From the September 27, 1996 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Nina Menkes

With Tinka Menkes, Russ Little, Sherry Sibley, Robert Mueller, and Jack O’Hara.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

For several weeks I’ve been arguing with myself about The Bloody Child, the fourth film and third feature of Nina Menkes — a maddening, obsessive minimalist movie that fails to satisfy me but refuses to leave me alone. This deeply threatening American experimental feature, which has yet to find a distributor, is getting its first extended run anywhere at Facets Multimedia Center this week. Facets recently brought out on video all of Menkes’s previous films — The Great Sadness of Zohara (1984), Magdalena Viraga (1987), and Queen of Diamonds (1991) — and I’ve been seeing and reseeing them as well, mainly because I can’t decide what to do with them either. “For me,” the director has said, “cinema is sorcery,” and there’s little doubt in my mind that all of her work — the worst as well as the best — casts a spell.

All four films star Menkes’s sister Tinka, who’s also credited as coconceiver and coeditor (there are no writing credits on any of them); Nina is credited as producer, cinematographer, director, coconceiver, and coeditor. As sisterly collaborations, these works, to the best of my knowledge, have no parallel in movies. Tinka Menkes plays different characters in each movie — a Jewish girl who leaves Israel for Morocco in The Great Sadness of Zohara, a schizophrenic prostitute who murders her pimp in Magdalena Viraga, a Las Vegas blackjack dealer in Queen of Diamonds (my favorite Menkes film), and a marine captain in California as well as various undefined characters (or guises of the same undefined character) in northeast Africa in The Bloody Child — and in all of these parts she seems to figure to some degree as her sister’s surrogate or alter ego, making her way through a male-dominated universe. All these films, to varying extents, are feminist documents about pain, and part of my quarrel with them — and with myself — is their tendency to exalt certain aspects of female suffering.

I have a similar problem with Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, which is undoubtedly one of the greatest films ever made. The fact that Dreyer was — and that I am — male may complicate this issue. But it remains a problem, whatever the gender of the director or spectator, and whether the acts of creation and viewing are sadism or masochism. Still, there are times when I feel that I’d have to be a woman to respond adequately to what the Menkes sisters are doing.

I don’t have this problem with Chantal Akerman, who may be the minimalist-feminist filmmaker Menkes has learned the most from. What I like least about Magdalena Viraga, my least favorite Menkes production — protracted sequences lingering over the heroine’s bored, alienated expressions while she’s having sex — seems inspired more by Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman than by the way actual prostitutes (or their customers) behave. But in Jeanne Dielman this conceit is necessary if the film is to show its heroine’s ordered life coming apart after she unexpectedly attains an orgasm (as Akerman herself has suggested); in Magdalena Viraga the conceit seems to figure mainly as a mannered rhetorical trope.

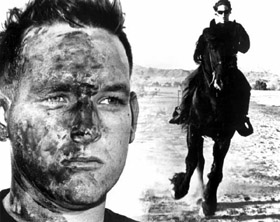

The Bloody Child was inspired by a real incident reported in the Los Angeles Times: a young U.S. marine, recently back from fighting in the gulf war, murdered his wife and was caught trying to bury her in the Mojave Desert by two military policemen on patrol. The arresting officer in the film is the marine captain played by Tinka Menkes, but The Bloody Child doesn’t proceed like a crime story in any ordinary sense; the focus is on the arrest rather than on the crime, which is never shown. We’re also taken into the lives of the captain and other soldiers in the area (29 Palms, the site of the largest U.S. marine base), but not into the life or mind or motivations of the murderer, who’s never heard and is seen only from behind or from a distance. The disembodied voice of the murdered wife is heard periodically (much of what she says comes from Shakespeare’s Macbeth), but she never figures as a character in any ordinary sense — merely as what the production notes describe as a “violated spirit.” In other words, she’s mythologized, along with her husband’s crime, while the husband himself remains unknowable.

