same Italian firm that issued The Chelsea Girls on Region 0 PAL discs (which I discussed three issues back) — now has matching sets of four silent Warhol films from the mid-60s (Kiss, Blow Job, Mario Banana, and a one-hour, 24-frames-per-second Empire) on Region 2 PAL and one with Vinyl (1965) and The Velvet Underground and Nico (1966) on Region 0 PAL. Both sets have bilingual booklets and are too pricey (at least at www.xploitedcinema.com’s prices) for me to check them out, but they certainly sound like they’re worth having.

Finally, The Other Cinema Digital Project (www.othercinemadvd.com) now boasts seven titles, including Johan Grimonprez’s Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, Craig Baldwin’s Spectres of the Spectrum, a limited edition of Bill Morrison’s Decasia, and two interesting collections — The Subject is Sex, a found-footage assembly curated by Stephen Parr, and Experiments in Terror: Abstract and Experimental Horror, which includes a particular favorite, Peter Tscherkassky’s Outer Space.