Most of the film is about endless waiting: the marine patrol in the Mojave Desert waiting for backup, the spectator waiting for some narrative payoff. It might be said that violence pervades and inflects everything we see and hear in the film, but violence in the usual Hollywood sense is neither seen nor heard. What the movie offers, quite simply, is a vision of hell that corresponds quite closely to American life today, so you may come away from it deciding that, far from being a must-see — as my three-star rating implies — it’s a must-not-see.

The opening shot — of the desert at early dawn, with pink and lavender clouds hanging over mountain peaks and with barely discernible human figures moving across the lower portion of the screen — is incredibly beautiful. This shot is broken up briefly by two opening titles (“a film by Nina Menkes,” “with Tinka Menkes”) and a shot of Tinka in a shawl passing through a gate (in daylight, on another continent), but we’re allowed to linger for so long over this stunning landscape that you start to wonder if your eyes are gradually adjusting to the dark or if it’s the dawn gradually breaking that defines the figures more and more. Yet like so much else in the film, moving toward definition is not the same as arriving there.

Eventually the film’s title — in an arcane script, with the l in Bloody resembling a vine-covered tree — appears over this haunting desert landscape. Then, as if to rhyme with Tinka’s passing through the gate, the film cuts to a shot of the camera moving through an African forest while we begin to hear fragments of the witches’ chants in Macbeth. We return to the desert at dawn, then shift to another part of the desert in daytime — where a parked car is guarded by a soldier — then to a close-up of bloody hands on a corpse inside the car, then to soldiers chatting in a bar, then to a shot behind a soldier driving through the desert, then a return to the parked car and soldier, then a return to the bar. Eventually we return to the African forest, where we find Tinka sitting naked and dirty in a small clearing, writing indecipherable words on her arm.

Much of the film proceeds in this scrambled, patchwork fashion, moving ceaselessly between realism (the desert and bar) and poetry or myth (the forest and Macbeth) — until a beautiful black horse trots improbably through the desert landscape where the cars and soldiers are waiting for backup. Then the distinctness of these separate registers starts to blur. I should add that, with the exception of Tinka Menkes, all the actors in the film were active marines and veterans of Desert Storm, and the realism of their dialogue — most of which they wrote or improvised themselves — puts most Hollywood filmmaking to shame. (Set this film alongside Courage Under Fire, which also deals with the gulf war and a female officer, and the Hollywood “think” piece comes apart like wet Kleenex.) The same virtue is apparent throughout the wonderful Queen of Diamonds and includes the characters’ small talk as well as their more dramatic exchanges. (Interestingly enough, Nina Menkes teaches film production at the University of Southern California, and in spite of her own defiant and extreme anti-Hollywood positions, she’s said to be one of the most popular teachers in that department.)

The footage shot in 29 Palms, constituting most of the film, is all in 35-millimeter; the footage shot in Africa — done much earlier, long before the concept for the remainder of the film crystallized — is blown up from 16-millimeter. This creates a marked difference in visual texture, and I can’t say that the African footage — some of which dimly recalls The Great Sadness of Zohara — does much to enhance the film. The same goes for the offscreen fragments of Macbeth, which seem to serve as a form of artificial respiration for the central narrative and its thematic and semantic gaps — or at least to inject poetry into a fractured, achronological narrative whose integrity depends in great measure on strategic absences. Because I respect the film’s refusal to explain the inexplicable when it comes to depicting a real-life incident, I mistrust its efforts to import poetry from other places and cultures to paper over the resulting holes. (For similar reasons I regret the injections of passages from Gertrude Stein in Magdalena Viraga, though I revere many of those passages in their own right.) We need those holes to realize where we are in a rocky terrain; Macbeth seems more indicative of where we have been, the African footage indicative only of where the Menkes sisters once were.

Still, I can’t deny that The Bloody Child, which is subtitled An Interior of Violence, taps into something central and irreducible about the pervasive role of violence in contemporary American culture that no other picture gets at — something at once chilling and clarifying, and only purified by the movie’s compulsive, purposeful repetitions. Because the Menkes sisters seem to be more intuitive than schematic in the way they work — even when it comes to something as schematic as playing the climactic arrest of the murderer in backward sequence — they’ve allowed us to look into an abyss. It’s only when they try to fill that abyss with Shakespeare and Africa that its power is diminished.